Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences

Review Article

Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometric (GCMS) Analysis of Essential Oils of Medicinal Plants

Waseem Hassan*, Shakila Rehman, Hamsa Noreen, Shehnaz Gul, Neelofar, Nauman Ali

Institute of Chemical Sciences, University of Peshawar, Peshawar- 25120, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | Since ancient times aromatic plants had not only been used to impart flavor and aroma to food but also for their medicinal & preservative properties. Essential oils are source of numerous bioactive compounds and are commercially significant for food, household, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. Because of the mode of extraction, mostly by distillation from aromatic plants, they comprise terpenoids, terpenes, aliphatic components and phenol-derived aromatic components. Essential oils have innumerable biological activities including antiviral, antibacterial, antiparasitical, anti-inflammatory, insecticidal, antifungal, anticarcinogenic, antioxidant and antimutagenic activities. Consequently, bioactivities of essential oils have become increasingly important in the search for safe and natural alternative remedies. For the purpose the current review provides a comprehensive summary on the essential oils and their components of ninety (90) medicinal plants from more than twenty different families. Furthermore, this review covers up-to-date literatures on sources, composition, extraction techniques, characterization, general biological activities and therapeutic potentials of essential oils. The results studied in this review are aimed at attracting the attention of researchers searching for new drugs from natural products as well as those exploring the pharmaceutical diversity of essential oils.

Keywords | Medicinal plants, Essential Oils, Biological Activities

Editor | Kuldeep Dhama, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Received | June 13, 2016; Accepted | August 13, 2016; Published | August 15, 2016

Correspondence | Waseem Hassan (PhD), Institute Of Chemical Sciences, University of Peshawar, Peshawar -25120, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; Email: waseem_anw@yahoo.com

Citation | Hassan W, Rehman S, Noreen H, Gul S, Neelofar, Ali N (2016). Gas chromatography mass spectrometric (GCMS) analysis of essential oils of medicinal plants. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 4(8): 420-437.

DOI | Http://dx.doi.org/10.14737/journal.aavs/2016/4.8.420.437

ISSN (Online) | 2307-8316; ISSN (Print) | 2309-3331

Copyright © 2016 Hassan et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Essential oil can be defined as a “product obtained from natural raw material, either by distillation with water and steam, or from the epicarp of citrus fruits by mechanical processing (Schnaubelt, 1999; ISO, 2014). Similarly, other names like essence, fragrant oil, volatile oil, etheric oil, aetheroleum or aromatic oil (Başer et al., 2007) have been used to describe essential oils. Essential oils can be obtained from various aromatic plants, most commonly grown in tropical and subtropical countries. They are obtained from various parts of the plants, such as seeds, buds, leaves, roots, fruits, rhizomes, barks and flowers. Oil cells, secretary ducts, cavities or in glandular hairs are some of the prominently explored cellular sources of essential oils in plants. Among many others, Apiaceal, Lauraceae, Rutaceae, Asteraceae, Pinaceae and Cupressaceae are the well know and famous families rich in essential oil. Some of the essential oils can be found in animals sources such as musk, sperm whale, civet and can be produced by microorganism. Hydrodistillation, steamdistillation, microwave-assisted distillation, solvent extraction, cold pressing and supercritical fluid extraction (Fadel et al., 2011; Asghari et al., 2012; Mohamadi et al., 2013) are some the applied techniques used for extraction of oils.

Historically, the ancient Romans and Greeks in 1st century described the instrumental procedures for extraction (Guenther, 1948). Clear evidence which depicts the primitive form of distillation technology, which was in use in 400 BC can find in Taxila Museum, Pakistan (Sell, 2010). While In late 12th or early 13th century (1235–1311 AD), Arnald de Villanova compiled detailed information about the conventional hydrodistillation method (Sell, 2010).

Traditionally and even presently essential oils have been used for the treatment or betterment of various pathological disorders like; respiratory tract infections, colds, inhalation therapy (to treat acute and chronic bronchitis), acute sinusitis, abdominal pain, abscess, acne, fever, flu, headaches, gingivitis, bronchitis, bruises, burns, influenza, insect bites, insomnia, shock, sinusitis, sore throat, constipation, coughs, cuts, diarrhea, wounds and toothache etc. While presently, essential oils have been used in various products such as cosmetics, air fresheners, hygiene products, agriculture and food etc., (Silva et al., 2003; Hajhashemi et al., 2003; Perry et al., 2003). Approximately, 3000 essential oils are known and about 300 of which are commercially available in worldwide market (Sadgrove and Jones, 2015; Hamdy et al., 2012).

