Occurrence of Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary) in Major Potato Growing Areas of Punjab, Pakistan

Occurrence of Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary) in Major Potato Growing Areas of Punjab, Pakistan

Waqas Raza*, Muhammad Usman Ghazanfar and Muhammad Imran Hamid

Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, University of Sargodha, 40100, Sargodha, Pakistan.

Abstract | A survey on the incidence and severity of late blight (Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary) of potato was conducted in the major potato growing areas of Punjab viz., Khushab, Sargodha, Sahiwal, Okara, Jhang and Chiniot districts during the cropping seasons of 2016-2017. A total of six districts comprising of three locations in each district were surveyed for the collection of late blight infected samples. During 2016 and 2017, prevalence of disease in all the surveyed districts ranging between 34.6-24.4% and 39.3-28.6% respectively with district Okara recording the maximum (39.3%) and district Jhang the minimum incidence (24.4%) for both the years. Similarly, disease severity ranging from 19.3-16.1% and 21.1-17.4% during the year 2016 and 2017 was recorded with Okara recording the maximum (21.1%) and Sahiwal the lowest blight severity (16.1%). The results clearly depicted that this disease is present in all the surveyed districts of the Punjab during both years with varying intensities. Moreover, disease incidence and severity seems to be varied from region to region and location to location depending on the prevailing environmental conditions, soil type, prevailing of different mating types and the vulnerability of the crop under plantation.

Received | June 25, 2018; Accepted | July 03, 2019; Published | July 22, 2019

*Correspondence | Waqas Raza, Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, University of Sargodha, 40100, Sargodha, Pakistan; Email: waqasraza61@yahoo.com

Citation | Raza, W., M.U. Ghazanfar and M.I. Hamid. 2019. Occurrence of late blight (Phytophthora infestans (Mont) De Bary) in major potato growing areas of Punjab, Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 35(3): 806-815.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2019/35.3.806.815

Keywords | Survey, Severity, Incidence, Pathogen, Disease, Late blight

Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is one of the fourth most significant food crop across the world after wheat, rice and corn (Nowicki et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2016). In Pakistan, the majority of the people consume less than one tuber a day while in Europe and other part of the world like South America; potato crop is more significant than cereals consumed as a staple food (Haq et al., 2008).

Potato is grown in varied climatic conditions throughout the world as an important part of global food supply (Fry, 2008). Potato is grown over an area of 174.4 thousand hectares in Pakistan with a total production of 3802.3 thousand tons and the average yield was recorded 22 tons per hectares (GOP, 2016). Many biotic factors resulted in low yield of potato crop, among them late blight of potato which caused by P. infestans is very destructive disease (Haq et al., 2008; Rahman et al., 2008; Fry, 2008; Majeed et al., 2017). This disease in 1840s held responsible for the Irish famine that resulted in approximately one million people deaths. Annually, yield losses in the past and still a primary threat to potato crop in Pakistan which leads towards between 30-75% (Haverkort et al., 2009; Ahmed et al., 2015).

One billion of people worldwide are dependent on potato consumption which highlights its popularity and importance to human being (Anwar et al., 2015). The annual cost for controlling this disease is approximated to be more than billions of dollars worldwide (Haverkort et al., 2008). This fungus usually attacks on leaves, stems, petioles when the temperature range from 18-20 ºC and 90-95 % relative humidity which resulted in spread of the disease (Fry, 2008, Tian et al., 2016). The prevalence of the pathogen, P. infestans in district Sawat, Pakistan was firstly reported by Khan et al. (1985). Yield losses inflicted by this disease in the past as well as in present situation made this disease as potential threat to sustainable production of potato in Pakistan (Ahmed et al., 2015). Many alternate hosts such as tomato, volunteer potato plants and potato refuse/cull piles are major source of spread within and across the area. Aerial dispersal, human activity and movement of the pathogen in the soil are a major mechanism for dissemination (Ristaino, 2000).

Disease assessment is one of the most difficult tasks when operating with plant diseases. A plant after attack of disease can be easily recognized on the basis of symptom and sign. Since establishing the status and the resultant yield losses of the disease are pre-requisite for deciding at the logical components of decision making in the adoption of integrated disease management. Current study about the prevalence and severity of disease i.e. two years’ study is the first time study in Punjab, Pakistan according to best information to predict late blight of potato. All the surveys contain fairly large data set and satisfactory results have been achieved regarding potato blight predictions in response to disease. Therefore, the objective of study was to monitor the disease assessment (incidence and severity) in different districts of Punjab, Pakistan.

