Multifactorial Influences on Rabies Antibodies in Moroccan Exported Dogs

Research Article

Multifactorial Influences on Rabies Antibodies in Moroccan Exported Dogs

Saloua Ziani1*, Khalid Sohaib2 , Youssef Lhor3, Ikhlass El Berbri4, And Ouafaa Fassi Fihri4

1Veterinary Service of Rabat, National Food Safety Office, Rabat, Morocco; 2MASAFEQ Laboratory, Department of Economics, National Institute of Statistics and Applied Economics, Rabat, Morocco; 3Régional Direction of Rabat Salé Kenitra, National Food Safety Office, Rabat, Morocco; 4Department of Veterinary Pathology and Public Health, Hassan II Agronomic and Veterinary Institute, Rabat, Morocco.

Abstract | Rabies is a viral zoonosis caused by the Lyssavirus, and dogs are the primary host and reservoir. For the international movement of pets, rabies-free countries require a rabies quantification before importing animals, which varies significantly. The objective of this study is to investigate the reasons for variations in antibody titers in dogs. Data from 848 dogs exported from Morocco was collected. The results revealed that too-old dogs (over six years) or too young (under four months) are also less likely to respond to vaccination than dogs that are four months to six years old. A dog receiving a booster dose is better immunized than a dog receiving a single dose. On the other hand, the time interval between the last vaccination and the time of sampling also affected the titer. The longer the interval, the lower the titer measured, and this effect becomes more pronounced when the interval exceeds 60 days. The sex did not appear to affect the rabies antibody titer. Many factors influence the antibody titer of rabies. Thus, a double primary vaccination is strongly recommended in a rabies-endemic country like Morocco.

Keywords | Antibody titers, Dog, Factors, Rabies, Vaccination

Received | April 14, 2023; Accepted | May 25, 2023; Published | September 15, 2023

*Correspondence | Saloua Ziani, Veterinary Service of Rabat, National Food Safety Office, Rabat, Morocco; Email: saloua.ziani@onssa.gov.ma

Citation | Ziani S, Sohaib K, Lhor Y, El Berbri I, Fihri AOF (2023). Multifactorial influences on rabies antibodies in moroccan exported dogs. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 11(10): 1744-1750.

DOI | https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.aavs/2023/11.10.1744.1750

ISSN (Online) | 2307-8316

Copyright: 2023 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

INTRODUCTION

Rabies is a viral zoonoses caused by viruses belonging to the order: Mononegavirales, family: Rhabdoviridae, and the genus: Lyssavirus genus. It is responsible for an estimated 59,000 human deaths yearly, with 36.4% in Africa (Hampson et al., 2015). All mammals are susceptible to infection by the rabies virus (RABV). The dog is the primary host and reservoir of the virus, and 99% of human cases are caused by infected dog bites (WHO, 2018). In Morocco, a yearly average of 384 domestic animal rabies cases were reported from 1986 to 2016, and an average of 22 cases of human rabies were reported yearly (Khayli et al., 2019). The vaccines recommended by WHO and WOAH for rabies control in endemic areas are inactivated cell culture injectable vaccines (WHO, 2018). The vaccination schedule suggested by the Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) is a primary vaccination at 3 months of age with two booster doses 2 to 4 weeks apart, followed by an annual vaccination, and after boosters (one year or more) according to the manufacturer’s indication or local regulations (Day et al., 2016).

To maintain the free status of some countries, WHO and WOAH recommend the anti-rabies vaccination and anti-rabies titration of pets entering their territory. The tests recommended by WOAH and WHO are the FAVN and RFFIT. The minimum required rabies titer is 0.5 IU/ml (WHO, 2018; WOAH, 2018).

