Dietary Diversity by Provinces and Administrative Divisions with Rural-Urban Divide in Pakistan

Research Article

Dietary Diversity by Provinces and Administrative Divisions with Rural-Urban Divide in Pakistan

Abid Hussain1*, Bilal Khan Yousafzai1 and Muhammad Ishaq2

1Social Sciences Research Institute, PARC-National Agricultural Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan; 2Social Sciences Division, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Abstract | One of the biggest factors affecting human health and nutrition is diet. The study is based on Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurement Survey (PSLM)/ Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) 2018-19 and PSLM 2013-14 with an objective to determine dietary diversity in Pakistan by provinces and administrative divisions with rural urban divide. The study has been carried out to fill the research gap, as the available literature on food security and dietary diversity in Pakistan primarily focuses on women and children under the age of five. This study is an attempt to cover geographical location wise determination of the dietary diversity in Pakistan. Changes in monthly per capita consumption of high value agricultural commodities from year 2013-14 to 2018-19 has also been determined. The findings of the study are important to suggest recommendations for food dietary improvement in the country. These can be used to develop policies and programs to target administrative divisions with low dietary diversity. It is found that consumption pattern of the people has changed to a substantial extent during the study period. Meat consumption has increased a little in urban areas (1.0%) and decreased to a considerable extent in rural areas (9.3%). Egg consumption has decreased by 30.3% and 24.6 % in urban and rural area, respectively. While, rise in consumption of both fruits and vegetables have occurred over time by more or less half kilogram per capita per month for each. Fruits and vegetable consumption increased by 43.3% and 14.8%, respectively. In the same way, monthly consumption of milk and milk products has increased by 0.55 kg (7.2%) and 0.37 kg (4.5%) per capita in urban and rural areas of the country, respectively. As per PSLM/ HIES 2018-19, people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have the most diversified food pattern followed by Sindh, Punjab and Balochistan. Over time i.e., from 2013-14 to 2018-19, household dietary diversity has improved in all the provinces, except Sindh where a little downfall is occurred in it. Household dietary diversity in Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh provinces improved the most in Quetta, Dera Ismail Khan, Dera Ghazi Khan and Larkana divisions, respectively.

Received | March 19, 2024; Accepted | September 18, 2024; Published | September 30, 2024.

*Correspondence | Abid Hussain, Social Sciences Research Institute, PARC-National Agricultural Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan; Email: abid.parc@gmail.com

Citation | Hussain, A., B.K. Yousafzai and M. Ishaq. 2024. Dietary diversity by provinces and administrative divisions with rural-urban divide in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research, 37(3): 326-337.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjar/2024/37.3.326.337

Keywords | Dietary diversity, Division, Pakistan, Province, Rural, Urban

Copyright: 2024 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Rapid industrialization, urbanization and changing global demography determine modern dietary patterns. The importance of a wide variety of foods containing significant macro and micro-nutrients has long been recognized. Food diversification aims to modify and enhance people dietary behaviours, so that more types of food with better nutritional value are accessible to them (Amanto, 2019). Improved food accessibility for the impoverished, as well as higher nutritional quality and diversity, are necessary for proper human nutrition (Sibhatu et al., 2015). While, the people in Pakistan consume energy dense foods and primarily rely monotonous diets. The burgeoning population, rural to urban migration, poor infrastructure, and high inflation are causing food accessibility issues. Along with this, socioeconomic conditions, lifestyles and dietary habits are changing. Safe food handling and management are lacking to a grave extent. Resultantly, about fifty-percent of the population of the country is deficient in essential nutrients. Moreover, children, women and elderly people are more vulnerable to these deficiencies, and related health risks due to their poor health and nutritional deficiencies. Specifically, women of child bearing age, children below the age of five, and adolescents having higher nutritional requirements are more vulnerable (FAO and GOP, 2019).

Furthermore, sedentary life styles characterized with increasing use of computer gadgets, electronic home appliances and automated machines exacerbate nutrition and health related issues. Unhealthy eating habits and desk-bound way of living lead to increase in prevalence of infectious, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and other chronic diseases (FAO and GOP, 2019). NCDs are the leading reasons of premature deaths, kill 41 million people each year equivalent to 74% of all deaths globally (WHO, 2024). Based on recent literature it is said that unhealthy food and lifestyles are main risk factors for rising number of diseases (GOP, 2012; Jesmin et al., 2011; Jamison et al., 2006; Tharakan and Suchindran, 1999).

Likewise, malnutrition accounts for 50% of deaths in children with 3% loss in GDP per annum in developing world. It also causes loss of one-tenth of the earning potential in effected children (Khan et al., 2007; World Bank, 2006). Similarly, it has been predicted that in United States 0.340 million lives per annuum can be saved from cancer with a nutritious diet, regular physical activity and sustaining a healthy body weight (Lohse et al., 2016). In year 2016, a total of 1.659 million new cancer cases were reported in the United States. Thus, healthy diets and active life style can result in prevention of about one-fifth (20.5%) of the potential cancer cases per year in the country (Rebecca et al., 2016).

The Pakistan dietary guidelines for better nutrition (PDGN) jointly developed by Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Pakistan office and Government of Pakistan (FAO and GOP, 2019) recommend the regular consumption of basic food groups on daily basis viz. meat, pulses, milk, milk products, vegetables and fruits. These guidelines recommend replacement of refined cereals grains and grain products with whole grain cereals. Similarly, it is recommended that consumption of these commodities, eggs and fruits should be augmented in accordance with body needs. It is further advised to reduce the usage of salt, sugar, vegetable ghee, cooking oil, sweets, soft drinks, artificial juices, fruit/flavoured drinks and beverages, refined and processed foods.

Hoddinott and Yohannes (2002) argued that the inability of households to acquire enough food for an active and healthy life is undoubtedly a significant factor in their impoverishment, even though it may not encompass all aspects of poverty. The available literature on food security and dietary diversity in Pakistan and other South Asian nations focuses primarily on women and children under the age of five viz. (Ali et al., 2014; Rafique et al., 2020; Brazier et al., 2020; Baxter et al., 2021) etc. and highlight food insecurity and insufficient dietary diversity in these groups. However, the ethnic and cultural dynamics of the population’s food and dietary practices in Pakistan have not been fully examined. There is a need to investigate more on the basic cultural factors leading to low dietary diversity (Hashmi et al., 2021). The country still is confronting many obstacles, particularly in narrowing the gap between daily intake of people and the least requirement of balanced diet from the food intake. Research on the relationship between diet and ailment in the local context is needed to reduce risk factors for chronic diseases and under and overnutrition. Concrete steps are required to address the nutrition and public health challenges in order to enhance peoples’ health and their quality of life (Eckhardt, 2006).