Materials and Methods

Survey for assessment of late blight disease was conducted in the major growing areas of potato in Punjab (Figure 1) viz., Khushab, Sargodha, Sahiwal, Okara, Jhang and Chiniot during the cropping seasons of 2016 and 2017 (Table 1).

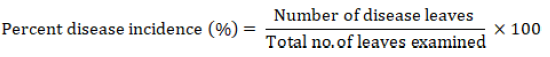

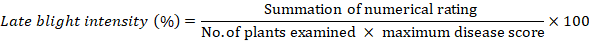

Each district was represented by three locations and each location was further divided into three sites. Five plants were randomly selected from four corners and center of the plot representing each site. Plant diseased samples were collected in the polythene bags from the fields and stores, and brought to the laboratory for further processing. All the leaves were examined for recording incidence of disease and disease incidence was worked out as formula given by James (1974):

Disease severity

The disease severity was measured by randomly marking an area of 1m×1.5m at different places in the field and the observation on the extent of the foliage blighted was recorded by using the disease rating scale by Mohan and Thind (1999).

The disease severity was calculated by using the following formula:

| Disease | Score description in terms of foliar infected (%) |

| Score | No visible symptoms |

| 1 | 1-10 |

| 2 | 11-25 |

| 3 | 26-50 |

| 4 | 51-75 |

| 5 | >75 |

Results and Discussion

Late blight was first identified after visual observing the disease symptoms under field conditions. The earliest symptoms are present in lower leaves consist of small dark green spots that modify from brown to black lesions typically “V” shaped (Hannukkala et al., 2007; Fry, 2008) taken from the potato field during survey Figure 2 (B).

Disease assessment of late blight of potato

Disease incidence: Surveys for disease incidence were conducted in potato growing areas of the Punjab includes Khushab, Sargodha, Sahiwal, Okara, Jhang and Chiniot districts during the year 2016-17 to assess the actual position of late blight occurrence.

The data presented in Figure 3 (A-F) revealed that the prevalence of disease in both the years from all the surveyed locations with varying degrees of mean incidence. Fields in district Okara exhibited the maximum mean blight incidence (36.95%) followed by Sargodha (36.6%), Sahiwal (35%), Khushab (30.2%), Chiniot (28.4%) while least incidence was recorded in the fields of Jhang (26.5%) during 2016 and 17.

The data recorded during the year 2016 season revealed that the occurrence of late blight in all the districts with disease incidence ranging between 34.6-24.4% while Okara district showed maximum disease incidence (34.6%) followed by Sargodha (34.4%), Sahiwal (32.5%), Khushab (29.3%), Chiniot (26.2%) and lowest was observed in Jhang (24.4%). In 2017, same pattern of incidence in all the fields were observed where once again Okara district showed maximum disease incidence (39.3%) followed by Sargodha (38.8%), Sahiwal (37.5%), Khushab (31.1%), Chiniot (30.6) while least incidence (28.6%) was recorded from district Jhnag. Overall, district Okara recorded the maximum disease incidence for both the years may be due to optimum conditions for the survival and spread of the blight pathogen. The site which exhibited late blight incidence of more than 50% was Saleem kot in Sahiwal district. However, all the surveyed fields from different districts viz., Bhawana from district Chiniot exhibited the lowest blight incidence (17%) only (Table 2).

Disease severity: Surveys for disease severity were also conducted in potato growing regions of the Punjab during the 2016-17. The overall data revealed varying degrees of blight severity throughout the potato growing district of the Punjab. The mean disease severity of late blight of potato recorded from different districts for both the years observed that Chiniot district showed highest disease severity (20.2%) followed by Okara, Sargodha, Khushab and Jhang (19.6%, 18.8%, 17.1%, 16.8%) respectively while Sahiwal district showed least severity of 16.75% Figure 4 (A-F) In case of potato late blight severity is concerned for the year 2016, the results revealed that fields in district Okara exhibited the maximum late blight severity (19.3%) followed by those in Chiniot (18.8%), whereas, Sargodha, Khushab and Jhang fields displayed disease severity in the range of 18.2- 16.2%. The data recorded during season of potato growing districts for the year 2017, clearly showed that severity of late blight in all the surveyed districts with the blight severity ranged from 21.1% to 17.4% with same order of districts as were observed in last year of field surveys (Table 3). The late blight unit accumulations shifted within the growing areas for each country, which could result in potato production as some areas experience increased late blight severity, and others experience the decreased late blight severity.