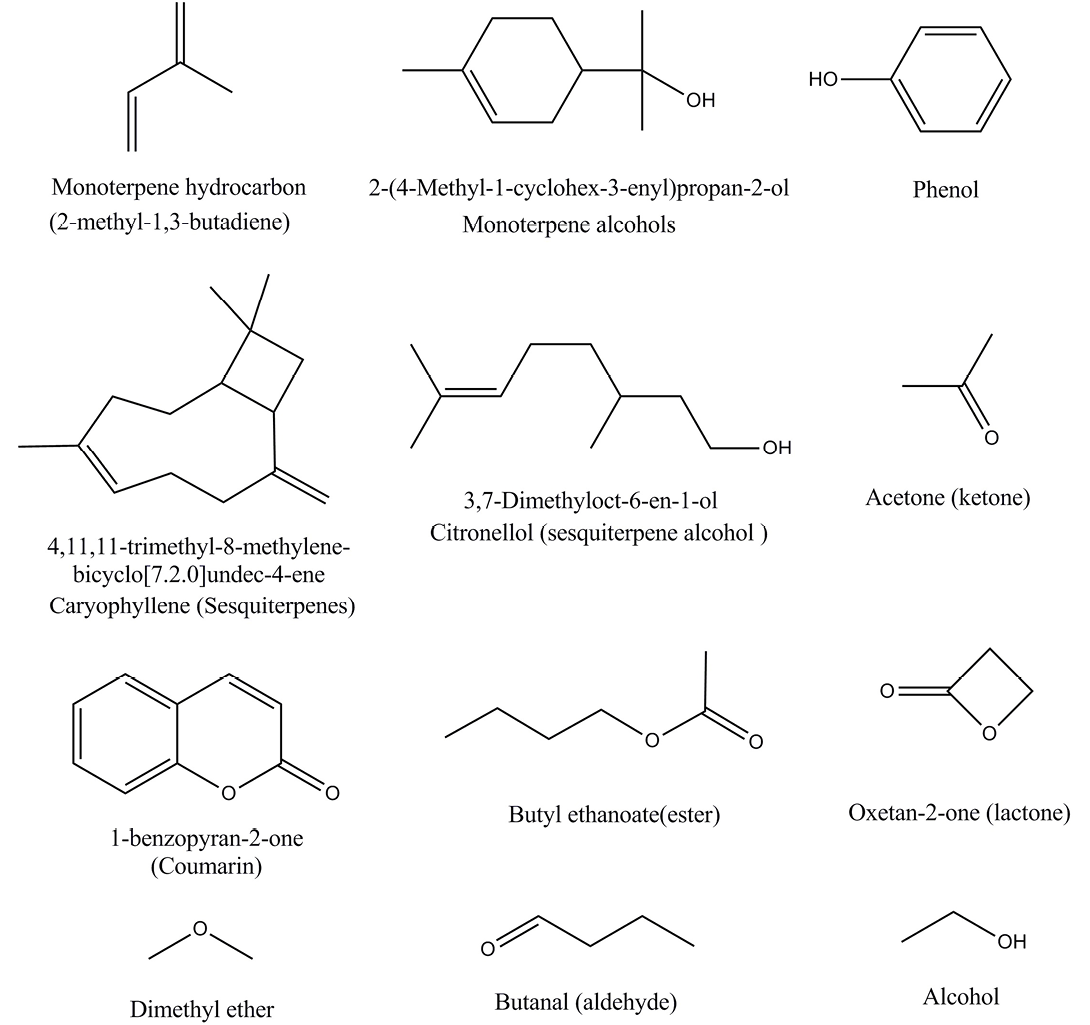

Essential oils characterization is a diverse topic and has been extensively explored in literature. For the sake of simplicity it’s worthy to note that various major organic components have been identified and the primary ones are terpene hydrocarbons, monoterpene hydrocarbons, sesquiterpenes, phenols, alcohols, oxygenated compounds, sesquiterpene alcohols, esters, lactones, ketones, coumarins, ethers, monoterpene alcohols, aldehydes and various oxides as shown in Figure 1 (Sadgrove and Jones, 2015; Hamdy et al., 2012).

Data is available which represent the antioxidant potential (Wei and Shibamoto, 2010; Tomaino et al., 2005; El-Ghorab et al., 2007, 2008; Sokmen et al., 2004; Botsoglou et al., 2004; Papageorgiou et al., 2003; Tepe et al., 2004; Candan et al., 2003; Mau et al., 2003; El-massry et al., 2006; Mimica-Dukic et al., 2004; Yanishlieva-Maslarova et al., 2001), antimicrobial properties (Hulin et a., 1998; Gutierrez et al., 2008; Bozin et al., 2006; Kelly, 1998; Burt, 2004; O’Gara et al., 2000; Santoyo et al., 2006), antifungal activity (Tripathi et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2008; Razzaghi-Abyaneh et al., 2009; Davidson and Naidu, 2000; El-Seedi, 2008; Nejad Ebrahimi, 2008; Stefanello et al., 2008; Suhr and Nielsen, 2003; Daferera et al., 2000), antiviral activity (Allahverdiyev et al., 2004; Armaka et al., 1999; Garcia et al., 2003; Edris et al., 2007), anti-inflammatory activity (Schmid-Scheonbein, 2006; Vogler and Ernst, 1999; Chithra et al., 1998; Heggers et al., 1993; Reynolds and Dweck, 1999; Shelton, 1991; Tanaka and Shibamoto, 1999), antimutagenic activity (Ramel, 1986; Odin, 1997; Kada and Shimoi, 1987; De-Oliveira, 1997; Bakkali et al., 2006), anticarcinogenic activity (Trichopoulou et al., 2000; Guba, 2000; Greenwald et al., 2001; Abdalla et al., 2007) of essential oil. Some of the miscellaneous activities like digestive activity (Sandhar et al., 2011; Meister et al., 1999; Barocelli et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2005), photo toxicity (Averbeck et al., 1990) and other activities (Muhlbauer et al., 2003; Yamaguchi et al., 1999; Aloisi et al., 2002; Ceccarelli et al., 2004; Wei Chen et al., 2004; Can et al., 2004) are also provided in detail.

It’s important to note that cytotoxicity (Knobloch et al., 1989; Sikkema et al., 1994; Helander et al., 1998; Ultee et al., 2000, 2002; Di Pasqua et al., 2007; Turina et al., 2006; Gustafson et al., 1998; Burt, 2004; Juven et al., 1994; Lambert et al., 2001; Oussalah et al., 2006), phototoxicity (Averbeck et al., 1990; Dijoux et al., 2006), nuclear mutagenicity (Andersen and Jensen, 1984; Franzios et al., 1997; Nestman and Lee, 1983; Hasheminejad and Caldwell, 1994; Goggelmann and Schimmer, 1983), cytoplasmic mutagenicity (Schmolz et al., 1999; Conner et al., 1984; Abrahim et al., 2003), carcinogenicity (Guba, 2001; Averbeck et al., 1990; Averbeckand Averbeck, 1998), antimutagenic properties (Hartman and Shankel, 1990; Sharma et al., 2001; Ipek et al., 2005; Ramel et al., 1986; De Flora and Ramel, 1988) and medicinal applications (Schwartz, 1996; Zheng et al., 1997; Ohizumi et al., 1997; Crowell, 1999; Buhagiar et al., 1999; Legault et al., 2003; Hata et al., 2003; Salim and Fukushima, 2003; Mazie`res et al., 2003; Carvalho de Sousa et al., 2004; Carnesecchi et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2004) have also been described in comprehensive details in literature.

