Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences

Research Article

Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in Buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Marshes of South of Iraq

Ibrahim A. Mohammed, Jenan M. Khalaf, Abdulkarim J. Karim*

Department of Internal and Preventive Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq.

Abstract | This study was conducted to investigate the incidence of pasteurellosis in buffaloes in marshes of south of Iraq. Out of 5000 buffaloes, 293 (253 from marshes area, 40 from slaughter house) of different ages and sexes, in a period extended from 25/5/2017 to 24/12/2017, were clinically examined. Nasal swabs and blood samples were taken from alive and slaughtered animals, and tracheal swabs from the later. The clinical signs of pasteurellosis characterized by fever, anorexia, respiratory distress, profuse salivation and throat edema. Selective media and Gram stain were used for diagnosis of Pasteurella spp and confirmed by API 20E which correctly identified positive isolates. All positive PCR confirmed cases as P.multocida resulted a 460 bp species-specific using the KMT1T7 and KMT1SP6 primers. The distribution of clinical Pasteurella multocida infection (28%) was significantly higher (P≤0.05) than non-diseased (14%). At high significant differences (P≤0.05), Pasteurella multocida were isolated from nasal swabs (20.9% and 10%), blood samples (2.8% and 0%) from buffaloes at marshes and slaughter house, respectively. Pasteurella multocida was recorded at 5%fromtracheal swabs in slaughter house. Prevalence of pasteurellosis was significantly higher in May (33%) than in October (9%), ages under 1 year (27.1%)showed higher infection rate than the elderly (16.1%), while male buffaloes showed non-significant higher morbidity than female. It is concluded that buffaloes under 1 year old are more prone to hemorrhagic septicemia caused by Pasteurella multocida. These cases may evolve into outbreaks similar to that occurred in marshes of south of Iraq between 2008 and 2012.

Keywords | Pasteurella multocida, Buffaloes, Marshes, Iraq.

Editor | Kuldeep Dhama, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Received | August 12, 2018; Accepted | October 04, 2018; Published | November 02, 2018

*Correspondence | Abdulkarim J Karim, Department of Internal and Preventive Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq; Email: karimjafar59@yahoo.com

Citation | Mohammed IA, Khalaf JM, Karim AJ (2019). Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in marshes of south of iraq. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 7(1): 12-16.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.aavs/2019/7.1.12.16

ISSN (Online) | 2307-8316; ISSN (Print) | 2309-3331

Copyright © 2019 Mohammed et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

INTRODUCTION

Pasteurella, a Gram-negative coccobacillus, causes many diseases in humans and a wide range of animal species, including poultry, ruminant, cats, pigs and dogs (Al-Ani et al., 1997; Sarangi et al., 2014; Narsana and Farhat, 2015; Shirzad-Aski and Tabatabaei, 2016). Pasteurella multocida infects the lungs, nasopharynx and tonsils and may be disseminated to other organs (Al-Haddawi et al., 2000; Lainson et al., 2002; Davies et al., 2003). According to its capsular antigen, it is classified into A, B, D or E serogroups. Serotype D causes atrophic rhinitis and snuffles in pig and rabbits, respectively (Merza, 2008; Constable et al., 2017), while the rest are incriminated in economically important diseases, including respiratory disease and hemorrhagic septicemia in ruminants and fowl cholera in chicken. It is a part of natural flora of the buccal-pharyngeal region and the animals under stress, e.g. transportation, overcrowding, bad nutrition and ventilation, can easily expose to infection. Bacteria grow and proliferate in this region and later extend to the lower respiratory tract and cause hemorrhagic septicemia or pneumonic pasteurellosis (Abusalab et al., 2003; Soure, 2007; Shivachandra et al., 2011).

Typical clinical manifestations of hemorrhagic septicemia caused by B:2 (in Asia) or E:2 (in Africa) strains of Pasteurella multocida include fever, respiratory distress with nasal discharge, frothy saliva, ended by recumbency and death (Shah and Graaf, 1997; Abusalab et al., 2003). On the other hand, mortalities due to infection with serotypes A are mainly attributed to pneumonia. Septicemia is a prominant characteristic feature in all pasteurellosis forms. The incubation period lasts from 3 to 5 days. In peracute cases, sudden death occurs without any clinical signs (Abusalab et al., 2003; Radostits et al., 2007).