The tuber yield has been decreased almost 3.2 % with compared to last growing season as reported by Ministry of Finance, Pakistan 2016-17. During our two consecutive year surveys (2016-17). We also observed that yield was decreased in the year 2017 as compared to last year might be due to adaptation of the pathogen to environment. We observed lowest tuber mean yield of about 6.7 tons/acre in 2017 which was 7.8 tons/acre in 2016 which is reduced due to increase in disease severity and favorable environmental conditions in Khushab, Sargodha, Sahiwal, Chiniot, Okara and Jhang (10.30 to 7.94, 9.11 to 8.48, 9.24-8.42, 10.22 to 9.60 and 11.81 to 11.71 tons per acre) respectively (Figure 5). The increase in disease severity is indirectly proportional to tuber yield and the same trend has been observed in all the surveyed areas (Figure 4).

Assessment of plant diseases are vital to our interpretation which leads towards management practices (Campbell and Neher, 1994). Potato crop is known to suffer from various diseases caused by various biotic factors like fungi, bacteria, viruses and plant nematodes. Among them, oomycete potato late blight (P. infestans) is commonly occurring disease in field as well as during transit and storage (Horsfield et al., 2010; Peerzada et al., 2013).

Survey of different potato growing area was conducted to monitor the disease assessment caused by the disease in the field. The data recorded during season of potato growing districts clearly showed that occurrence of late blight in all the districts with the blight incidence ranging from 34.6 to 24.4%% for the year 2016 while 39.3-28.6% in case of 2017. For both the years, Okara district showed highest late blight incidence (39.3%) while Jhang was ranked as lowest (24.4%).

Table 1: Areas visited in order to record the incidence and severity of late blight of potato.

| Sr no. | Districts | Locations | Coordinates |

| 1 | Khushab | Khushab, Naushehra (Soon valley), Jauharabad |

32°17′55″N 72°21′3″E |

| 2 | Sargodha | Sargodha ,Shahpur, Sahiwal, |

32°5′1″N 72°40′16″E |

| 3 | Sahiwal | Chak Jeevan Shah, Saleem Kot, Chak Sundhey Khan |

30°39′40″N 73°6′30″E |

| 4 | Okara | Okara, Renala Khurd, Deepalpur |

30°48′33″N 73°27′13″E |

| 5 | Chiniot | Chiniot, Bhawana, Laliyan |

31°43′10″N 72°59′3″E |

| 6 | Jhang | Jhang, Shorkot, Ahmad Pur Sial |

31°16′10″N 72°18′58″E |

The disease severity data reveals varying degrees of blight severity throughout the Punjab. The data recorded during potato growing season in all districts clearly showed that blight severity ranged from 19.3 to 16.1% for the year 2016 while 21.1-17.4% in 2017 field visits.

The disease incidence and severity also observed increasing with advancement in crop growth phase and the light difference of incidence of disease in different locations with respect to their districts might be due to different dates of observations as observed by Fahim et al. (2003).

Almost similar trends of blight severity in potato fields located in different districts of Kashmir were observed during 2008 cropping seasons (Peerzada et al., 2013). The role of environmental factors in the development of potato late blight disease epidemic has been documented (Fahim et al., 2003). The results clearly depicted that this disease is present in all the districts of the Punjab with varying intensities. Incidence has been increased with the passage of time. It is assumed that the disease assessment is more in the areas where potato was cultivated after the harvesting of rice like Okara, Sahiwal, Sargodha which might be due to the damp condition and presence of more moisture in the soil which favors rapid development of the disease. Incidence of the disease is increasing and if it remains unattended, it can occur in epidemic form and destroy the potato crop in the years to come (Rotem, 2012; Peerzada et al., 2013).

The yield losses were reported up to 50- 70% (Haq et al., 2008) while Kumar et al. (2003), Fry (2008), Dowley et al. (2008) and Thomas-Sharma et al. (2016) reported 25- 85% yield losses due to late blight primarily on the degree of vulnerability of the effected plant. While, more recently Ahmed et al. (2015) observed almost 100% yield losses under favorable environmental conditions in Pakistan. The adoption of different cropping patterns and the use of different varieties in the field also account for such difference in incidence percentage with respect to locations.