Extraction of Essential Oils

The extraction of essential oils from phytomedicines is carried out by different methods which depend on the plant morphology. Literature exposed that extraction is a separation process that explore the quality of chemical components of essential oil from different aromatic species. Extraction must be done carefully because the significance of phytochemistry and bioactivity of essential oils is lost as a result of inappropriate extraction process. In some cases, off-odor / flavour, discoloration as well as physiological changes like the increased viscosity can also happen, which must be avoided during the extraction.

Furthermore, extraction can be performed by numerous methods including the conventional methods (steam distillation, hydro-distillation, soxhlet extraction and solvent extraction) while the unconventional techniques are pulsed electric field assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasound assisted extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, supercritical fluid extraction and pressurized liquid extraction. Although these methods have been employed since many years for essential oil extraction, their application has shown a wide range of drawbacks like low extraction efficiency, losses of some volatile compounds through hydrolytic or thermal effects, degradation of unsaturated and possible poisonous solvent residues in essential oil. Among all these oil extraction processes, solvent extraction method is selective and considered clean because it is one of the favoured separation techniques due to its elegance, speed, simplicity and applicability to both macro and tracer amounts of metal ions and bioactive compounds. Frequently this is one of the ideal methods of separating bioactive components from large amounts of medicinal plants. In addition, the process is very selective and the isolation of the constituents of essential oil can usually be made as complete by repetitions of the extraction process. Furthermore, different solvents comprising acetone, hexane, ethanol, methanol and petroleum ether can be used for extraction process (Kosar et al., 2005).

Generally, in order to abstract the essential oils the plant sample is dissolved in the solvent and then after heating it’s filtered. Consequently, the filtrate is concentrated by solvent evaporation and the concentrate is concrete (a combination of wax, fragrance and essential oil). From the concentrate, the essential oil is extracted by dissolving it in pure alcohol which alcohol absorbs the scent at low temperatures. The aromatic absolute oil is left after the vaporization of alcohol. However, this technique is time-consuming and makes the oils more expensive as compare to other techniques (Li et al., 2009).

Characterization of Essential Oils

Essential oils are complex compounds that need to characterize by different methods to confirm the consumer safety, quality and fair trade. Thus, there is a large number of instrumental techniques available such as organoleptic, physical, chemical, chromatography and spectroscopy. Furthermore, the application of processes e.g. differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), Fourier transform near-infra red (FTNIR) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy have also been studied for the isolation of chemical components of essential oil.

Literature has reported that characterization of essential oils is commonly performed by GC-MS, through which small size of essential oil constituents (volatile compounds) can be abstracted according to their boiling points. The process carried out in a long column (i.e., 30 m) which is pre-packed with a porous stationary phase that is either apolar (polymethylsiloxane) or polar wax column (polyethylene glycol). In addition, at 300 °C the essential oils is injected into the heat injection chamber leads to the precipitation of essential oil constituents in the column. The separation in gas chromatography is completed in the oven at automatic temperature ramp by gradually increasing the temperature; occasionally isothermal (constant temperature) programs are used. The separation of chemical constituents takes place by increasing the component’s individual boiling points. At this point the component vaporizes and is passed by the gas to the detector (GC-MS). The sizes and the presence of functional groups are revealed by the retention time of components in a GC-MS chromatogram. After that the separated component is fragmented by electron impact ionization, which gives a spectrum of ions which are diverted on the detector. The ions have different masses with different relative abundances. Finally, each mass spectrum is compared across a spectral library.

In present review, we focus only on five chemical constituents of the essential oils of selected plants. As plant essential oils are usually the complex mixture of natural compounds, both polar and nonpolar compounds. Generally, the constituents in essential oils are hydrogenated and oxygenated terpenes (monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes), aromatic compounds like ketones, phenols, alcohols, methoxy derivative, coumarins and terpenoids (isoprenoids) (Tongnuanchan and Benjakul, 2014). Therefore this is not possible to mention the bioactive components of 90 medicinal plants in Table 1 (given at the end).

Conclusively, a broad spectrum of literature of bioactive compounds is available for 90 medicinal plants as given in Table 1 (given at the end); therefore in this review we only focus on the five chemical components of essential oil to highlight the biological importance of medicinal plants. Besides, the review has also opened up the possibility of the use of these plants in medical and herbal preparations against different diseases.

Essential Oil Profiles of Ninety (90) Medicinal Plants

The essential oil profiles of ninety (90) medicinal plants of Pakistan (Table 1, given at the end) have obtained after a deep insight into the available literature. The collected data show that majority of the plants essential oils are composed of terpenes as their major components.

Pinenes, the bicyclic monoterpens are reported as the most abundant compounds in essential oil fraction of C. cyminum (29.2%), T. ammi (0.87%), F. vulgare (1.7%) and the second most abundant compounds in A. indica (2.04%) and W. fruiticosa (23.53%). Pinenes are known for various biological activities, such as natural insecticides, antimicrobial agents particularly against gram positive bacteria causing infectious endocarditis, play effective role against malignant melanoma and also possess antiviral activities against infectious bronchitis virus.