Keeping all this in view, the study has been carried out to fill the research gap on household level dietary diversity in Pakistan. This study is an attempt to cover geographical location wise determination of the dietary diversity levels in the country. Findings of the study are useful for policy makers, programme managers, nutritionists, medical practitioners, and food and agriculture professionals to develop low-cost policies, plans, and nutrition initiatives that support the production, availability, and consumption of safe, nutrient-dense foods as well as treatments aimed at lowering and controlling the incidence of diet-related illnesses.

Geographical areas in the country having low dietary diversity can be targeted to improve intake of high value agricultural commodities. It is expected that appropriate interventions that could be designed based on the study findings will improve people’s well-being and productive efficiency. Rural-urban divide in the dietary diversity could be minimized to discourage urban migration and achieve successful rural transformation. The findings of study are useful for improving dietary uptake of the people in the country. This study has been conducted with the specific objectives; to review recent literature about factors affecting dietary diversity and human health, to determine changes in per capita consumption of high value agricultural commodities from year 2013-14 to 2018-19 at provincial level with rural urban divide, to determine change in dietary diversity over time at provincial and administrative divisional levels both for rural as well as urban areas ; and to suggest workable recommendations for improvement in it the country.

Materials and Methods

The study is based on both literature review about dietary diversity and human health as well as on secondary data. It is primarily founded on Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM)/Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) 2018-19 and PSLM 2013-14. The data of these surveys is mainly used to assist the government in formulating the poverty reduction strategy as well as development plans. These data sets are representative sample of the population of the country. In PSLM/ HIES 2018-19, 27,062 households and PSLM 2013-14, 19,620 households were covered. Based on these data sets two methodologies viz. Household dietary diversity sores (HDDS) and Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) for the dietary diversity have been used.

HDDS indicates a household’s financial ability to obtain food. FAO (2011) proposed twelve food groups for the HDDS. These food groups are: Cereals, white tubers and roots, vegetables, fruits, meat, eggs, fish and other seafood, legumes, nuts and seeds, milk and milk products, oil and fats, sweets, and spices, condiments and beverages. Through HDDS, dietary diversity scores are computed by adding together number of all of the food types ingested by a household in past one-day recall period. While, in HIES data, quantity of food items consumed over one-month period is captured. Thus, results obtained through this method are also substantiated HHI.

Many researchers have lately employed HHI to quantify dietary diversity viz. (Saydullaeva, 2023; Nandi and Nedumaran, 2022; Akerele et al., 2017). Data for per capita annual consumption of high value agricultural commodities viz. dairy products (milk– fresh and boiled, milk packed, milk dry, milk dry– children, butter, ghee desi, yogurt– loose/packed, mutton, beef, fish, chicken meat, eggs and honey), fruit (banana, citrus fruits–mousami, apple, other fresh fruits, dry fruits etc.) and vegetables (tomato, onion and other vegetables etc.) has been probed over the study period by provinces and administrative divisions to ascertain changes in consumption in rural as well as urban areas of the country. To standardize use of all commodities in kilograms, weight of one egg was considered 49.58 gram and that of one-liter milk was taken 1.03 kilogram (University of Minnesota, 2022; Casey and Holden, 2005).

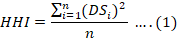

Dietary diversity is considered a good proxy for micronutrient adequacy. However, quantities of food commodities consumed can give a better indication of nutritional status (Ali et al., 2014). Thus, to determine dietary diversity Herfindahl-Hirschman index has been used. The HHI accounts for the number of commodities in the diet, as well as concentration, by incorporating the relative size (that is, diet share) of all commodities in the diet (Rhoades,1993). It is computed by first squaring the shares of each commodity in the diet, and then adding the squares as expressed by Equation 1.

Where DSi represents the share of commodity i and there are n commodities in the diet. HHI gives much heavier weight to commodities with large diet shares than to commodities with small shares as a result of squaring the shares.

Results and Discussion

Factors affecting dietary diversity and human health

A succinct review of literature reveals that household dietary diversity has inverse relationship with severe food insecurity (Hashmi et al., 2021), poverty (Baxter et al., 2021), low-income levels, rapid increase in food intake cost, rural households’ necessity to sell off food items high in energy (honey, chicken, milk, purified butter and eggs) to earn small cash needs, and non-availability of high-quality foods in local markets (Ali et al., 2023; Farooq and Shahid, 2019). While, education level, land holding, age and family size positively effect dietary diversity score in households (Ali et al., 2023). People in far-flung and relatively less developed mountainous regions of the country viz. AJK, GB, northern areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, southern Punjab and south-eastern part of Sindh etc. are more food insecure, have less diversified diets and are vulnerable to economic disasters due to unique topography and limited access to natural resources as indicated by Hussain et al. (2022). In the country, people change their dietary pattern with seasons. In the country, households’ food basket becomes more divers in the winter with 13% increase in dietary diversity (Hussain et al., 2014). It is implicit that poor human health in the country has its roots in poverty, income inequality, nutritional illiteracy and food insecurity. While, poor handling and management of food along with unhygienic preparation foster the menace. People at various stages of life from infancy to elderly age have poor feeding. Likewise, the country is classified as a low-exclusive breastfeeding nation (WHO, 2010, 2023).

The country has high prevalence of stunting in children under five years of age (40%) and wasting (17.7%). Almost one in three children in this age bracket is underweight (28.9%), alongside a high prevalence of overweight (9.5%). Due to poor consumption of milk and milk products and fortified foods, the children are susceptible to deficits in calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D. Children only eat empty, high-energy meals like candy, sweets, soft drinks, tetra pack juices, samosas, crackers, pakoras, rolls, etc. as snacks. These foods don’t satisfy the majority of the body’s needs for macro and micronutrients (GOP, 2019). Similarly, over one-third of teenagers are underweight or stunted, while about 10-30% are overweight or obese. The main cause of this is that a sizable percentage of kids and teenagers don’t routinely eat meat, meat products, fruits, and vegetables, because these are either not readily available to them or because they dislike them personally or don’t know enough about their significance for human health (Safdar et al., 2013; Aziz et al., 2010).

Together with an extremely high frequency of non-communicable diseases, under and overnutrition are major issues facing adults in Pakistan. A quarter or more of individuals suffer from diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular illnesses, cancer, and are deficient in one or more nutrients, such as iron, vitamin A, calcium, vitamin D, zinc, and iodine (GOP, 2012). Globally, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) rank among the main causes of adult disability and premature mortality. Low-income nations are disproportionately affected, as they account for more than 80% of the world’s illness burden and incur enormous yearly health costs equal to billions of dollars (Paracha et al., 2015). According to the National Health Survey (1990–1994), one in three people over 45 years of age have hypertension (GOP, 1995; Jafar et al., 2005); yet, another study reported that 22% of adults had diabetes (Basit et al., 2018). Men were more likely to have diabetes than women were, with a frequency of 23.7% versus 20.6% (Fleming et al., 2004). Data on Pakistan’s demographic, economic, social, nutrition, and health indicators showed that while the nation’s per capita income and household ownership of electric goods, transportation, and communication facilities have improved 37 times, the nation’s nutrition and health indicators have not significantly improved (GOP, 2022).