Within the framework of international pet movements, the official Moroccan services certified 284 cases of dogs and cats in 2017 (ONSSA, 2018), and this figure is increasing yearly. The veterinary service in Rabat issued an average of 268 dog and cat exportation certificates (2017–2021 period), of which 59% were destined for countries of the European Union and 26% for Canada and the USA (SVR, 2022). The examination results are subjected to many variations. Previous work reported that the ability of the dog to produce an adequate antibody titer after rabies vaccination depends on several factors, including age, breed of the animal, number of vaccine doses received, and the interval between vaccination and serological testing (Mansfield et al., 2004; Zanoni et al., 2010; Kennedy et al., 2007; Berndtsson et al., 2011). We aimed to evaluate the reasons behind these variations based on the data mentioned in the dogs’ vaccination records and test reports. This study is the first of its kind in Morocco.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data and Variables

A total of 848 blood samples were collected and analyzed for international exportation. Data on each animal tested were collected from seven veterinary services responsible for the travel certification of pets (Rabat, Marrakech, Tangier, Casablanca, Agadir, Mohammedia, and Témara).

Data included breed, sex, age, vaccines used, dates of vaccination, date of sampling for titration, antibody titer, and type of test performed. The dataset was evaluated; incorrectly entered records were removed, and only blood samples collected between 2012 and August 2022 were considered.

This study focused on two groups of dogs: the first group (248 dogs, 29%) with a single anti-rabies vaccination, and the second group (600 dogs, 71%) was vaccinated twice.

The rabies vaccines used were approved in Morocco and the countries where they were made. They are inactivated vaccines, either monovalent (66.3%) or polyvalent (33.7%).

According to their age at the primary vaccination, the dogs were classified into four groups: <=4 months, 4: 12 months, 1: 6 years, and > 6 years.

The time from vaccination to rabies titration is expressed in days and has been divided into 5 groups: 3-30, 31-60, 61-90, 90-180, and >180 days. Note that blood samples from dogs receiving a single vaccination were taken 30 days after the rabies vaccination.

Based on information from the site https://www.woopets.fr/recherche/?searchInput=les+races+de+chiens, the dogs have been classified according to their size into three categories: small, medium, and large.

As required by EU pet travel rules, antibody titrations were carried out in labs that had been approved by the EU. Two cell seroneutralization techniques were used: the fluorescent antibody virus neutralization (FAVN) and the rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT). Thus, 69.7% of the samples were analyzed by the FAVN test versus 30.3% by the RFFIT test.

Table 1 presents the variables studied and their adopted specifications.

Methods

Multinomial logistic regression

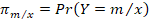

Structural modeling utilizing logistic multinomial regression was used. Multinomial logistic regression is a common type of supervised learning algorithm used for predicting the outcomes of categorical dependent variables with m categories (more than two categories)—in our case, titer groups. This method is similar to linear regression in that it uses predictor variables to estimate the probability of each category for the dependent variable. The basic idea of multinomial logistic regression is that given a set of predictor variables, in our case, sex, age at primary vaccination, time from vaccination to sampling for titer measurement, test performed, dog’s size, and the number of vaccinations, we can estimate the probability of the dependent variable falling into each of its possible categories. The probability of the occurrence of a modality m is expressed in the following conditional form:

We choose a reference event, for instance, M (in our case, the moderate response), and we consider the M-1 logistic regression models in which the other events are regressed compared to the reference (Russolillo, 2018).

Where are the estimated coefficients for each corresponding independent variable in the logistic multinomial regression equation for category k.

What is an odds ratio?

Odds ratios are commonly used measures in logistic regression models, including multinomial logistic regression. They assess the impact of the independent variables on the relative probabilities of the different categories of the dependent variable.

| Variable | Type of variable | Explanation |

| Titer groups | Dependent variable, qualitative of 3 levels |

This refers to the level of titration, according to the following breakdown: Low responses: [0.5IU/ml-3IU/ml] Moderate responses: ]3IU/ml -10IU/ml [ High responses: greater or equal to 10IU/ml |

| Gender | Independent variable, qualitative of 2 levels |

This variable refers to the dog’s sex. Male Female |

|

Age at vaccination

|

Independent variable, qualitative of 4 levels |

This variable corresponds to the age of the dog at the first vaccination. <=4 months; ]4 months ,1 year]; ]1 year ,6 years]; + 6 Years. |

|

Time from vaccination to sampling for titer measurement

|

Independent variable, qualitative of 5 levels

|

This variable refers to the time interval between the day of vaccination and the day of blood collection for titration measurement [3d-30d]; [31d-60d]; [61d-90d]; [90d-180d]; +180d. |

| Test performed | Independent variable, qualitative of 2 levels | This refers to the type of test performed, RFFIT or FAVN. |

| Dog size | Independent variable, qualitative of 3 levels | This variable corresponds to the dog’s size. It can be small, medium, or large, depending on its weight. |

| Groups | Independent variable, qualitative of 2 levels | This variable refers to the number of vaccinations the dog has received; it may be one or two. |