Beta-caryophyllene, a sesquiterpene compound constitute 33.44% of P. longum, 23.49% of P. nigrum and 36.37% of W. fruiticosa essential oil fractions while S. rebaudiana (9.6%), M. spicata (2.969%), Z. jujobe (9.16%), T. linearis (5.76%), M. piperata (2.31%) C. sativa (1.33%) and O. sanctum (26.53%) contain a comparative lower concentration of beta-caryophyllene in their total oil composition. Literature has exposed that Beta-caryophyllene is the most famous antiviral compound. Several other biological activities as anti-inflammatory, anaesthetic, anticarcinogenic, antimicrobial and insecticidal activities for beta-caryophyllene are reported in literature.

Furthermore, alcoholic terpenoids like borneol is present as major component in O. basillicum (0.20%), A. vasica (58.60%), alpha-terpineol in M. longifolia (1185.56%), C. deodara (30.2%) and menthol in A. nilotica (34.9%) essential oils. These compounds account for antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, spasmolytic, anaesthetic, balancing, tonifying and antimicrobial activities of essential oil of medicinal plants. Ketonic terpenoids such as carvone is present abundantly in M. spicata (59.40%) and C. carvi (23.3%) oils. Alpha-thujone is the main component of R. communis (31.71%) essential oil. Termerone, a sesquiterpenoide ketone constitutes the major portion of C. longa (49.04%) essential oil displayed in Table 1 (given at the end). The biological activities such as cell regeneration, neurotoxic effects, sedatives, analgesics, antiviral activities, digestive, spasmolytic and mucolytic properties have been reported for ketonic compounds of essential oils. Cymenes, myrcenes, sabinenes and limonenes catogarized as the carburemonoterpenes are found in higher concentrations in plants like C. album (40.9%), C. sativa (67.11%), V. negundo (19.04%) and C. sinensis (95.46%), respectively. The hydrocarbon monoterpenes are reported in literature with antitumour, antibacterial, stimulant, antiviral, hepatoprotective and decongestant activities. Myrcene particularly exhibit analgesic effects and an increase in sleeping time. In addition, limonene is found effective against gastric carcinogenesis, D-limonene is known to posseschemo preventive effects against hepatocarcinogenesis in mice (Uedo, 1999).

Important phenolic monoterpenes like thymol and carvacrol are reported as the chief components in essential oils of T. linearis (36.5%) and O. vulgare (18.6%) respectively. The aromatic phenol, eugenol has been reported in E. aromatica (71.56%), Z.jujobe (48.3%) and O. sanctum (43.88%) oils in higher concentrations (Table 1, given at the end). The phenol containing terpenes and aromatic compounds contribute to the spasmolytic, irritant, anesthetic, immune stimulating and antimicrobial activities of the oils (467-469). Thymol and carvacrol display potent antioxidant activities for many essential oils which contain them (Baratta, 1998). Eugenol exhibited strong antibacterial activity against infectious endocarditis. Moreover, antihelminthic, insecticidal and nematocidal activities of eugenol and antioxidative activity of both thymol and eugenol in LDL oxidation has also reported (Naderi et al., 2004).

Conclusions

The biological and pharmacological activities of essential oils are well documented and it has been suggested that the major components of the oils may be responsible for their therapeutic potentials. Highlighting this fact, the literature was reviewed for the biological activities of the most abundant essential oil constituents of the selected ninety plants. It has been observed that the activities of 90% (approx.) major components of the selected plants are reported by various researchers worldwide. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that we did not find any evidence about pronounced activities of 1-Phenyl butanone, l-Guanidinosuccinimide, maaliol, 3, 6-Dioxa-2,4,5,7-tetraoctane,2,2,4,4,5,5,7,7-Octamethyl, 1,2,3,4,5-Cyclophentanepentol, α Gingiberene and 8,11-Octadecadienic acid which are the major components of V. odorata, C. bursapestoris, V. wallichii, P. guajava, G. sylvestre, Z. officinale and B. papyrifera essential oils respectively. However it is worthy to note here that variations do occur in chemical composition of essential oils for a particular plant which may be due to various agronomic and climatic conditions, method of extraction, harvesting time and plant part used. In conclusion, this literature survey can be helpful in determining the mask potential activities of the above mentioned natural constituents, which may act as lead sources in formulation of new drugs.

Acknowledgments

Financial support of Higher Education Commission, Pakistan is cordially acknowledged and appreciated.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

authors’ contribution

All authors contributed significantly in the preparation of review.