The elderly require a special diet and medical attention to lower their risk of physical and mental disabilities as well as to control diseases due to their declining health and compromised physiological functions, such as decreased mastication, salivation, gastric secretion, digestive and absorptive capacity combined with decreased physical activity and appetite, loss of lean body mass, and skeletal muscle. According to estimates, more than 72% of Pakistan’s elderly population suffers from five or more health issues, although the country has very few nutrition and health care programs to address these issues (Qidwai, 2009). The prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, cancer, arthritis, and other conditions is rising. This is resulting in higher medical expenses and increased care, which is placing an excessive strain on the health care system and causing billions of rupees in losses as well as an increase in the number of elderly people dying young. The available data on food intake for the elderly population showed that their diet is mostly high in energy density and low in variety, which puts them at risk for nutritional deficiencies, weakened immune systems, and an increased risk of both acute and chronic illness (FAO and GOP, 2019).

Consumption of high value agricultural commodities in Pakistan

Meat consumption in the country as per PSLM/HIES 2018-19 is 0.98 kg and 0.68 kg per capita per month in urban and rural areas of the country, respectively. It has marginally increased in the urban areas (1.0%) and decreased to a considerable extent in rural areas (9.3%) from year 2013-14 to year 2018-19 (Table 1). Over time, consumption of eggs has decreased both in urban as well as rural areas. Eggs consumption in year 2018-19 was 2.78 and 1.78 per capita per month in urban and rural areas, respectively. It has decreased by 1.21 (30.3%) and 0.85 (24.6%) per capita per month in urban and rural area from 2013-14 to 2018-19, respectively. While, during the same time period prices of eggs per dozen increased by just 5.5% i.e., from Rs.97.61 in 2013-14 to Rs.102.93 in nominal term (GOP, 2023). Increase in consumption of both fruits and vegetables have occurred over time by more or less half kilogram per capita per month, each. While, a marginal increase in consumption of tuber and roots has occurred. Monthly consumption of milk and milk products has increased by 0.55 kg (7.2%) and 0.37 kg (4.5%) per capita in urban and rural areas of the country, respectively (Table 1).

Consumption of other commodities

Over five-year span i.e., from 2013-14 to 2018-19 a considerable decrease has occurred in consumption of cereals including wheat and wheat flour i.e., more than five kilograms per capita per month (36.4) decrease in the consumption was recorded both in urban and rural areas (Table 2). The decrease can be attributed mainly to change in consumption pattern i.e., replacement of cereals consumption with other food commodities, as the nominal increase in the support/ procurement prices of wheat during 2013-14 to 2018-19 was just 8.3%. While, mean prices of wheat in the main wholesale markets in the country registered a decrease of 7.9% i.e., decreased from Rs.1437 in 2013-14 to Rs.1324 per 40 kg in 2018-19 (GOP, 2022A). While wheat retail flour prices decreased by 0.68% i.e., from Rs.397.25 in December ,2013 to Rs.394.52 per 10 kg in December, 2018. (GOP, 2018). In spite of a decrease in the consumption, relative share of expenditure on wheat flour and diary items are high in the country (Majeed et al., 2023). However, over time dependence of the people on energy-dense food viz. cereals, fats and sweets has been shifted to a considerable extent to high value agricultural commodities viz. fruits, vegetables, dairy products. Malik et al. (2015) further stressed that prices of wheat should be controlled as an increase in its price may not reduce its consumption due to people’s dietary habits but may result in decline in consumption of other high value foods and decrease in non-food expenditures i.e., education, health and other amenities of life. As per findings of the current study, consumption of legumes, spices and condiments remain almost unchanged over time. On the other hand, consumption of oil and fats increased

Table 1: Monthly per capita consumption of high value agricultural commodities.

|

Commodities |

Units |

2013-14 |

2018-19 |

Change |

||||||

|

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

||

|

Meat1 |

Kg |

0.97± 1.14 |

0.75± 1.31 |

0.83± 1.26 |

0.98± 0.94 |

0.68± 0.71 |

0.79± 0.82 |

0.01(1.0) |

-0.07(-9.3) |

-0.04(-4.8) |

|

Eggs |

No |

3.99± 4.59 |

2.36± 3.28 |

2.92± 3.86 |

2.78± 3.06 |

1.78± 2.40 |

2.14± 2.70 |

-1.21(-30.3) |

-0.58(-24.6) |

-0.78(-26.7) |

|

Fruits2 |

Kg |

1.58± 1.62 |

1.00± 1.09 |

1.20± 1.32 |

2.13± 2.07 |

1.50± 1.66 |

1.72± 1.84 |

0.45(28.5) |

0.57(57.0) |

0.52(43.3) |

|

Vegetables |

Kg |

3.31± 1.74 |

3.31± 3.97 |

3.31± 3.38 |

3.87± 1.77 |

3.76± 1.85 |

3.80± 1.82 |

0.56(16.9) |

0.45(13.6) |

0.49(14.8) |

|

Tubers and roots |

Kg |

1.62± 1.07 |

1.70± 1.35 |

1.68± 1.26 |

1.63± 0.84 |

1.71± 0.91 |

1.68± 0.89 |

0.01(0.6) |

0.01(0.6) |

0.01(0.6) |

|

Milk and milk products3 |

kg |

7.62± 6.39 |

8.29± 11.64 |

8.06± 10.14 |

8.17± 5.89 |

8.66± 6.75 |

8.49± 6.46 |

0.55(7.2) |

0.37(4.5) |

0.43(5.3) |

1: Mutton, Beef, Chicken and Fish; 2: Banana, Citrus Fruits, Apple, Dates, Grapes, Mango, Other and Canned Fruits and Dried Fruits; 3: Milk (Fresh), Milk (Packed), Yougart and Butter; Figures in parenthesis are percentages.