Table 2: Disease incidence of potato growing areas of the Punjab, Pakistan.

| District | Location | Site | 2016 | 2017 |

| Khushab | Khushab | Katha Saghral | 33 | 37 |

| Nari | 30 | 31 | ||

| Padhrar | 19 | 20 | ||

| Jauharabad | Mitha Tiwana | 32 | 32 | |

| Chak No.14/Mb | 19 | 21 | ||

| Choha | 30 | 31 | ||

| Noshera | Angah | 38 | 40 | |

| Khabaki | 38 | 42 | ||

| Mardwal | 25 | 26 | ||

| Mean | 29.3 | 31.1 | ||

| Sargodha | Sargodha | Havali Majoka | 19 | 42 |

| Farooka | 38 | 40 | ||

| Thati Sargodha | 30 | 32 | ||

| Shahpur | Shahpur Sadar | 35 | 53 | |

| Aqil Shah | 45 | 32 | ||

| Jalal Pur Jadeed | 42 | 30 | ||

| Sahiwal | Jahanian Shah | 36 | 38 | |

| Chaway Wala | 25 | 47 | ||

| Lakhiwal Sharif | 40 | 36 | ||

| 34.4 | 38.8 | |||

| Sahiwal | Chak Jeevan shah | Ghaziabad | 38 | 44 |

| Gulistan | 28 | 30 | ||

| Iqbal Nagar | 27 | 29 | ||

| Saleem kot | Kassowal | 43 | 46 | |

| Nai-Abadi | 40 | 50 | ||

| Pahri | 34 | 42 | ||

| Chak Sundhey Khan | Sikhanwala | 23 | 26 | |

| Tirathpur | 25 | 34 | ||

| Mirbaz | 35 | 37 | ||

| 32.5 | 37.5 | |||

| Okara | Okara | Bibi Pur | 37 | 21 |

| Fateh Pur | 38 | 46 | ||

| Tariq Abad | 30 | 37 | ||

| Renala khurd | Akhtarabad | 47 | 38 | |

| Bazeeda | 24 | 48 | ||

| Mopalkey | 26 | 44 | ||

| Deepalpur | Qadir Abad | 37 | 38 | |

| Kani Pur | 46 | 37 | ||

| Mazhar Abad | 27 | 45 | ||

| 34.6 | 39.3 | |||

| Chiniot | Chiniot | Salaray | 33 | 36 |

| Tahirabad | 22 | 28 | ||

| Rao Bagg | 24 | 28 | ||

| Bhawana | Jamia Abad | 30 | 32 | |

| Haveli Chadharh | 17 | 20 | ||

| Barana | 28 | 36 | ||

| Lalian | Thatta Musa | 27 | 31 | |

| Tahli Mangeni | 23 | 25 | ||

| Rao Bagh | 30 | 40 | ||

| 26.2 | 30.6 | |||

| Jhang | Jhang | Chellay Wala Thall | 33 | 36 |

| Mandi Shah Jeewna | 26 | 27 | ||

| Mohza Hasnana | 18 | 24 | ||

| Shorkot | Haveli Bahadar Shah | 23 | 25 | |

| Ludah Mahni | 22 | 24 | ||

| Chak no.478/JB | 20 | 31 | ||

| Ahmad Pur Sial | Basti Mian Ahmed Din | 25 | 33 | |

| Pir Abdul Rehman | 27 | 31 | ||

| Hasoo Balel | 26 | 27 | ||

| 24.4 | 28.6 |

Table 3: Disease severity of potato growing areas of the Punjab, Pakistan.