References

Table 1: Essential Oil Profile of Ninety (90) Medicinal Plants

|

S No |

Plant Name |

Compound 1 (%) |

Compound 2 (%) |

Compound 3 (%) |

Compound 4 (%) |

Compound 5 (%) |

References |

|

1 |

Terminalia arjuna |

2-Fluro Propane (3.32) |

9-Octadecenoic acid (z),hexyl ester (4.23) |

Ethyl Benzene (5.63) |

P – Xylene (6.60) |

Norpseudoephedrine (8.42) |

(Ramesh et al., 2015) |

|

2 |

Bauhinia variegate |

1,2,3 Propanetriol 2-Propanone Hydroperoxide Triacetin Glycerol 1,2 (21.4) |

Diacetate Bicycloheptane 1,19 (2.24) |

Eicosadiene 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-(27.42) |

Ethyl ester (3.24) |

Phthalic acid (4.64) |

(Vijayalakshmi et al., 2014) |

|

3 |

Cuminum cyminum |

α-pinene (29.2) |

Limonene (21.7) |

1,8-cineole (18.1) |

Linalool (10.5) |

α-terpineole (3.17) |

(Mohammad et al., 2012) |

|

4 |

Viola odorata |

1-Phenyl butanone (22.43) |

Linalool (7.33) |

Benzyl alcohol (5.65) |

α-Cadinol (4.91) |

(4.32) |

(Hammami et al., 2011) |

|

5 |

Capsella bursa pestoris |

l-Guanidino succinimide (21.28) |

Phytol (18) |

2-Penta decanone, 6, 10, 14-tri methyl- (9.6) |

Oleic Acid (4.71) |

7-Hexa decanoic acid (22.97) |

(Yi-xia et al., 2009) |

|

6 |

Allium sativum |

Trisulfide, di-2-propenyl (46.52) |

Disulfide, di-2-propenyl (14.30) |

Trisulfide, methyl 2-propenyl (10.88) |

Diallyl disulfide (7.15) |

Octane, 4brom- (4.16) |

(Douiri et al., 2013) |

|

7 |

Mintha spicata |

Carvone (59.40) |

Limonène (6.129) |

Germacrène-D (4.665) |

1,8 cinéole (3.800) |

β-caryo phyllène (2.969) |

(Boukhebti et al., 2011) |

|

8 |

Trigonella foenum |

Palmidrol(28.72) |

Octanamide, n-(2-hydroxy ethyl) (24.47) |

Dioctyl phthalate (15.03) |

D-limonene (14.58) |

1-carvone (9.85) |

(Pande et al., 2011) |

|

9 |

Euphorbia tirucalli |

Campesterol (1.06) |

Eupho (25.6) |

b-Amyrin (6.15) |

Glutinol (17.1) |

b-sitosteroln (14.4) |

(Uchida et al., 2010) |

|

10 |

Cyperus rotundus |

5-oxo-isolongifolene (16.268) |

α-gurjunene (10.219) |

(z)-Valerenyl acetate (8.888) |

α-Salinene (4.480) |

Valerenic acid (3.669) |

(Bisht et al., 2011) |

|

11 |

Saussureae lappa |

Dehydrocostus lactone (46.75) |

Costunolide (9.26) |

8-cedren-13-ol (5.06) |

α-curcumene (4.33) |

(Liu et al., 2011) |

|

|

12 |

Solanum nigrum |

Germacrene D (14.8) |

Pentadecanal (11.4) |

β-Elemene (10.1) |

α-Bulnesene (7.9) |

δ-Cadinene (6.0) |

(Akintayo et al., 2013) |

|

13 |

Zizyphus jujoba |

Eugenol (48.3) |

Isoeugenol (11.83) |

Caryophyllene (9.16) |

Eucalyptol (3.27) |

Caryophyllene oxide (3.14) |

(Al-Reza et al., 2010) |

|

14 |

Eugenia aromatica |

Eugenol (71.56) |

Eugenyl acetate (8.99) |

Caryophyllene oxide (1.67) |

Nootkatin (1.05) |

Phenol-4- (2, 3-dihydro-7- methoxy- 3- methyl5- (1- propenyl)-2- benzofurane (0.98) |