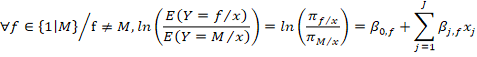

The formulas for calculating odds ratios in the case of logistic multinomial regression are as follows:

Let be the estimated coefficients for each corresponding independent variable in the logistic multinomial regression equation for category k.

The odds ratio measures the ratio of the odds of two different categories to a given reference category. Therefore, we need to choose a reference category, often the last category, M, to compare the other categories.

To compare category m with reference category M, the odds ratio can be calculated as follows:

This implies that the odds ratio is calculated by taking the exponential of the sum of the products of the estimated coefficients and the values of the corresponding independent variables for the category m (Russolillo, 2018).

How to interpret the effect of the predictor variables on the target variable using odds ratios?

In multinomial logistic regression, the odds ratio (OR) is the ratio of the chances that one event will happen compared to the chances that another event will happen.

In multinomial logistic regression, how you understand the odds ratio depends on the rest of the analysis. In general, if the OR is greater than 1, it means that if the independent variable goes up, the response variable is more likely to fall into that category. If the OR is less than 1, on the other hand, it means that if the independent variable goes up, the response variable is less likely to fall into that category.

Tools

All statistical manipulations and outputs are the authors’ production under the R software (UCLA, 2023).

The descriptive analysis was done using Microsoft Excel software.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

Out of 848 dogs, 29.6% had low rabies antibody titers (0.5-3 IU/ml), 39.7% had a moderate titer (3-10 IU/ml), and 30.7% had a high titer (≥ 10 IU/ml).

Females account for 57.4% and males account for 42.6% of the study population. Both sexes have almost the same frequency of occurrence (Figure 1). This leads us to suspect that the sex of the dog does not influence the degree of response to vaccination (Figure 1).

Table 2: Multinomial logistic regression Odds Ratios using Tidy library in R

| Variables'levels | Titer groups. Levels Odds Ratios & P-Value /Ref =Moderate responders | |||

| Low responders | High responders | |||

| Odds Ratios | P-Value | Odds Ratios | P-Value | |

| 1- Sex /Ref=Male | ||||

| Female | 0,98 | >0.9 | 1.03 | 0.8 |

| 2- Age at vaccination/Ref= ]1 Year,6 Years] | ||||

| <=4 months | 1.64** | 0,025 | 1.42 | 0.11 |

|

]4 months ,1 year] |

1.37 | 0.2 | 1.25 | 0.4 |

| 6+ Years | 1.92 | 0.10 | 0,20** | 0,035 |

| 3- Time from vaccination to sampling for titer measurement /Ref= [3d-30d] | ||||

| [31d-60d] | 1.55 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 0.8 |

| [61d-90d] | 2.34** | 0.019 | 0.83 | 0.6 |

| [91d-180d] | 2.69*** | 0.004 | 0.54* | 0.078 |

| + 180d | 2.29** | 0.022 | 0.34*** | 0.006 |

| 4- Test performed/Ref=FAVN | ||||

| RFFIT | 0.65** | 0.033 | 1.67*** | 0.010 |

| 5- Dog Size/Ref=Small | ||||

| Medium | 2.14*** | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.2 |

| Large | 3.00*** | <0.001 | 0.35*** | 0.002 |

| 6- Groups/Ref=One vaccination | ||||

| Two vaccinations | 0.68** | 0.037 | 2.60*** | <0.001 |

|

- Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01, - Ref refers to reference level |

||||

Figure 2 showed that there is a big difference between the dogs that were vaccinated once (VO) or twice (VT).