| District | Location | Site | 2016 | 2017 |

|

Khushab |

Khushab |

Mangoor | 15.3 | 15.2 |

| Jalal pur | 16.5 | 17.2 | ||

| Abbas pura | 18.9 | 23.2 | ||

|

Jauharabad |

Mitha Tiwana | 17.3 | 15.2 | |

| Chak No.14/Mb | 15.4 | 17.2 | ||

| Choha | 19.3 | 17.3 | ||

|

Noshera |

Angah | 16.4 | 19.2 | |

| Khabaki | 19.7 | 16.7 | ||

| Mardwal | 10.5 | 18.2 | ||

| Mean | 16.5 | 17.7 | ||

|

Sargodha |

Sargodha |

Havali Majoka | 18.3 | 19.5 |

| Farooka | 16.4 | 18.5 | ||

| Thati Sargodha | 14.2 | 15.3 | ||

|

Shahpur |

Shahpur Sadar | 13.5 | 15.5 | |

| Aqil Shah | 16.7 | 17.7 | ||

| Jalal Pur Jadeed | 19.8 | 20.9 | ||

|

Sahiwal |

Jahanian Shah | 21.4 | 22.5 | |

| Chaway Wala | 28.3 | 29.4 | ||

| Lakhiwal Sharif | 15.4 | 16.5 | ||

| 18.2 | 19.5 | |||

|

Sahiwal |

Chak Jeevan shah | Ghaziabad | 19.4 | 20.5 |

| Gulistan | 15.3 | 17.4 | ||

| Iqbal Nagar | 13.5 | 15.2 | ||

|

Saleem kot |

Kassowal | 14.4 | 15.7 | |

| Nai-Abadi | 16.5 | 17.2 | ||

| Pahri | 11.4 | 12.2 | ||

| Chak Sundhey Khan | Sikhanwala | 18.5 | 19.61 | |

| Tirathpur | 17.4 | 18.41 | ||

| Mirbaz | 19.3 | 20.4 | ||

| 16.1 | 17.4 | |||

|

Okara |

Okara |

Bibi Pur | 18.4 | 19.5 |

| Fateh Pur | 17.3 | 19.7 | ||

| Tariq Abad | 19.4 | 21.3 | ||

|

Renala khurd |

Akhtarabad | 21.2 | 23.2 | |

| Bazeeda | 23.4 | 25.2 | ||

| Mopalkey | 22.3 | 23.4 | ||

|

Deepalpur |

Qadir Abad | 15.3 | 17.2 | |

| Kani Pur | 17.4 | 19.3 | ||

| Mazhar Abad | 19.3 | 21.2 | ||

| 19.3 | 21.1 | |||

|

Chiniot |

Chiniot |

Salaray | 21.4 | 22.5 |

| Tahirabad | 22.5 | 23.7 | ||

| Rao Bagg | 24.3 | 25.4 | ||

|

Bhawana |

Jamia Abad | 15.4 | 17.3 | |

| Haveli Chadharh | 17.2 | 19.2 | ||

| Barana | 15.9 | 17.1 | ||

|

Lalian |

Thatta Musa | 19.3 | 21.2 | |

| Tahli Mangeni | 17.2 | 18.4 | ||

| Rao Bagh | 16.4 | 19.3 | ||

| 18.8 | 20.4 | |||

|

Jhang |

Jhang |

Chellay Wala Thall | 13.4 | 15.7 |

| Mandi Shah Jeewna | 15.3 | 17.5 | ||

| Mohza Hasnana | 21.2 | 19.1 | ||

|

Shorkot |

Haveli Bahadar Shah | 13.2 | 18.4 | |

| Ludah Mahni | 15.4 | 16.3 | ||

| Chak no.478/JB | 17.5 | 19.5 | ||

|

Ahmad Pur Sial |

Basti Mian Ahmed Din | 16.3 | 17.1 | |

| Pir Abdul Rehman | 17.5 | 21.3 | ||

| Hasoo Balel | 16.5 | 12.2 | ||

| 16.2 | 17.4 |

The late blight disease of potato is re-emerging across the world (Fry et al., 2015) therefore; the same disease is frequently studied by various scientists across the world (Subbarao et al., 2015). Similarly, unstable degree of crop losses due to late blight has been recorded by Bhat et al. (2010) in Punjab. It was observed that the disease severity varied from State to State and overall 10-15% yield losses were estimated during 2013-14 due to late blight. The tuber yield of potato with respect to disease prevalence decreases (Lal et al., 2016). It might be due to prevalence of complex race of the pathogen. Peerzada et al., 2013 monitored disease incidence of late blight of potato in Kashmir valley, Pakistan and observed the prevalence of disease with the blight incidence ranged between 39.2% to 49.6%. Both the late blight incidence and severity increased with development in crop growth stage. A survey was conducted to monitor the disease incidence in potato growing areas of Swat valley, Pakistan by Ahmad et al. (2015) revealed that out of 32 potato fields Powdery scab, black scurf, and late blight were the main prevalent diseases of potato. Similarly, Naher et al., 2013 surveyed 150 different fields of Bangladash during potato cropping season 2007-08 to check disease severity and observed that there were a lot of variations in disease in different districts. Our results are almost similar to the findings of Abbas, 2017 who conducted a survey in randomly selected five fields in Nomal Valley of GB and observed the highest percent disease severity 66.4%. Late blight disease incidence ranged between 0 to 85.71% when Naffaa et al., 2017 collected diseased samples from five different regions to examine prevalence of the disease across the interior of Syria during 2011, 2013 and 2014 cropping seasons.