Moreover, pasteurellosis has been recorded in wild mammals, globally. In many Asian countries, outbreaks mostly occur during seasons of high humidity and high temperatures (Kumar et al., 1996; Gadi et al., 2010). In southern Iraq, many outbreaks flared up in in marshes affecting cattle and buffaloes (Al-Hamed, 2010; Salah, 2012; Al-Shemmari, 2013; Waffa et al., 2014). The aim of this study was to study the prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes in marshes of south of Iraq.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals of Study

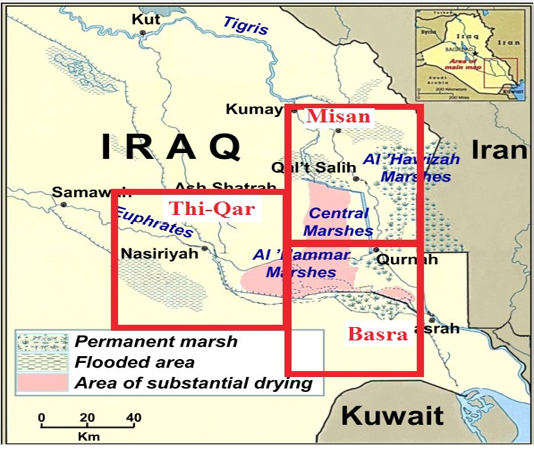

The survey study was conducted on buffaloes in Marshes of south of Iraq in Thi-Qar, Basra and Misan provinces (Figure 1). Out of 5000 buffaloes, 293 animals (253 from marshes area and 40 from slaughter house) with different age and sex were examined clinically during the period extended from 25/5/2017 to 24/12/2017. All tests were carried out in the Lab of Dept of Internal and Preventive Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine-University of Baghdad, and the experiment was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no. 1751/28 April 2017).

Samples Collection

Nasal swabs and blood samples were taken from each examined animal in the marshes area and slaughterhouse and tracheal swabs were taken after slaughtering.

Culture and Staining

Identification of P. multocida was cultured on selective media (MacConkey Agar, Brain heart infusion broth (BHI) and Blood Agar). Gram’s stain and biochemical tests were conducted using commercial API 20E® from Biomerieux company (Quinn et al., 2004).

Conventional PCR Study

Conventional PCR assay was used for detection of Pasteurella multocida by amplification of universal primers of conserved region in (KMT-1) gene in Pasteurella multocida bacterium. The PCR was carried out after DNA extraction according to Townsend et al. (1998) following the instruction of Bioneer company (Korea). A pair of P. multocida specific primer was used

KMT1SP6 5’- GCT GTA AAC GAA CTC GCC AC-3’

KMT1T7 5’- ATC CGC TAT TTA CCC AGT GG –3’

Statistical Analysis

One-way Analysis of Variance was performed to compare the mean±SE at the 0.05 level with statistical package for social sciences (Snedecor and Cochran, 1994).

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Survey Study

Clinically, some buffaloes (125 heads) revealed respiratory infection manifested by anorexia, elevated body temperature, depression and restlessness. Respiratory sounds were present in most cases, profuse salivation, dyspnea and mucoid nasal discharge and throat edema (Figure 2). The rest of buffaloes (128 heads) were clinically healthy. Throat edema and other extended edema were produced following increase capillary permeability due to endotoxemia following infection (Radostits et al., 2007; Constable et al., 2017). Acute inflammatory reaction occurs in response to the release of inflammatory substances, which in return, submandibular edema is developed (Shafarin et al., 2009). Such clinical findings were recorded due to hemorrhagic septicemia (Al-Hamed, 2010; Salah, 2012; Waffa et al., 2014). Whereas Alfaris et al.(2010) reported that domestic cow and buffaloes had fever (40.5-42.2oC), anorexia salivation, edema of neck in varying degrees in the submandibular region, and open mouth breathing, those signs were related to acute severe illness.

Culture, Staining and Biochemical Results

The colony of Pasteurella multocida on blood agar appeared as rough and small discrete tear shaped colonies. Other colonies were mucoid and large. Blood agar showed no haemolysis and no growth appeared on MacConkey agar. Gram staining of the colonies appeared as Gram negative, single or paired coccobacilli or short-rod (Figure 3). The API 20E showed that all biochemical tests were negative except indole and oxidase and the percentage of diagnosis was 92%. Our findings were coincided by the reports of Boot et al. (2004), Lizarazo et al. (2006), Al-Shemmari (2013) and Waffa et al. (2014).

Figure 2: Showed buffalo with edema in throat

Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay

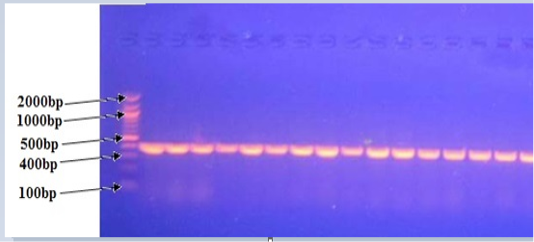

All positive PCR confirmed P.multocida isolates yielded the 460 bp species-specific in agarose gel electrophoresis using KMT1T7 and KMT1SP6 primers (Figure 4). These findings were coincided with results obtained by Townsendet al. (1998), Arumugam et al. (2011) and Salah (2012) who reported a 460 bp from all P. multocida isolates.