(Nassar et al., 2007) |

|

15 |

Glycyrrhiza glabra |

Ethylenimine (1.57) |

Methacrylo nitrile (9.69) |

2-Propene nitrile, 2-methyl (7.86) |

Linalool (2.25) |

Aspartic acid (1.44) |

(Chouitah et al., 2011) |

|

16 |

Piper longum |

β-caryophyllene (33.44) |

3-carene (7.58) |

Eugenol (7.39) |

d-limonene (6.70) |

Zingiberene (6.68) |

(Liu et al., 2007) |

|

17 |

Crocus sativus |

Catechol (5.19) |

Vanillin (8.24) |

Salicylic acid (7.98) |

Cinnamic acid (8.56) |

Gentisic acid (2.94) |

(Esmaeili et al., 2011) |

|

18 |

Piper nigrum |

β-caryophyllene (23.49) |

3-carene (22.20) |

d-limonene (18.68) |

β-pinene (8.92) |

α-pinene (4.03 ) |

(Liu et al., 2007) |

|

19 |

Tagetes minuta |

Trans-tagetenone (32.3) |

Cis-tagetenone (20.9) |

Dihydrota getone (9.7) |

Trans-pino carvyl acetate (7.1) |

Carvone (4.3) |

(Vázquez et al., 2011) |

|

20 |

Thymus linearis |

Thymol (36.5) |

Carvacrol (9.50) |

Thymyl acetate (7.30) |

β-caryophyllene (5.76) |

(Hussain et al., 2013) |

|

|

21 |

Carum carvi |

Carvone (23.3) |

Limonene (18.2) |

Germacrene D (16.2) |

Trans-dihydro- carvone (14.0) |

Carvacrol (6.7) |

(Iacobellis et al., 2005) |

|

22 |

Mentha piperata |

Linalool (51.0) |

Carvone (23.42) |

3-octanol (10.1) |

Terpin-4-o (8.00) |

Trans-caryophylline (2.31) |

(Sartoratto et al., 2004) |

|

23 |

Nigella sativa |

Trans-Anethole (27.1) |

Thymoquinone (11.8) |

p-Cymene (9.0) |

Longifolene (5.7) |

Limonene (4.3) |

(Gerige et al., 2009) |

|

24 |

Acacia nilotica |

Menthol (34.9) |

Limonene (15.3) |

- |

- |

- |

(Ogunbinu et al., 2010) |

|

25 |

Adhatoda vasica |

Borneol (58.60 ) |

Bicyclo[jundec-4-ene, 4, 11-trimethyl- 8 -Methylene (14.56) |

2, tert 1-butyl-1,4-dimethoxy benzene (6.50) |

1,1,4a trimethyl-5,6-dimethylenedecahydro naphthalene (5.28) |

Ethano naphthalene (2.82) |

(Sarker et al., 2011) |

|

26 |

Psidiumg uajava |

3, 6-Dioxa-2, 4, 5, 7-tetraoctane, 2, 2, 4, 4, 5, 5, 7, 7- Octamethyl (11.67) |

Cyclononane (10.66) |

Pyridazin-3(2H)-one, 4-amino-5-chloro-2-phenyl (9.35) |

Pyridazin-3 (2H)-one, 4- diacetylamino-5- chloro-2- Phenyl (7.35) |

N-Methylrhodanine (5.01) |

(Aponjolosun et al., 2011) |

|

27 |

Cassia fistula |

(E)-nerolidol (38.0) |

2-hexadecanone (17.0) |

- |

- |

- |

(Tzakou et al., 2007) |

|

28 |

Cannabis sativa |

Beta-myrcene (myrcene) (67.11%) |

Limonene (cinene, nesol, cajeputene) (16.38) |

Linalool (beta-linalool, linalyl alcohol) (2.80%) |

Beta-caryophyllene (1.33) |

a-pinene (pinene, 2-1 (1.11) |

(Ross et al., 1996) |

|

29 |

Allium cepa |

Dimethyl-trisulfide (16.64) |

Methyl-propyl-trisulfide (14.21) |

Methyl- (1-pro penyl)-disulfide (13.14) |

Diallyl-disulfide (28.05) |

Diallyl-trisulfide (33.55) |

(Kocić‐Tanackov et al., 2012) |

|

30 |

Phoenix dactylifera |

Oleic (49.8) |

Lauric (13.1) |

Myristic (11.5) |

Palmitic (11.3) |

Linoleic (8.9) |

(Al‐Shahib et al., 2003) |

|

31 |

chenopodium album |

p- cymene (40.9 ) |

Ascaridole (15.5 ) |

Pinane-2-ol (9.9 ) |

α-pinene (7.0 ) |

β-pinene (6.2 ) |

(Negi et al., 2013) |

|

32 |

Abutilon indicum |

- |

9,12-Octa decadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)- (11.7227) |

Linolenin, 1-mono- (13.6683) |

Vitamin E (11.8398) |

2,2,4- Trimethyl- 3- (3, 8 ,12 ,16 tetramethyl- hepta deca- 3, 7, 11, 15-tetra enyl) -cyclo hexanol (7.9571) |

(Ramasubramaniaraja et al., 2011) |

|

33 |

Zanthoxylum armatum |

Bornyl acetate (16.61-22.66) |

Cymene (8.25-12.50) |

á-copaene (7.54-7.59) |

á-copaene (7.54-7.59) |

Camphene (4.32-4.66) |

(Usman et al., 2010) |

|

34 |

Citrus limon |

Limonene (65.65 ) |

b-pinene (11.00) |

g-terpinene (9.01) |

a-pinene (1.88) |

Sabinene (1.05) |

(de Rodríguez et al., 1998) |

|

35 |

Sida cordifolia |

Ephedrine (68.27) |

Vasicinol (20.99) |

Hypaphorine (3.97) |

Vasicinone (3.97) |

(Joseph et al., 2011) |

|

|

36 |

Corriandrum sativum |

2-decenoic acid (30.8) |

E-11-tetra decenoic acid (13.4) |

Capric acid (12.7) |

Undecyl alcohol (6.4) |

Tridecanoic acid (5.5) |

(Bhuiyan et al., 2009) |

|

37 |

Ricinus communis |

alpa-thujone (31.71) |

1,8-cineole (30.98) |

alpa-pinene (16.88) |

Camphor (12.98) |

Camphene (7.48) |

(Kadri et al., 2011) |

|

38 |

Lepidium sativum |

Behinic acid (36.617) |

Arachidonic (25.611 ) |

Linoleic (14.651) |

Palmitic (11.249) |

Lauric (7.315) |

(Ottai et al., 2012) |

|

39 |

Sesamum indicum |

Flavonol (13.16) |

Anthraquinone (9.86) |

Hexadecanolicacid, methyl ester (6.27) |

Ketopinic acid (8.9) |

Stigmasterol (4.82) |

(Sharma et al., 2012) |

|

40 |

Curcuma longa |

ar-turmerone (49.04) |

Humulene oxide (16.59) |

Beta-selinene (10.18) |

Caryphyllene oxide (5.60) |

Alpa-Humulene (3.41) |

(Tsai et al., 2011) |

|

41 |

Grewia asiatica |

1,2-epoxy- 184 (5.618) |

1-(2,cyano-2-ethyl butyl)3-isopropyl urea 225 (5.935) |

Hexadecanoic acid 270 (6.260) |

- |

- |

(Rehman et al., 2013) |

|

42 |

Valeriana wallichii |

Maaliol (36.8) |

Beta-gurjunene (21.3) |

Acoradiene (9.9) |

Guaiol (8.6) |

Alpha-santalene (5.5) |

(Sah et al., 2012) |

|

43 |

Tribulus terrestris |

α-Amyrin (65.73%) |

1,2-Benzene dicarboxylic acid, diso octylester (9.27) |

n- hexadecane oicacid (8.83) |

Octadecanoic acid (2.95) |

Phytol (0.99) |

(Abirami et al.., 2011) |

|

44 |

Origanum vulgare |

Carvacrol (18.06) |

Thymol (7.36) |

Gamma-terpinene (5.25) |

p-cymene (5.02) |

Limonene (4.68) |

(Derwich et al., 2010) |

|

45 |

Datura stromium |

Oleic acid Methyl ester (22.760) |

Elaidic acid methyl ester (21.866) |

Alpha- Linolenicacid methyl ester (10.321) |

Palmitoleic acid methyl ester (8.559) |

Gondoic acid methyl ester (5.767) |

(Koria et al., 2012) |

|

46 |

Swertia chirata |

Undecanoic acid (28.63) |

2-buten-2-one (20.42) |

Camphor (18.40) |

2-Hepta decanone (14.72) |

Cedrol (13.07) |

(Kyong-Su et al., 2006) |

|

47 |

Punica granatum |

Nitroisobutyl glycerol (19.02) |

Ethyl, alpha-d-glucopyranoside (12.65) |

3,5-Dihydroxy-6-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyran-4-one (11.83) |