Table 2: Change in per capita monthly consumption of other agricultural commodities in Pakistan.

|

Commodities |

Units |

2013-14 |

2018-19 |

Change |

||||||

|

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

||

|

Cereals1 |

kg |

14.34± 24.41 |

15.13± 30.72 |

14.85± 28.70 |

8.66± 3.05 |

9.87± 3.05 |

9.44± 3.11 |

-5.68 (-39.6) |

-5.26 (-34.8) |

-5.41 (-36.4) |

|

Legumes2 |

Kg |

0.46± 2.04 |

0.39± 1.42 |

0.42± 1.66 |

0.41± 0.27 |

0.40± 1.19 |

0.40± 0.97 |

-0.05 (-10.9) |

0.01 (2.6) |

-0.02 (-4.8) |

|

Oil and fats3 |

kg |

1.15± 0.51 |

1.05± 0.41 |

1.08± 0.45 |

1.22± 0.47 |

1.19± 0.47 |

1.20± 0.47 |

0.07 (6.1) |

0.14 (13.3) |

0.12 (11.1) |

|

Sweets4 |

kg |

1.69± 0.99 |

1.89± 1.15 |

1.82± 1.10 |

1.49± 0.82 |

1.71± 0.91 |

1.63± 0.89 |

-0.2 (-11.8) |

-0.18 (-9.5) |

-0.19 (-10.4) |

|

Spices and condiments5 |

kg |

0.59± 2.74 |

0.54± 0.93 |

0.55± 1.78 |

0.59± 0.27 |

0.54± 0.26 |

0.56± 0.26 |

0.00 (0.0) |

0.00 (0.0) |

0.0 1(1.7) |

1: wheat and wheat flour, and rice and rice flour; 2: Gram whole and split, mash, moong, masoor, other pulses; 3: ghee desi, vegetable ghee and cooking oil; 4: sugar, honey, and gur and shakkar; 5: slat, chilies and other spices. Figures in parenthesis are percentages.

Table 3: HDDS for high value agricultural commodities in provinces.

|

Provinces |

2013-14 |

2018-19 |

Change |

||||||

|

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

|

|

Balochistan |

5.29±1.16 |

5.49±1.19 |

5.33±1.17 |

5.96±0.98 |

6.25±0.86 |

6.05±0.95 |

0.67 |

0.76 |

0.72 |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkwa |

6.12±0.85 |

6.34±0.89 |

6.20±0.88 |

6.34±0.84 |

6.47±0.81 |

6.38±0.84 |

0.22 |

0.13 |

0.18 |

|

Punjab |

5.83±1.16 |

6.18±1.02 |

5.98±1.11 |

6.17±0.91 |

6.38±0.98 |

6.24±0.94 |

0.34 |

0.20 |

0.26 |

|

Sindh |

6.15±0.80 |

6.55±0.94 |

6.27±0.85 |

6.08±0.72 |

6.52±0.72 |

6.25±0.75 |

-0.07 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

by seventy and one-hundred and forty grams per capita per month in both urban and rural areas, respectively. While, that of sweets decreased by 200 and 180 grams per capita per month in urban and rural areas, respectively.

Province and division level dietary diversity

As per PSLM/ HIES 2018-19, people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has the most diversified food pattern followed by in Sindh, Punjab and Balochistan. The results are in line with Majeed et al. (2023), as they reported based on HIES 2018-19 that among the household’s food expenditure pattern dietary diversity exist across the provinces. In the same way, Haider and Zaidi (2017) based on HIES 2013-14 reported that food consumption patterns differ across regions as well as provinces. Through, current study, it is found that over time i.e., 2013-14 to 2018-19, household dietary diversity has improved in all the provinces except Sindh, with a little downfall in it (Table 3). It has improved the most in Balochistan, with 0.72 increase in the household dietary diversity score (HDDS), followed by Punjab (0.26) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (0.18). In the country, people in rural areas have more dietary diversity than urban region in all the provinces. Ullah et al. (2022) reported that there is a significant average difference in the diversity across rural-urban regions. They further described that the difference specifically exists due to households characteristics like household expenditures, household head educational level and age etc. In Balochistan province dietary diversity improved more in rural areas than urban areas. While, the opposite happened in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces. Administrative division wise HDDS results are presented in Table 4. Household dietary diversity in Balochistan province has improved the most in Quetta division with 1.47 gain in the score. In the same way, improvement in other divisions of the province has happened viz. Zhob, Sibbi and Nasirabad. While, a decrease in the dietary diversity occurred in Kalat division, the score dropped down by 0.73. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, as per HDDS scores, diversity in the diet of the people has increased the most in Dera Ismail Khan division, to a great extent in Malakand division and marginally in Hazara division. While, dietary diversity decreased in Bannu and Kohat divisions. In Mardan division dietary pattern of the people remain almost unchanged. In Dera Ghazi Khan division of Punjab province dietary diversity of the people has improved the most, followed by in Sahiwal, Multan, Bahawalpur, Lahore, Sargodha, Gujranwala and Faisalabad divisions. While, over the study period diets of the people remained almost unchanged in Rawalpindi division and Islamabad Capital Territory. Most probably the reason is already better household dietary diversity levels in these areas due to comparatively better access to education, health, income generation opportunities and other amenities of life etc. In Sindh, province, people have diversified

Table 4: HDDS for high value agricultural commodities in Pakistan by administrative divisions.