Most of the published studies have showed that meteorological factors suitable for potato late blight development are: temperature, humidity, and rainfall or leaf wetness interval. Temperature ranged between 17 to 22°C and humidity in excess of 90% is observed to favor potato blight development in the areas of sample collection (Modesto et al., 2016). Due to the impact of meteorological factors for blight development in sampled areas of Punjab, weather maps and different forecast models have been used in forecasting potato blight and timing of chemical based applications to manage disease (Olanya et al., 2012 a, b). The environmental variations especially temperature (Erwin and Ribeiro, 1996) throughout the potato growing areas of Punjab also favored pathogen survival. Moreover, during the field surveyed in potato growing areas it has been observed that in the presence of moisture (water) and suitable temperatures (18°C) sporangia germinate, and infection of stem tissues occurs and white mildew can be seen with naked eye (Modesto et al., 2016).

While humidity also have greater impact if the pathogen developed greater tolerance for dry conditions and the requirement for high humidity, a proxy for leaf surface wetness, is common for many foliar pathogens including P. infestans causing late blight disease (Caubel et al., 2012). The requirement for high relative humidity may limit the response to climate change for other foliar pathogens, which would otherwise have experienced temperature as a primary limiting factor.

High precipitation and relative humidity in high disease incidence area like Okara, while, reverse in case of Jhang due to reduced relative humidity (Sunseri et al., 2002). A well understanding of the environmental factors of potato late blight, the purpose of theoretical models to location- specific contexts, and determining the potential for use of weather forecasts are important considerations (Hamill et al., 2006).

In the area under studied, the farmers mainly apply chemicals to overcome this disease that leads towards health hazard and development of fungicide resistance world over including Pakistan, which has necessitated the exercise of additional alternative strategies for the control of disease (Arora et al., 2014). Based on the results of the present study, it is suggested that the farmers should cultivate the resistant varieties like Caroda, apply chemicals when/where need bases and apply alternatives such as botanical and biocontroal agents (Lal et al., 2016; Majeed et al., 2015, 2017).

Conclusions and Recommendations

Disease epidemics are one of the most challenging tasks to study plant diseases. Insight into the data revealed that comparatively more disease incidence and severity in 2017 as compared to that in 2016 all the surveyed locations, may be due to fluctuation in environmental factors. Trials about disease risk analyses based on host–pathogen interactions should be planned, and research on host response should be conducted to understand how change in the climatic conditions could affect the progress of late blight diseases.

Future strategies

Applying climate changes in future the current scenarios of potato cropping systems indicated small global tuber yield of potato reductions by 2055 (−2% to −6%), but larger declines by 2085 (−2% to −26%), depending on the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP). The simulated impacts varied depending on the potato growing areas, with high tuber reductions in the high latitudes and the lowlands of different countries, but less so in the mid-latitudes and tropical highland. Ambiguity due to different climate models were also similar to seasonal variability by mid-century, but became larger than year-to-year variability by the end of the century.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to the support provided by Higher Education Commission, Islamabad, Pakistan for funding the project (204448/NRPU/R and D/HEC/14/1074) for Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, University of Sargodha, Sargodha.

Novelty Statement

The assessment of potato late blight disease is inadequately documented in Pakistan in different potato growing zones. Keeping in mind, field surveys were conducted to draw exact picture of pathogen for its effec-tive management strategies with respect to disease sampled fields.

Author’s Contribution

Muhammad Usman Ghazanfar and Imran Hamid conceived the idea, facilitated, guided and supervised the surveys while Waqas Raza executed the field visits, took experimental data, wrote and finalized the manuscript.

References

Abbas, A. 2017. First report of alternaria blight of potatoes in Nomal valley, Gilgit-Baltistan Pakistan. Appl. Microbiol. 1 (3): 2471-9315. https://doi.org/10.4172/2471-9315.1000137

Ahmad, I. and J. I. Mirza. 1995. Occurrence of A2 mating type of Phytophthora infestans in Pakistan. In research and development of potato production in Pakistan. Proc. Nat. Seminar held at NARC, Islamabad. Pak. 23-25 April, 1995. pp. 189-196.

Ahmad, M., M.U. Afzal, M.K. Afzal, A.R. Khan and N. Javeed. 2015. Screening of potato germplasm and evaluation of fungicides against late blight of potato. Myco. Pathol. 12(2).

Ahmed, N., A. Khan, A. Khan and A. Ali. 2015. Prediction of potato late blight disease based upon environmental factors in Faisalabad, Pakistan. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. S3: 008. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7471.1000S3-008

Anwar, D., D. Shabbir, M.H. Shahid and W. Samreen. 2015. Determinants of potato prices and its forecasting: A case study of Punjab, Pakistan. Univ. Libr. Munich, Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/66678.