38.8% of VT had a high titration level compared to 16.7% of VO, 42.86% of VT dogs had a moderate titration level compared to 38.3% of VO, and 26.80% of VT were low-titrated compared to 40.41% of VO. Descriptive analysis showed that VT dogs are more likely to have higher titration levels than VO dogs (Figure 2).

Modeling results

Our model considered the dependent variable is the titer and the predictors are sex, age at vaccination, time from vaccination to sampling for titer measurement, Test performed, and dog size and groups. Odds ratios were calculated out of the structural multinomial logistic regression models using the tidy library in the R language (Github, 2023) (Table 2) (Figure 4).

Age at vaccination

The results showed that dogs vaccinated at four months had a lower response compared to those vaccinated at one to six years (P = 0.025). Dogs over six years are less likely to have a high response than those between one and six years (P = 0.035). Age is therefore a determining factor of the immune response level; dogs aged one to six years are more likely to have a high response to vaccination.

The time interval between the last vaccination and the sample collection for testing.

The rabies antibodies were affected by the intervals between the last rabies shot and the sampling time. The odds ratios of the two types of titration (low response and high response) showed that the longer the interval, the lower the antibody titer (Figure 3). On the other hand, significant differences were observed after 61 days in low responders (P<0.05) and after 91 days in high responders (P<0.1 ) (Table 2).

Type of test

Results showed that for both titer groups (low and high), samples tested by the RFFIT test tend to be higher than those by the FAVN test (P = 0.033 and P = 0.010). The odds ratio for RFFIT was 0.65 for the low-titer versus 1.67 for the high-titer group. These facts suggested that the RFFIT test overestimates the FAVN test (Table 2).

Dogs ‘size

The results showed in Table 2 that the larger the dog (P< 0.001), the less likely it is to reach a high titration level.

Number of vaccinations

Significant differences (P< 0.001) were observed in Table 2 between VO and VT dogs.

Sex

There was no significant difference as revealed in Figure 4 between male and female dogs concerning response to vaccination (P> 0,9 in low responders and P = 0.8 in high responders).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study in Morocco to look at the rabies test results of exported domestic dogs. The results showed that 30.7% of the dogs had a response ≥10 IU/ml, 29.6% had 0.5- 3 IU/ml, and 39.7% had a moderate titer (3-10 IU/ml). This difference in titration level is due to several factors, such as age, size, the number of vaccinations, the type of test, and the time interval between vaccination and collection for titration.

There is usually a relationship between age and antibody levels. In this study, dogs >6 years and those <4 months showed a lower response than those 1- 6 years. According to many studies (Kennedy et al., 2007; Berndtsson et al., 2011), the effects of age on the immune system are manifest at multiple levels, including reduced immune cells production and diminished functions (Montecino-Rodriguez et al., 2013). As a result, elderly individuals do not respond to immune challenges as robustly as the young. Likewise, the low response in dogs <4 months can be explained by their less mature immune system. However, to eradicate rabies in endemic countries, the World Health Organization recommend mass vaccination of dogs regardless of their age (WHO, 2018). Wallace et al. (2017) showed that there is no statistical difference in the failure rate between vaccinated puppies at 12 weeks or earlier (Wallace et al., 2017).

The time interval between the last vaccination and the time of the titration sample is key, as the longer the interval, the lower the titer (Cliquet et al., 2003). According to Yakobson et al. (2017), the risk of obtaining a low titration increases after 60 days from the last vaccination.

Compared to small dogs, large dogs are less likely to have a high titer. Berndtsson et al. (2011) and Kennedy et al. (2007) suggested a vaccine dose effect on the animal response or the fact that larger dogs are more likely to have deeper subcutaneous fat at injection sites that may interfere with the vaccine absorption (Kennedy et al., 2007). The obesity is correlated with poor vaccine-induced immune responses in humans (Painter et al., 2015).

No research has ever been done on titration levels based on the type of test (FAVN or RFFIT) in the context of non-commercial dog movements. The RFFIT test tends to give higher results than the FAVN test as revealed in our results. It can be hard to figure out what the results mean, both when comparing different methods and when making changes to the same method which can lead to wrong conclusions (Moore, 2021).