The Prevalence Infarm and Slaughter House

Pasteurella multocida is a part of natural flora of the buccal-pharyngeal region. Animals under stress are highly prone to respiratory tract infections. Bacterial isolation from blood is achieved only in the septicemic phase. The prevalence of Pasteurella multocida was isolated significantly higher (P≤0.05) from diseased buffaloes (28%) with clinical symptoms than non-diseased (14%) (Table 1), in concomitant with significantly higher isolation from nasal swabs (21%) than blood samples (3%) (Table 2) and similar findings were reported in slaughter house (Table 3). Our findings agreed with Gadi (2010) and Al-Hamed (2010) but they were lower than the records of Al-Shemmari (2013). Important predisposing stress conditions include poor sanitation, poor ventilation, overcrowding, exposure to cold, wet weather, transportation for long distance, exhaustion and mixed infection with parainfluenza-3 viruses (Gillespie and Timoney, 1981; Radostits et al., 2007).

Table 1: Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes according to clinical signs

| Mean ±SE | Prevalence | +ve | Samples | Clinically |

| 0.28±0.064 * | 28 | 35 | 125 | Diseased |

| 0.14±0.049 * | 14 | 18 | 128 | Non Diseased |

| 21 | 53 | 253 | Total |

* significant variation at (P≤0.05)

Table 2: Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes according to samples examined

| Mean ±SE | % | +ve | Total | Samples |

|

0.21±0.06 * |

21 | 53 | 253 | Nasal |

|

0.03±0.03 * |

3 | 1 | 35 | Blood |

* significant variation at (P≤0.05)

Table 3: Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes according to samples taken at slaughter house

| Mean ±SE | % | +ve | No. | Sample |

|

0.0±0.0 |

0 | 0 |

40 |

Blood |

|

0.10±0.023 * |

10 | 4 | 40 | Nasal |

|

0.05±0.026 * |

5 | 2 | 40 | Tracheal |

* significant variation at (P≤0.05)

The Prevalence According to Time, Sex and Age

The occurrence of Pasteurella moltucida infection, in clinical cases, was reported the highest during May (33%), and decline in October (9%). As well as, the infection records in male were non-significant higher than that in female. Unlike, Hajikolaei et al. (2008) didn’t find any difference between male and female. Allages are susceptible, but age group between 6 months to 2 years are more prone to infection as it recorded (27.1%) in ages under one year, a significantly higher than elderly (Table 4). This may be attributed to the development of immunity. Septicemic pasteurellosis occurs in outbreak during environmental stress (Radostits et al., 2007). Our finding is coincided with Al-Shemmari (2013), DelAwis and Vipulasiri (1981), and Khan et al. (2011) as they found that young animals were more susceptible to pasteurellosis than adult in endemic area. The Pasteurella multocida was isolated from Dhi-Qar then Basra and to a lower extent from Misan with no significance (P≤0.05)and this variation may depend on time of taking samples and the same environment of these governorates (Table 5).

Table 4: Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes according to month

| +ve | Samples | ||

| 7(35%)* | 20 | May |

Month (2017) |

| 7(29%) | 24 | June | |

| 8(24%) | 34 | July | |

| 9(24%) | 38 | August | |

| 7(22%) | 32 |

September |

|

| 3(9%)* | 34 | October | |

| 5(14%) | 36 | November | |

| 7(20%) | 35 | December | |

| 53 | 253 | Total | |

| 24(18%) | 133 | Female |

Sex |

| 29(24%) | 120 | Male | |

| 53 | 253 | Total | |

| 29(27.1) | 107 | < 1 |

Age (year) |

| 11(16.1) | 68 | 1-2 | |

| 13(16.1) | 78 | > 2 | |

| 53 | 253 | Total |

Table 5: Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in buffaloes according to Provinces

| Mean ±SE | % | +ve | Samples | Sites |

| 0.21±0.04 | 20,5 | 18 | 88 | Basra |

| 0.24±0.04 | 23.7 | 23 | 97 | Dhi-Qar |

| 0.18±0.05 | 18 | 12 | 68 | Misan |

| 21 | 53 | 253 |

Total |

* significant variation at (P≤0.05)

CONCLUSION

It is concluded that buffaloes under 1 year old are more prone to sporadic pneumonic pasteurelosis and hemorrhagic septicemia caused by Pasteurella multocida. These cases with carrier animals may evolve into outbreaks similar to that occurred in marshes of south of Iraq between 2008 and 2012.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are very grateful to Dr Saba Th Musa at the Clinical Pethology Lab, Dr Eman A Mohammed, Dr Nawal D Mahmoud in the lab of zoonotic diseases/Faculty of Veterinary Medicine-University of Baghdad for their cooperation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interests are declared by authors for the contents in the manuscript.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

IAM and JMK designed the experiment, interpreted the data and wrote the draft of manuscript.IAM carried out the experiment. IAM, JMK and AJK performed the statistics and interpreted the data. AJK edited manuscript.

REFERENCES

mastitis in ewes. Large Anim. Pract. 30: 30–32.