Maltol (9.46) |

4-deuterio-transs-3, 4-dihydroxy-cyclopentene (9.41) |

(Zab et al., 2012) |

|

48 |

Cedrus deodara |

α-terpineol (30.2) |

Linalool (24.47) |

Limonene (17.01) |

Anethole (14.57) |

Caryophyllene (3.14) |

(Zeng et al., 2012) |

|

49 |

Hippophaë rhamnoides (mg/100 g) |

Clerosterol (14.3) |

Lanosterol (tr) + sitosterol (787.4) |

b-Amyrin + sitostanol (122.5) |

A stigmastadienol + a-amyrin (81.4) |

Erythrodiol + citrostadienol (67.5) |

(Li et al., 2007) |

|

50 |

Mentha longifolia |

α-Terpineol (1185.56 ) |

Sabinene (968.27 ) |

β-pinene (970.24) |

β-Myrcene (989.05 ) |

3- octanol (994.09 ) |

(Saeidi et al., 2012) |

|

51 |

Juglans regia |

α-Thujene (0.50) |

p-Cymene (10.94) |

1,8-Cineol (0.67) |

Linalool (1.07) |

Carvacrol (1.59) |

(Abbasi et al., 2010) |

|

52 |

Plantago ovata |

Hexanoic acid (0.11) |

2-Amylfuran (0.11) |

n-Decane (0.08) |

Nonanal (0.09) |

Cycloheptanemethanol (0.12) |

(Seifi et al., 2014) |

|

53 |

Berberis lycium |

Oleic acid (39.67±0.61) |

Palmitoleic |

- |

- |

Oleic acid (39.67±0.61) |

(Asif et al., 2007) |

|

54 |

Withania somnifera |

Undecanoic Acid (1.30) |

Dodecanoic Acid (0.47) |

Octanoic Acid (0.84) |

IH-Indole (23.64) |

Cyclopentane, 1-methyl-3- (2-methyl propyl) -(11.07) |

(Kumar et al., 2011) |

|

55 |

Dalbergia sisso |

2-Propanamine (3.03) |

Pentanal (2.29) |

Guanosine (2.02) |

Acetaldehyde (1.47) |

Cyclobutanol (0.47) |

(Aly et al., 2013) |

|

56 |

Pyrus pyrifolia |

1-Hexanol (1.5) |

Hexanal (35.8) |

Nonanal (0.3) |

Ethyl hexanoate (0.6) |

2-Octanone (0.3) |

(Li et al., 1991) |

|

57 |

Vernonia amygdalina |

Caryophyllene pxide (2.31) |

Guaiol (1.75) |

n-Hexadeca dienoic acid (42.88) |

Squalene (11.31) |

Octadecanoic acid (4.41) |

(Abirami et al.., 2011) |

|

58 |

Trachyspermum ammi |

Pinene (0.87) |

Camphene (0.10) |

Myrcene (0.48) |

Terpine-4-ol (0.32) |

Thymol (41.77) |

(Park et al., 2007) |

|

59 |

Carica papaya |

Oleic acid (45.97) |

Stearic acid (8.52) |

Caprylic acid (0.06) |

Pelargic acid (0.11) |

Myristic acid (0.51) |

(Pérez- Gutiérrez et al., 2011) |

|

60 |

Citrullus colocynthis |

Toluene (1.692) |

Nonane (1.184) |

Ethylbenzene (0.237) |

Undecane (15.348) |

Dodecane (0.120) |

(Tanveer et al., 2012) |

|

61 |

Azadiracht a indica A. Juss |

Hexanal (1.15) |

a-Pinene (2.04) |

Limonene (3.34) |

Myrcene (0.59) |

n-Undecane (6.31) |

(Wafaa et al., 2007) |

|

62 |

Raphanus sativus |

Palmitic acid (22.92) |

Lignoseric and myristic acids (8.55) |

Oleic acid (13.06) |

- |

- |

(Wahab et al., 2007) |

|

63 |

Tamarindus indica |

1-Octanoate (0.3) |

Nonanoic acid (1.92`) |

n-Tridecanoic (1.2) |

n-Eicosenoate (0.91) |

n-Docosanoate (1.00) |

(Khanzada et al., 2008) |

|

64 |

Pisum sativum L |

Palmitic acid (30) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

(Taha et al., 2011) |

|

65 |

Foeniculum vulgare |

α-Pinene (1.7) |

Limonene (2.7) |

p-Cymene (0.1) |

Fenchone (18.8) |

Methyl chavicol (3.3) |

(Radulović et al., 2010) |

|

66 |

Morus alba |

Formic acid,1-methylethyl ester (25.46) |

n-Pentanal (2.76) |

Propene 3,3,3-D3 (9.81) |

Benzyl benzoate (23.94) |

Benzeneethanamine, 2-fluoro- beta (6.41) |

(Salem et al., 2013) |

|

67 |

Moringa oleifera |

Hexadecanoic acid (9.90) |

Docosanoic acid (7.24) |

Eicosanoicacid(5.81) |

Pentadeconic acid (55.60) |

Tetracosanoic acid (3.78) |

(Gaikwad et al., 2011) |

|

68 |

Ipomoea batatas |

Pyridine (10) |

Xylene (1) |

2-Furan carboxaldehyde (2) |

2,3-Pentanedione (10) |

Limonene (10) |

(Wang et al., 2000) |

|

69 |

Taraxacum officinale |

Sesquiterpenes (55.6) |

Momoterpene (33.3) |

- |

- |

- |

(Otsuka et al., 2010) |

|

70 |

Ocimum sanctum |

Eugenol (43.88) |

Caryophyllene (26.53) |

Cyclopentane, cyclopropylidene (1.02) |

Benzene methanamine (2.04) |