The current study showed that dogs that received VT responded better than dogs that have VO. This confirms the findings of Zanoni et al. (2010); Tasioudi et al. (2018); Watanabe et al. (2013), where vaccination failures were significantly reduced after a double primary vaccination at an interval of 7 to 10 days. Furthermore, others reported that a single vaccination is not sufficient to maintain protective antibody titers for one year in puppies (Pimburage et al., 2017; Wallace et al., 2017).

No difference in antibody titration was recorded between the females and males. This was reported by Mansfield et al. (2004); Berndtsson et al. (2011) and suggested that sex has no impact on response to rabies vaccination.

CONCLUSION

Many factors, such as age, size, number of boosters, the time between the last vaccination and the titer testing, and the type of test used may affect rabies antibody titers and the response to vaccination in dogs. Dogs that are too old (over six years) or too young (under four months) are less likely to respond to vaccination than those between four months and six years of age. Primary vaccination with two inoculations 2–4 weeks apart, followed by annual boosters, is necessary to maintain protective antibody titers.

The titer was lower when the time between vaccination and testing is longer, and this effect is stronger when the time between tests is more than two months.

Compared to the FAVN test, the RFFIT test overestimates the results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all veterinarians who have facilitated the collection of data within the veterinary services of ONSSA, especially Hicham Mih, Barkouch Abdessadeq, Fatima Kourbi, Chaib Meryem, Ibtihal Rahmouni Alami, Tarik Abdelmoutalib, Seyagh Mohamed Adil, Taha Abdelhamid Sakr, El Hanchi Abedlhamid, El Yagoubi Mohamed, and Motassim El Hanafi.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared that there is no financial or unethical conflict related to this work that can negatively influence its publication.

novelty statement

Morocco is a rabies-endemic country. No study has been carried out in Morocco to evaluate the results of anti-rabies titration in dogs, particularly in the context of international non-commercial movement of pets. This work was carried out to determine the factors influencing this titration, namely age, size, number of boosters, time between last vaccination and titer test, and type of test. Although similar studies exist, the present study added the test type factor.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Saloua Ziani collected the data, designed and conducted the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the article. Khalid Sohaib conducted the statistical analysis and interpreted the results. Ikhlass Elberbri revised and wrote the article. Ouafaa Fassi Fihri and Youssef Lhor contributed to the material and revised and edited the project.

REFERENCES

Berndtsson L. T., Nyman A.-K. J., Rivera E., Klingeborn B. (2011). Factors associated with the success of rabies vaccination of dogs in Sweden. Acta Vet. Scandinav., 53(1): 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-53-22

Cliquet F., Verdier Y., Sagne L., Aubert M., Schereffer J. L., Selve M., Wasniewski M., Servat A. (2003). Neutralising antibody titration in 25,000 sera of dogs and cats vaccinated against rabies in France, in the framework of the new regulations that offer an alternative to quarantine : -EN- -FR- -ES-. Rev. Scient. Tech. de l’OIE, 22(3): 857-866. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.22.3.1437

Day M. J., Horzinek M. C., Schultz R. D., Squires R. A. (2016). WSAVA Guidelines for the vaccination of dogs and cats : WSAVA Vaccination Guidelines. J. Small Anim. Pract., 57(1): E1-E45. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.2_12431

Github (2023). Régression logistique binaire, multinomiale et ordinale. https://larmarange.github.io/analyse-R/regression-logistique.html

Hampson K., Coudeville L., Lembo T., Sambo M., Kieffer A., Attlan M., Barrat J., Blanton J. D., Briggs D. J., Cleaveland S., Costa P., Freuling C. M., Hiby E., Knopf L., Leanes F., Meslin F.-X., Metlin A., Miranda M. E., Müller T., … on behalf of the Global Alliance for Rabies Control Partners for Rabies Prevention. (2015). Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis., 9(4): e0003709. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709