|

Administrative divisions |

2013-14 |

2018-19 |

Change |

||||||

|

Rural |

Urban |

All |

Rural |

Urban |

All |

Rural |

Urban |

All |

|

|

Balochistan |

|||||||||

|

Quetta |

4.59±1.02 |

5.31±1.13 |

4.82±1.11 |

6.20±0.80 |

6.37±0.78 |

6.29 ±0.80 |

1.61 |

1.06 |

1.47 |

|

Zhob |

5.51±1.09 |

4.93±1.15 |

5.41±1.12 |

6.19±1.00 |

6.19±1.04 |

6.18 ±1.01 |

0.68 |

1.26 |

0.77 |

|

Sibbi |

5.40±1.24 |

5.27 ±1.24 |

5.36 ±1.24 |

6.02 ±0.69 |

5.98 ±0.96 |

6.01 ±0.77 |

0.62 |

0.71 |

0.65 |

|

Nasirabad |

5.66±0.87 |

6.11±0.99 |

5.74±0.91 |

6.00±0.80 |

6.08±0.80 |

6.01±0.76 |

0.34 |

-0.03 |

0.27 |

|

Kalat |

6.49 ±0.73 |

6.71 ±0.45 |

6.54 ±0.68 |

5.66 ±1.17 |

6.31 ±0.81 |

5.81±1.14 |

-0.83 |

-0.4 |

-0.73 |

|

Mekran |

- |

- |

- |

6.20±0.72 |

6.13 ±0.93 |

6.15±0.86 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkwa |

|||||||||

|

5.81 ±0.67 |

5.80±0.53 |

5.97±0.65 |

6.47±0.71 |

6.58±0.61 |

6.49±0.69 |

0.66 |

0.78 |

0.52 |

|

|

Hazara |

6.56±0.63 |

6.72±0.59 |

6.59±0.62 |

6.78±0.51 |

6.58±0.94 |

6.74±0.62 |

0.22 |

-0.14 |

0.15 |

|

Mardan |

6.39±0.92 |

6.47±0.73 |

6.42±0.84 |

6.38±0.83 |

6.47 ±0.85 |

6.41±0.83 |

-0.01 |

0.00 |

-0.01 |

|

Peshawar |

6.30±0.75 |

6.45±0.90 |

6.40±0.86 |

6.26±0.91 |

6.58±0.70 |

6.43±0.82 |

-0.04 |

0.13 |

0.03 |

|

Kohat |

5.99 ±0.92 |

6.35±0.83 |

6.13±0.90 |

6.02±0.88 |

6.28±1.05 |

6.09±0.94 |

0.03 |

-0.07 |

-0.04 |

|

Bannu |

5.73±0.73 |

5.62±1.12 |

5.71±0.83 |

5.55±0.78 |

5.41±0.83 |

5.53±0.79 |

-0.18 |

-0.21 |

-0.18 |

|

Dera Ismail Khan |

5.20±1.11 |

5.60±1.12 |

5.33±1.12 |

5.80±0.94 |

6.20±0.80 |

5.93±0.92 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

|

Punjab |

|||||||||

|

Islamabad |

6.50±1.20 |

6.60±0.62 |

6.58±0.80 |

6.71±0.56 |

6.36±1.32 |

6.55±1.01 |

0.21 |

-0.24 |

-0.03 |

|

Rawalpindi |

6.47±0.86 |

6.57±0.74 |

6.51±0.82 |

6.56±0.69 |

6.59±0.90 |

6.56±0.77 |

0.09 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

|

Sargodha |

5.90±1.01 |

6.00±0.84 |

5.93±0.96 |

6.60±0.88 |

6.31±0.86 |

6.12±0.88 |

0.7 |

0.31 |

0.19 |

|

Faisalabad |

5.99±1.10 |

6.22±1.01 |

6.09±1.07 |

6.12±0.99 |

6.42±0.87 |

6.22±0.97 |

0.13 |

0.2 |

0.13 |

|

Gujranwala |

5.86±1.14 |

6.15±1.09 |

5.98±1.13 |

6.08±0.93 |

6.31±0.83 |

6.15±0.91 |

0.22 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

|

Lahore |

5.78±1.14 |

6.15±1.03 |

6.01±1.09 |

6.10±1.06 |

6.36±1.11 |

6.27±1.10 |

0.32 |

0.21 |

0.26 |

|

Sahiwal |

5.60±1.35 |

6.17±1.00 |

5.75±1.29 |

6.22±0.96 |

6.53±0.74 |

6.28±0.93 |

0.62 |

0.36 |

0.53 |

|

Multan |

5.83±1.09 |

6.06±1.06 |

5.92±1.09 |

6.33±0.74 |

6.45±0.86 |

6.36±0.77 |

0.5 |

0.39 |

0.44 |

|

Dera Ghazi Khan |

5.59±1.22 |

6.20±1.02 |

5.73±1.21 |

6.29±0.79 |

6.42±0.98 |

6.31±0.82 |

0.7 |

0.22 |

0.58 |

|

Bahawalpur |

5.48±1.16 |

5.93±1.21 |

5.63±1.19 |

5.79±0.91 |

6.14±0.95 |

5.87±0.94 |

0.31 |

0.21 |

0.24 |

|

Sindh |

|||||||||

|

Larkana |

5.87±0.89 |

6.33±0.95 |

5.93±0.91 |

6.10±0.61 |

6.42±0.63 |

6.18±0.64 |

0.23 |

0.09 |

0.25 |

|

Sukkur |

6.04±0.83 |

6.37±0.88 |

6.09±0.85 |

6.10±0.72 |

6.38±0.88 |

6.19±0.79 |

0.06 |

0.01 |

0.10 |

|

Hyderabad |

6.28±0.69 |

6.77±0.45 |

6.35±0.69 |

6.12±0.69 |

6.14±0.58 |

6.13±0.65 |

-0.16 |

-0.63 |

-0.22 |

|

Mirpur Khas |

6.14±0.72 |

6.48±0.70 |

6.17±0.72 |

5.61±0.77 |

5.85±0.77 |

5.66±0.78 |

-0.53 |

-0.63 |

-0.51 |

|

Karachi |

6.71±0.60 |

6.56±1.04 |

6.59±0.95 |

6.76±0.60 |

6.75±0.65 |

6.57±0.64 |

0.05 |

0.19 |

-0.02 |

|

Shaheed Benazirabad |

- |

- |

- |

6.03±0.60 |

6.21±0.58 |

6.07±0.80 |

- |

- |

- |

their diet to relatively a considerable extent in Larkana division and to some extent in Sukkur division. While, dietary pattern of the people remained quite unchanged in Karachi division. Though, people in Mirpur Khas reduced dietary diversity.

The results of Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) computed for the dietary diversity are presented in Table 5. The HHI dietary diversity results are in line with the findings of HDDS. In other words, the HHI results reaffirms HDDS findings viz. over time people in Balochistan province has diversified their diets the most, followed by people in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces. While in Sindh province a little decrease in dietary diversity of the people has occurred over time. Herfindahl-Hirschman indexes (HHI) for the dietary diversity by administrative divisions are presented in Table 6. The results are in line with HDDS findings presented in Table 4. Dietary diversity has improved the most in Quetta division of Balochsitan, followed by in Zhob, Sibbi and Nasirabad divisions. However, it has decreased in

Table 5: HHI for high value agricultural commodities in provinces.

|

Provinces |

2013-14 |

2018-19 |

Change |

||||||

|

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

Urban |

Rural |

All |

|

|

Balochistan |

29.32± 12.06 |

31.58± 12.57 |

29.8812.25 |

36.53(10.92) |

39.77± 9.86 |

37.58± 10.69 |

7.21 |

8.19 |

7.7 |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkwa |

38.19± 9.86 |

40.99± 9.78 |

39.22(9.92) |

40.90(9.87) |

42.64± 9.15 |

41.46± 9.68 |

2.71 |

1.65 |

2.24 |

|

Punjab |

35.39± 12.38 |

39.25± 11.10 |

36.98(12.02) |

38.91(10.18) |

41.72± 10.16 |

39.85± 10.26 |

3.52 |

2.47 |

2.87 |

|

Sindh |

38.49± 9.26 |

43.78± 9.16 |

39.89(9.52) |

37.46(8.43) |

42.99± 8.21 |

39.87± 8.77 |

-1.03 |

-0.79 |

-0.02 |

Table 6: HHI for high value agricultural commodities in Pakistan by administrative divisions.