Arora, R.K. 2009. Late blight, an increasing threat to seed potato production in the north-western plains of India. Acta. Hortic. (ISHS) 834: 201-204. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.834.22

Bessadat, N., S. Benichou, M. Kihal and D.E. Henni. 2014. Aggressiveness and morphological variability of small spore. J. Exp. Biol. 2: 2320-8694.

Bhat, N.M., B.P. Singh, R.K. Arora, R.P. Rai, I.D. Garg and S.P. Trehan. 2010. Assessment of crop losses in potato due to late blight disease during 2006-2007. Potato J. 37: 37-43.

Campbell, C.L. and D.A. Neher. 1994. Estimating disease severity and incidence. Epidemiol. Manage. Root Dis. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 117-147. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-85063-9_5

Caubel, J., M. Launay, C. Lannou and N. Brisson. 2012. Generic response functions to simulate climate based processes in models for the development of airborne fungal crop pathogens. Ecol. Modell. 242: 92-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.05.012

Erwin, D.C and O.K. Ribeiro. 1996. Phytophthora diseases worldwide. Am. Phytopathol. Soc. (APS Press).

Fahim, M.A., M.K. Hassanien and M.H. Mostafa. 2003. Relationships between climatic conditions and Potato Late Blight epidemic in Egypt during winter seasons 1999–2001. Appl. Ecol. Env. Res. 1(1-2): 159-172. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/01159172

Forbes, G.A., N.J. Grünwald, E.S.G. Mizubuti, J.L. Andrade-Piedra and K.A. Garrett. 2007. Potato late blight in developing countries. Peters, R.(ed.) Curr. Concepts Potato Dis. Manage. Kerala, India: Res. Signpost. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/67295

Fry, W. 2008. Phytophthora infestans: the plant and R gene destroyer. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9(3): 385-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00465.x

Fry, W.E., P.R.J. Birch, H.S. Judelson, N.J. Grünwald, G. Danies, K.L. Everts and M.T. McGrath. 2015. Five reasons to consider Phytophthora infestans a re-emerging pathogen. Phytopathol. 105(7): 966-981. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-01-15-0005-FI

Hamill, T.M., J.S. Whitaker and S.L. Mullen. 2006. Reforecast: An important dataset for improving weather predictions. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87(1): 33-46. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-87-1-33

Hannukkala, A.O., T. Kaukoranta, A. Lehtinen and A. Rahkonen. 2007. Late‐blight epidemics on potato in Finland, 1933–2002; increased and earlier occurrence of epidemics associated with climate change and lack of rotation. Plant Pathol. 56(1): 167-176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2006.01451.x

Haverkort, A.J., P.C. Struik, R.G.F. Visser and E. Jacobsen. 2009. Applied biotechnology to combat late blight in potato caused by Phytophthora infestans. Potato Res. 52: 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-009-9136-3

Haverkort, A.J., P.M. Boonekamp, R. Hutten, E. Jacobsen, L.A.P. Lotz, G.J.T. Kessel and E.A.G. Van der Vossen. 2008. Societal costs of late blight in potato and prospects of durable resistance through cisgenic modification. Potato Res. 51(1): 47-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-008-9089-y

Horsfield, A., T. Wicks, K. Davies, D. Wilson and S. Paton. 2010. Effect of fungicide use strategies on the control of early blight (Alternaria solani) and potato yield. Aust. Plant Pathol. 39(4): 368-375. https://doi.org/10.1071/AP09090

James, W.C. 1974. Assessment of plant diseases and losses. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 12(1): 27 48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.py.12.090174.000331

Kumar, S., P.H. Singh, I.D. Garg and S.M.P. Khurana. 2003. Integrated management of potato diseases. Indian Horticul. 48(2): 25-27

Lal, M., R.K. Arora, U. Maheshwari, S. Rawal and S. Yadav. 2016. Impact of late blight occurrence on potato productivity during 2013-14. Int. J. Agric. Stat. Sci. 12(1): 187-192.

Li, Y., D.E. Cooke, E. Jacobsen and T. van der Lee. 2013. Efficient multiplex simple sequence repeat genotyping of the oomycete plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans. J. Microbiol. Methods. 92(3): 316-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.021

Majeed, A., Z. Chaudhry, I. Haq, Z. Muhammad and H. Rasheed. 2015. Effect of aqueous leaf and bark extracts of Azadirachta indica A. Juss, Eucalyptus citriodora Hook and Pinus roxburghii Sarg. on late blight of potato. Pak. J. Phytopathol. 27(1): 15-20.