Kennedy L. J., Lunt M., Barnes A., McElhinney L., Fooks A. R., Baxter D. N., Ollier W. E. R. (2007). Factors influencing the antibody response of dogs vaccinated against rabies. Vaccine., 25(51): 8500-8507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.015

Khayli M., Lhor Y., Derkaoui S., Lezaar Y., El Harrak M., Consultant, Former OIE expert, Rabat, Morocco, Sikly L., Department of Waters and Forestry (HCEFLCD), Rabat, Morocco, Bouslikhane, M., & Institute Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II, Rabat, Morocco. (2019). Determinants of Canine Rabies in Morocco : How to Make Pertinent Deductions for Control? Epidemiology – Open J., 4(1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.17140/EPOJ-4-113

Mansfield K. L., Sayers R., Fooks A. R., Burr P. D., Snodgrass D. (2004). Factors affecting the serological response of dogs and cats to rabies vaccination. Vet. Rec., 154(14): 423-426. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.154.14.423

Montecino-Rodriguez E., Berent-Maoz B., Dorshkind K. (2013). Causes, consequences, and reversal of immune system aging. J. Clin. Investigat., 123(3): 958-965. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI64096

Moore S.M. (2021). Challenges of Rabies Serology : Defining Context of Interpretation. Viruses., 13(8): 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13081516

Painter S. D., Ovsyannikova I. G., Poland G. A. (2015). The weight of obesity on the human immune response to vaccination. Vaccine., 33(36): 4422-4429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.101

Pimburage R. M. S., Gunatilake M., Wimalaratne O., Balasuriya A., Perera K. A. D. N. (2017). Sero-prevalence of virus neutralizing antibodies for rabies in different groups of dogs following vaccination. BMC Vet. Res., 13(1): 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1038-z

R. M. Pees, A., Blanton J. B., Moore S. M. (2017). Risk factors for inadequate antibody response to primary rabies vaccination in dogs under one year of age. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis., 11(7): e0005761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005761

Russolillo G. (2018). Modèle Logistique Multinomial et Ordinal. https://maths.cnam.fr/IMG/pdf/mult_ord_log_regr_fr_cle021178.pdf

Tasioudi K. E., Papatheodorou D., Iliadou P., Kostoulas P., Gianniou M., Chondrokouki E., Mangana-Vougiouka O., Mylonakis M. E. (2018). Factors influencing the outcome of primary immunization against rabies in young dogs. Vet. Microbiol., 213: 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.11.006

UCLA. (2023). Multinomial Logistic Regression | R Data Analysis Examples. https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/r/dae/multinomial-logistic-regression/Wallace,

UCLA. (2023). Multinomial Logistic Regression | R Data Analysis Examples.

WOAH (2018). Chapter 3.01.18. Rabies (Infection with rabies virus and other lyssaviruses). In OIE Terrestrial Manual 2018 (p. P 578-614).

Wallace R. M., Pees A., Blanton J. B., Moore S. M. (2017). Risk factors for inadequate antibody response to primary rabies vaccination in dogs under one year of age. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis., 11(7): e0005761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005761

Watanabe I., Yamada K., Aso A., Suda O., Matsumoto, T., Yahiro T., Ahmed K., Nishizono A. (2013). Relationship between Virus-Neutralizing Antibody Levels and the Number of Rabies Vaccinations: A Prospective Study of Dogs in Japan. Japanese J. Infect. Dis., 66(1): 17-21. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.66.17

WHO (2018). WHO expert consultation on rabies : Third report. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272364

Yakobson B., Taylor N., Dveres N., Rotblat S., Spero Ż., Lankau E. W., Maki J. (2017). Impact of Rabies Vaccination History on Attainment of an Adequate Antibody Titre Among Dogs Tested for International Travel Certification, Israel—2010-2014. Zoon. Pub. Health., 64(4): 281-289. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12309

Zanoni G. R., Bugnon Ph., Deranleau E., Nguyen M. V. T., Brügger D. (2010). Walking the dog and moving the cat : Rabies serology in the context of international pet travel schemes. Schweizer Archiv. Für Tierheilkunde, 152(12): 561-568. https://doi.org/10.1024/0036-7281/a000125

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?