|

Adminis-trative divisions |

2013-14 |

2018-19 |

Change |

||||||

|

Rural |

Urban |

Rural |

Rural |

Rural |

All |

Rural |

Urban |

All |

|

|

Balochistan |

|||||||||

|

Quetta |

22.12± 9.87 |

29.52± 11.81 |

24.52± 11.09 |

39.15±9.44 |

41.19±9.16 |

40.16±09.35 |

17.03 |

11.67 |

15.64 |

|

Zhob |

31.52± 11.72 |

25.63± 11.26 |

30.59± 11.83 |

39.29±10.89 |

39.46±10.16 |

39.32±10.76 |

7.77 |

13.83 |

8.73 |

|

Sibbi |

30.70± 12.61 |

29.32± 12.86 |

30.31± 12.65 |

36.78±8.20 |

36.72±10.57 |

36.76±08.88 |

6.08 |

7.40 |

6.45 |

|

Nasirabad |

32.84± 9.63 |

38.38± 10.83 |

33.80± 10.05 |

36.56±8.38 |

37.64±9.46 |

36.79±08.63 |

3.72 |

-0.74 |

2.99 |

|

Kalat |

42.65± 8.30 |

45.28± 5.96 |

43.35± 7.81 |

33.45±12.79 |

40.45±9.61 |

35.06±12.48 |

-9.2 |

-4.83 |

-8.29 |

|

Mekran |

- |

- |

- |

38.99±8.81 |

38.45±10.87 |

38.65±10.12 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkwa |

|||||||||

|

Malakand |

34.24± 7.59 |

33.97± 5.94 |

34.19± 7.32 |

42.43±8.49 |

43.64±7.57 |

42.67±8.32 |

8.19 |

9.67 |

8.48 |

|

Hazara |

43.45± 7.70 |

45.52± 6.73 |

43.87± 7.56 |

46.26±6.21 |

44.24±9.09 |

45.87±6.90 |

2.81 |

-1.28 |

2.00 |

|

Mardan |

41.73± 9.70 |

42.40± 8.74 |

42.02± 9.29 |

41.45±9.52 |

42.60±9.35 |

41.87±9.46 |

-0.28 |

0.20 |

-0.15 |

|

Peshawar |

40.24± 9.06 |

42.49± 9.42 |

41.76± 9.36 |

40.05±10.47 |

43.75±8.21 |

42.02±9.51 |

-0.19 |

1.26 |

0.26 |

|

Kohat |

36.75± 10.47 |

41.03± 9.67 |

38.45± 10.35 |

37.04±10.22 |

40.58±11.35 |

38.5±10.65 |

0.29 |

-0.45 |

0.05 |

|

Bannu |

33.42± 8.32 |

32.87± 10.97 |

33.29± 8.97 |

31.45±8.37 |

29.98±9.10 |

31.20±8.50 |

-1.97 |

-2.89 |

-2.09 |

|

Dera Ismail Khan |

28.34± 11.86 |

32.60± 12.63 |

29.66± 12.24 |

34.50±10.89 |

39.12±9.51 |

36.01±10.67 |

6.16 |

6.52 |

6.35 |

|

Punjab |

|||||||||

|

Islamabad |

43.65± 10.47 |

43.97± 7.63 |

43.89± 8.34 |

45.41±6.94 |

42.22±11.26 |

43.88±9.38 |

1.76 |

-1.75 |

-0.01 |

|

Rawalpindi |

42.65± 9.30 |

43.79± 8.08 |

43.12± 8.82 |

43.50±8.20 |

44.21±8.78 |

43.74±8.40 |

0.85 |

0.42 |

0.62 |

|

Sargodha |

35.81± 10.96 |

36.77± 9.73 |

36.15± 10.54 |

37.56±10.16 |

40.59±9.96 |

38.25±10.18 |

1.75 |

3.82 |

2.10 |

|

Faisalabad |

37.15± 11.53 |

39.69± 10.86 |

38.32± 11.29 |

38.47±10.47 |

42.01±9.48 |

39.67±10.28 |

1.32 |

2.32 |

1.35 |

|

Gujranwala |

35.65± 12.56 |

39.02± 11.83 |

37.01± 12.37 |

37.85±10.46 |

40.61±9.45 |

38.71±10.23 |

2.20 |

1.59 |

1.70 |

|

Lahore |

34.71± 12.35 |

38.89± 11.20 |

37.34± 11.81 |

38.41±11.03 |

41.76±10.96 |

40.61 ±11.10 |

3.70 |

2.87 |

3.27 |

|

Sahiwal |

33.14± 13.62 |

39.04± 11.36 |

34.75± 13.29 |

39.67±10.32 |

43.29 ±8.70 |

40.38 ±10.12 |

6.53 |

4.25 |

5.63 |

|

Multan |

35.18± 11.94 |

37.87± 11.33 |

36.23± 11.77 |

40.65 ±8.92 |

42.33 ±9.43 |

41.10 ±09.09 |

5.47 |

4.46 |

4.87 |

|

Dera Ghazi Khan |

32.79± 12.67 |

39.48± 11.26 |

34.31± 12.67 |

40.26±9.36 |

42.18±10.24 |

40.57 ±09.52 |

7.47 |

2.70 |

6.26 |

|

Bahawalpur |

31.48± 12.51 |

36.68± 12.44 |

33.11± 12.71 |

34.38±10.00 |

38.69±10.75 |

35.36 ±10.33 |

2.90 |

2.01 |

2.25 |

|

Sindh |

|||||||||

|

Larkana |

35.29± 9.75 |

41.01± 10.22 |

36.05± 10.00 |

37.58±7.47 |

41.69±7.84 |

38.64±7.78 |

2.29 |

0.68 |

2.59 |

|

Sukkur |

37.21± 9.61 |

41.38± 9.61 |

37.77± 9.71 |

37.82±8.58 |

41.52±9.75 |

38.91±9.09 |

0.61 |

0.14 |

1.14 |

|

Hyderabad |

39.99± 8.36 |

46.01± 5.80 |

40.91± 8.30 |

37.96±8.17 |

38.13±6.95 |

38.01±7.81 |

-2.03 |

-7.88 |

-2.90 |

|

Mirpur Khas |

38.24± 8.61 |

42.52± 8.55 |

38.58± 8.68 |

32.13±8.39 |

34.87±8.58 |

32.64±8.49 |

-6.11 |

-7.65 |

-5.94 |

|

Karachi |

45.41± 7.01 |

44.09± 9.52 |

44.41± 8.99 |

46.12±6.76 |

45.99±6.94 |

46.01±6.92 |

0.71 |

1.90 |

1.60 |

|

Shaheed Benazirabad |

- |

- |

- |

36.81±7.17 |

38.92±7.20 |

37.30±7.23 |

- |

- |

- |

Kalat division of the province over the study period. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, dietary diversity of people has improved the most in Malakand, Dera Ismail Khan and Hazara divisions. While, dietary diversity decreased in Bannu division. It remained almost unchanged in Peshawar and Kohat divisions. HHI findings are nearly in line with that of HDDS for Punjab province. Dietary diversity has improved the most in Dera Ghazi Khan division, followed by in Sahiwal, Multan, Bahawalpur, Lahore, Sargodha, Gujranwala and Faisalabad divisions. While, diets of the people remained almost unchanged in Rawalpindi division and Islamabad Capital Territory. Similarly, results obtained through HHI for Sindh Province reaffirm that the findings computed through HDDS. People in the province have diversified their diet the most in Larkana division, followed by in Karachi and Sukkur divisions. While, over the time period of the study, dietary pattern of the people got less diversified in Mirpur Khas and Hyderabad divisions.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Findings of the study revealed that overtime with rise in per capita income and health awareness people in the country have diversified their dietary intake. Consumption of high value commodities has increased and that of cereals, sweets and legumes decreased. Results based on the most recent data set showed that people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has the most diversified diets, followed by in Punjab and Sindh. These provinces are almost at par in the dietary diversity. While dietary diversity is quite low in Balochistan province. Over time, household dietary diversity has improved in all the provinces, except in Sindh province as a little decrease has occurred in it. In the country, people in rural areas have more diversified diets than in urban regions. In all the provincial capital divisions except Quetta, in the Islamabad Capital Territory and in the Rawalpindi, division diets of the people remained almost unchanged over the study period. It is suggested that