Majeed, A., Z. Muhammad, R. Ullah, H. Ullah and H. Ahmad. 2017. Late blight of potato (Phytophthora infestans) I: Fungicides application and associated challenges. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 5(3): 261-266. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v5i3.261-266.1038

Mehi L., S. Sharma, S. Yadav and S. Kumar. 2018. Management of late blight of potato, potato - from incas to all over the world, Mustafa Yildiz, Intech. Open.

Modesto, O.O., M. Anwar, Z. He, R.P. Larkin and C.W. Honeycutt. 2016. Survival potential of Phytophthora infestans sporangia in relation to environmental factors and late blight occurrence. J. Plant Prot. Res. 56(1): 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1515/jppr-2016-0011

Naffaa, W., S. Ibrahim, T.A. Alfadil and A. Al-Daoude. 2017. Incidence of the potato late blight pathogen, Phytophthora infestans in Syria and its mating type. J. Plant Dis. Protect. 124(6): 533-537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-017-0130-8

Naher, N., M. Hossain and M.A. Bashar. 2013. Survey on the incidence and severity of common scab of potato in Bangladesh. J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh. 39(1): 35-41. https://doi.org/10.3329/jasbs.v39i1.16031

Nowicki, M., E.U. Kozik and M.R. Foolad. 2013. Late blight of tomato in R.K. Varshney and R. Tuberosa (ed.). Translational genomics for crop breeding. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. An Introduction pp. 241- 265. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118728475.ch13

Olanya, O.M., C.W. Honeycutt, B. Tschöepe, B. Kleinhenz, D.H. Lambert and S.B. Johnson. 2012b. Effectiveness of simblight1 and simphyt1 models for predicting Phytophthora infestans in north-eastern United States. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Protect. 45(13): 1558-1569. https://doi.org/10.1080/03235408.2012.681502

Olanya, O.M., C.W. Honeycutt, Z. He, R.P. Larkin, J.M. Halloran and J.M. Frantz. 2012a. Early and late blight potential on russet Burbank potato as affected by microclimate, cropping systems and irrigation management in northeastern United States. Sustainable Potato Prod. Glob. Case Stud. (pp. 43-60). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4104-1_3

Olanya, O.M., R.P. Larkin and C.W. Honeycutt. 2015. Incidence of Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary on potato and tomato in Maine, 2006–2010. J. Plant. Prot. Res. 55(1): 58-68. https://doi.org/10.1515/jppr-2015-0009

Parvez, E., S. Hussain, A. Rashid and M.Z. Ahmad. 2003. Evaluation of different protectant and eradicant fungicides against early and late blight of potato caused by Alternaria sotaní (Ellis and Mart) jones and grout and Pytophthora infestons (Mont.) de вагу under field conditions. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 6(23): 1942-1944. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2003.1942.1944

Rahman, M.M., T.K. Dey, M.A. Ali, K.M. Khalequzzaman and M.A. Hussain. 2008. Control of late blight disease of potato by using new fungicides. Int. J. Sustain. Crop Prod. 3(2): 10-15.

Ristaino, J.B and M.L. Gumpertz. 2000. New frontiers in the study of dispersal and spatial analysis of epidemics caused by species in the genus Phytophthora. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38(1): 541-576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.38.1.541

Rotem, J. 2012. Climatic and weather influences on epidemics. Plant disease: Adv. Treatise How Dis. Dev. Populations. 317. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-356402-3.50023-2

Subbarao, K.V., G.W. Sundin and S.J. Klosterman. 2015. Focus issue articles on emerging and re-emerging plant diseases. Phytopathol. 105(7): 852-854. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-105-7-0001

Sunseri, M.A., D.A. Johnson and N. Dasgupta. 2002. Survival of detached sporangia of Phytophthora infestans exposed to ambient, relatively dry atmospheric conditions. Am. J. Potato Res. 79(6): 443. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02871689

Thomas‐Sharma, S., A. Abdurahman, S. Ali, J.L. Andrade‐Piedra, S. Bao, A.O. Charkowski and L. Torrance. 2016. Seed degeneration in potato: the need for an integrated seed health strategy to mitigate the problem in developing countries. Plant Pathol. 65(1): 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12439

Tian, Y.E., J.L. Yin, J.P. Sun, Y.F. Ma, Q.H. Wang, J.L. Quan and W.X. Shan. 2016. Population genetic analysis of Phytophthora infestans in northwestern China. Plant Pathol. 65(1): 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12392