Octadecane, 1,1-dimethoxy (2.04) |

(Devendran et al., 2011) |

|

71 |

Ocimum basillicum |

Broneol (0.20) |

Napthalene (0.53) |

α-Cubene (3.85) |

Eugenol (61.76) |

Vanillin (1.27) |

(Dev et al., 2011) |

|

72 |

Acorus calamus |

B Asarone (71.51) |

9,12-Octadeca dienoicacid (16.00) |

n-Hexa decanoic acid (5.23) |

Shyobunone (2.11) |

A Asarone (1.83) |

(Kumar et al., 2010) |

|

73 |

Mangifera indica |

Terpinolene (62.4) |

3-Carene (9.5) |

Limonene (6.8) |

Myrcene (5.1) |

p-Cymen-8-ol (4.3) |

(Andrade et al., 2000) |

|

74 |

Gymnema sylvestre |

1,2,3,4,5-Cyclo phentanepentol (47.83) |

Oleic Acid (13.20) |

n-Hexa decanoic acid (12.81) |

Heptanediamide, N,N’-di-benzoyloxy (3.77) |

Benzene, (ethenyloxy) (3.11) |

(Thangavelu et al., 2012) |

|

75 |

Eclipta prostrate |

Heptadecane (14.78) |

6,10,14-trimethyl-2-pentadecanone (12.80) |

n-hexa decanoic acid (8.98) |

Pentadecane (8.68) |

Octadec-9-enoic acid (3.35) |

(Tahrouch et al., 1998) |

|

76 |

Peganum harmala |

3,Octanone (19.2) |

Propylic acid (11.5) |

N. Formyl aniline (9.1) |

B. Ionone (8.1) |

6-methyl-2-propylpyrimidone (5.1) |

(Huang et al., 2012) |

|

77 |

Vites negundo |

Sabinene (19.04) |

Caryophyllene (18.27) |

Eremophilene (12.76) |

Caryophyllene oxide (11.33) |

β-Terpinyl acetate (8.99) |

(Kaur et al., 2010) |

|

78 |

Zingiber officinale |

α Gingiberene (20.57) |

β-Seiquphell andrene (12.71) |

α Curcumen (11.27) |

Cyclo Hexane (10.61) |

α Fernesene (9.77) |

(Setty et al., 2011) |

|

79 |

Woodfordia fruiticosa |

β-Caryophyllene (36.37) |

α-pinene (23.53) |

γ-curcumene (7.76) |

Caryophylleneoxide (6.95) |

2,6-Dimethyl-1,3,5,7- Octa tetraene (6.79) |

(Kaur et al., 2010) |

|

80 |

Chenopodium ambrosoides |

α-Terpinene (51.3) |

p-Cymene (23.4) |

p-Mentha-1,8-diene (15.3) |

Isoascaridole (5.1) |

Limonene (0.9) |

(Chekem et al., 2010) |

|

81 |

Cynodon dactylon |

Glycerin (38.49) |

9,12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)- (15.61) |

Hexadecanoicacid, ethyl ester (9.50) |

Ethyl à-d-glucopyranoside (8.42) |

Linoleic acid ethyl ester (5.32) |

(Jananie et al., 2011) |

|

82 |

Euphorbia hirta |

1,6,10,14-Hexadecatetraen-3ol, 3, 7, 11, 15-tetramethyl-, (E,E) (58.88) |

Phytol (13.61) |

Diazo progesterone (8.88) |

3,5-Dimethyl-5-hexen-3-ol (5.03) |

Vitamin-E (4.73) |

(Suresh et al., 2012) |

|

83 |

Broussonetia papyrifera |

8,11-Octa decadienic acid (79.17) |

Palmitic acid (10.77) |

Oleic acid (5.51) |

Stearic acid (3.04) |

8-Octadecenoic acid (1.00) |

(Zhao et al., 2011) |

|

84 |

Urtica dioica |

2,6,10-trimethyl,14-ethylene-14-pentadecne (19.96) |

2,6,10,15-tetramethylheptadecane (12.82) |

Heptadecyl ester (9.45) |

Hexyl octyl ester (6.31) |

2,7,10-trimethyldodecane (5.60) |

(Dar et al., 2012) |

|

85 |

Mucuna prurians |

n-Hexadecanoic acid (48.21) |

Squalene (7.87) |

Oleic acid (7.62) |

9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-(6.21) |

Hexanedioic acid, bis (2-ethylhexyl) ester (4.05) |

|

|

86 |

Tinospora cordifolia |

Fructose (36.49) |

Arabinose (18.34) |

Glucose (13.22) |

Myo- inositol (5.4) |

Mannose (4.71) |

(Sharma et al., 2012) |

|

87 |

Stevia rebaudiana |

Nerolidol (17.1) |

Benzyl alcohol (13.8) |

δ-cadinene (8.9) |

Caryophyllene (6.9) |

Caryophyllene oxide (6.5) |

(Moussa et al., 2005) |

|

88 |

Ziziphus mauritiana |

Hexadecanoic acid (16.3) |

Octanoic acid (6.3) |

D-ribofuranose (6.3) |

Hexanoic acid (6.2) |

Heptanoic acid (4.6) |

(Memon et al., 2012) |

|

89 |

Citrus sinensis |

Limonene (96.46) |

Beta – Myrcene (2.13) |

Alpha – Pinene (0.51) |

Decanal (0.12) |

Sabinene (0.09) |

(Tan et al., 2011) |

|

90 |

Mimosa pudica |

1,3,5-Cycloheptatriene (1.2805) |

4-Pentenal, 2-methyl (0.4907) |

p-Xylene (2.2758) |

2-Cyclopentene-1,4-dione (0.2023) |

Heptanal (1.4223) |

(Ramesh et al., 2014) |