administrative divisions/ areas with low dietary diversity should be targeted through effective policy formulation and program designing to improve peoples diets and nutrition in these areas. Access to nutritious food and income opportunities should be increased. Dietary diversity and nutrition should be compulsory part of educational curricula at school level. Women, Youth and elderly people should have awareness about dietary guidelines for better nutrition. This can be done through mass campaigns as well as social media forums. Regular health screening and special care for vulnerable people should be done. Small farmers should be supported to diversify crops and produce high-nutrient foods. Market access for diversified high-quality foods should be improved through better infrastructure development and market access. The areas that are not covered in PSLM/HIES e.g., Gilgit-Baltistan, AJK and newly merged tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa should also be targeted for dietary diversity determination. It would be better to separately carry out dietary diversity survey in all part of the country by applying 24-hours recall period.

The authors are indebted to the management of ANU/ACIAR MOU (No. ADP/2017/024) project ‘Understanding the drivers of successful and inclusive rural regional transformation: Sharing experiences and policy advice in Bangladesh, China, Indonesia and Pakistan’ for technical input in designing the study. In this reference, Dr. Chunlai Chen, Professor, ANU, Canberra, Australia; Dr. Dong Wong, Post-Doctoral Fellow, ANU, Canberra, Australia and Dr. Abaidullah, Associate Professor, PIDE, Islamabad/ Project Team Leader, Pakistan Component are acknowledged for their guidance in undertaking the research.

Novelty Statement

The study has been carried out to fill the research gap on household level dietary diversity in Pakistan. This study is an attempt to cover geographical location wise determination of the dietary diversity levels in the country. Recent literature about factors affecting dietary diversity and human health has been reviewed. Findings of study are useful for improving dietary uptake of the people in the country. These are useful for policy makers, programme managers, nutritionists, medical practitioners, and food & agriculture professionals to develop low-cost policies, plans, and nutrition initiatives that support the production, availability, and consumption of safe, nutrient-dense foods as well as treatments aimed at lowering and controlling the incidence of diet-related illnesses.

Author’s Contribution

Abid Hussain: Designed the study, guided in data analysis, formulated tables, reviewed relevant literature, prepared the draft article, incorporated comments of the anonymous reviewers to finalize it.

Bilal Khan Yousafzai: Accessed and anlyzed data, furnished results as per table formulation suggested by the first author.

Muhammad Ishaq: Guided at each and every step of the research process.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Akerele, D., R.A. Sanusi, O.A. Fadare and O.F. Ashaolu. 2017. Factors influencing nutritional adequacy among rural households in Nigeria: How does dietary diversity stand among influencers? Ecol. Food Nutr., 56(2): 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2017.1281127

Ali, F., I. Thaver and S.A. Khan. 2014. Assessment of dietary diversity and nutritional status of pregnant women in Islamabad, Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad, 26(4): 506-509.

Ali, H., H. Shafiq, M.M. Ali, N. Iftikar and S. Naseer. 2023. Exploring the factors that affect household higher food intake cost and economic instability in Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Entrep., 3(1): 546-565. https://doi.org/10.58661/ijsse.v3i1.125

Amanto, B.S., M.C.B. Umanailo, R.S. Wulandari, T. Taufik and S. Susiati. 2019. Local consumption diversification. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res., 8(8): 1865-1869.

Aziz, S., Umme-e-Rubab, W. Noorulain, R. Majid, K. Hosain, I.A. Siddiqui and S. Manzoor. 2010. Dietary patterns, height, weight centile and BMI of affluent school children and adolescents from three major cities of Pakistan. J. Coll. Phys. Surg. Pak., 20: 10-16.

Basit, A., A. Fawwad, H. Qureshi and A.S. Shera. 2018. Prevalence of diabetes, pre-diabetes and associated risk factors: second National Diabetes Survey of Pakistan (NDSP), 2016–2017. Br. Med. J. Open, 8(8): e020961. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020961

Baxter, J.A.B., Y. Wasan, M. Islam, S. Cousens, S.B. Soofi, I. Ahmed, D.W. Sellen and Z.A. Bhutta. 2022. Dietary diversity and social determinants of nutrition among late adolescent girls in rural Pakistan. Maternal Child Nutr., 18(1): e13265. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13265

Brazier, A.K.N., N.M. Lowe, M. Zaman, B. Shahzad, H. Ohly, H.J. McArdle, U. Ullah, M.R. Broadley, E.H. Baily, S.D. Young, S. Tishkovskaya and M.J. Khan. 2020. Micronutrient status and dietary diversity of women of reproductive age in rural Pakistan. Nutrients, 12(11): 3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113407

Casey, J.W. and N.M. Holden. 2005. The relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and the intensity of milk production in Ireland. J. Environ. Qual., 34(2): 429-436. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2005.0429

Eckhardt, C.L., 2006. Micronutrient malnutrition, obesity, and chronic disease in countries undergoing the nutrition transition: Potential links and program/policy implications. Discussion Paper No. 213. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division. International Food Policy Research Institute. Washington, D.C., United States of America.

FAO and GOP. 2019. Pakistan dietary guidelines for better nutrition. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy and Ministry of Planning Development and Reform, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

FAO, 2011. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy.

Farooq, A. and M. Shahid. 2019. Understanding food insecurity experiences, dietary perceptions and practices in the households facing hunger and malnutrition in Rajanpur district, Punjab Pakistan. Pak. Perspect., 24(2): 115-123.

Fleming, D.M., F.G. Schellevis and V.V. Casteren. 2004. The prevalence of known diabetes in eight European countries. Eur. J. Publ. Health, 14(1): 10-14. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/14.1.10

GOP, 1995. National Health Survey (1990-94). Pakistan Medical Research Council, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

GOP, 2012. National Nutrition Survey 2011. Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform/Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan.

GOP, 2018. Average Monthly prices of essential items. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Ministry of Planning, Development and Special Initiatives. Government of Pakistan. Islamabad.

GOP, 2019. National Nutrition Survey 2018. Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform/Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan

GOP, 2022. Agricultural Statistics of Pakistan 2021-22. Economic Wing. Ministry of National Food Security and Research. Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

GOP, 2022. Social Indictors of Pakistan 2021. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Ministry of Planning, Development and Special Initiatives. Government of Pakistan. Islamabad.

GOP, 2023. Pakistan Economic Survey 2022-23. Economic Adviser’s Wing. Finance Division. Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

Haider, A. and M. Zaidi. 2017. Food consumption patterns and nutrition disparity in Pakistan. MPRA Paper No. 83522

Hashmi, S., N.F. Safdar, S. Zaheer and K. Shafique. 2021. Association between dietary diversity and food insecurity in urban households: A cross-sectional survey of various ethnic populations of Karachi, Pakistan. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 14: 3025-3035. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S284513

Hoddinott, J. and Y. Yohannes. 2002. Dietary diversity as a food security indicator. Discussion Paper No. 136. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division. International Food Policy Research Institute. Washington, D. C., United States of America.

Hussain, A., F. Zulfiqar and A. Saboor. 2014. Changing food patterns across the seasons in rural Pakistan: Analysis of food variety, dietary diversity and calorie intake. Ecol. Food Nutr., 53: 119-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2013.792076

Hussain, A., S. Khan, S. Liaqat and Shafiullah. 2022. Developing evidence-based policy and programmes in mountainous specific agriculture in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral regions of Pakistan. Pak. J. Agric. Res., 35(1): 181-196. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjar/2022/35.1.181.196

Jafar, T.H., F.H. Jafary, S. Jessani and N. Chatury. 2005. Heart disease epidemic in Pakistan: Women and men at equal risk. Am. Heart J., 150: 221-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.025

Jamison, D.T., R.G. Feachem, M.W. Makgoba, E.R. Bos, F.K. Baingana, K.J. Hofman, and K.O. Rogo. 2006. Disease and mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank, Washington, D.C., United States of America.

Jesmin, A., S.S. Yamamoto, A.A. Malik and A. Haque. 2011. Prevalence and determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children: A cross sectional study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr., 29: 494-499. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v29i5.8903

Khan, AA., N. Bano and A. Salma. 2007. Child Malnutrition in South Asia: A comparative perspective. South Asian Survey. 4: 129-145. https://doi.org/10.1177/097152310701400110

Lohse, T., D. Faeh, M. Bopp and S. Rohrmann. 2016. Adherence to the cancer prevention recommendations of the world cancer research fund/ American institute for cancer research and mortality: A census-linked cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 104(3): 678-685. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.135020

Majeed, R., W. Qureshi, M.I. Khan and M. Fazal. 2023. Examining dietary diversity across provinces in Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Arch., 6(2): 01-12.

Malik, S.J., H. Nazli and E. Whitney. 2015. Food consumption patterns and implications for poverty reduction in Pakistan. Pak. Dev. Rev., pp. 651-669.

Nandi, R. and S. Nedumaran. 2022. Rural market food diversity and farm production diversity: Do they complement or substitute each other in contributing to a farm household’s dietary diversity? Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 6: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.843697

Paracha, PI., H. Waheed, S.I. Paracha, Shahidullah and S.S. Bano. 2015. Cardiovascular diseases in relation to anthropometric, biochemical and dietary intake in women: A case control study. Obes. Res. Open. J., 2: 32-38. https://doi.org/10.17140/OROJ-2-106

Qidwai, W. 2009. Ageing population: status, challenges and opportunities for health care providers in Pakistan. J.Coll. Phys. Surg. Pak., 19 (7): 399-400.

Rafique, I., A.N.S. Muhammad, N. Murad, M.K. Munir, A. Khan, R. Irshad, T. Rahit and S. Naz. 2020. Adherence to Pakistan dietary guidelines–Findings from major cities of Pakistan. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.06.20147017

Rebecca, L. S., M.P.H. Siegel, D. Kimberly, M.P.H. Miller and A. Jemal. 2016. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin., 66: 7-30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21332

Rhoades, S.A. 1993. The herfindahl-hirschman index. Board’s Division of Research and Statistics, Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., United States of America.

Safdar, N.F., E. Bertone-Johnson, L. Cordeiro, T.H. Jafar and N.L. Cohen. 2013. Dietary patterns of Pakistani adults and their association with sociodemographic, anthropometric and lifestyle factors. J. Nutr. Sci., 2: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2013.37

Saydullaeva, F., 2023. Innovative solutions to increase dietary diversity of rural households. Am. J. Agric. Sci., Eng. Tech., 7(2): 16-20. https://doi.org/10.54536/ajaset.v7i2.1552

Sibhatu, K.T., V.V. Krishna and M. Qaim. 2015. Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 112(34): 10657-10662. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510982112

Tharakan, C.T. and C.M. Suchindran, CM. 1999. Determinants of child malnutrition-An intervention model for Botswana. Nutr. Res., 19: 843-860. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0271-5317(99)00045-7

Ullah, I., A. Shah and A. Rahman. 2022. Exploration of dietary diversity heterogeneity across rural-urban areas in Pakistan: Based on HIES 2018-19. J. Dev. Soc. Sci., 3(3): 126-138. https://doi.org/10.47205/jdss.2022(3-III)14

University of Minnesota, 2022. Safety tips for handling farm fresh eggs. Available at: https://extension.umn.edu/preserving-and-preparing/safety-tips-handling-farm-fresh-eggs. Last accessed on 1st June, 2024.

WHO, 2010. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Part III country profile. World Health Organization, Geneva.

WHO, 2023. Infant and young child feeding. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/ [Accessed 2 June, 2024].

WHO, 2024. Noncommunicable diseases: Key facts. Available at : https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases [Accessed 1 June, 2024].

World Bank. 2006. Repositioning nutrition as central to development: A strategy for large scale action: World Bank, Washington D.C., United States of America.

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?