Optimizing Agricultural Growth: Targeted Farm Credit Allocation Strategies for Sustainable Crop Yields in Pakistan

Research Article

Optimizing Agricultural Growth: Targeted Farm Credit Allocation Strategies for Sustainable Crop Yields in Pakistan

Rehmat Ullah, Riaz Ahmed*, Muhammad Tahir, Abdul Majid Nasir and Mushtaq Muhammad

Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Turbat, Turbat, Pakistan.

Abstract | This study explores the correlation between the distribution of farm credit and the yields of major crops in Pakistan. The study used multiple regression model for investigating how various forms of farm credit relate to crop yields across different crop categories using district-level data from 2010 to 2020. The study findings reveal that small-scale farm credit emerges as a potent driver that significantly boosted the production of food crops, cash crops, pulses, and oilseeds during the study period. A 10 percent increase in small-scale farm credit resulted in substantial production gains ranging from 1.44 to 5.98 percent across these crops. Medium-scale farm credit also exhibited a positive association, notably enhancing yields of food crops, cash crops, and oilseeds by 2.61, 7.49, and 3.61 percent respectively. However, the study uncovers a relatively weak positive relationship between large-scale farm credit and crop production. These findings suggest that a significant portion of farm credit should be allocated to small and medium farm owners. Also, the current policy of the State Bank of Pakistan—which allocates about 90 percent of agricultural farm credit to small and medium farmland owners—aligns perfectly with the findings of this study. This policy should be maintained with a robust monitoring mechanism to ensure the effective allocation and utilization of funds.

Received | December 01, 2023; Accepted | July 19, 2024; Published | October 28, 2024

*Correspondence | Riaz Ahmed, University of Turbat, Pakistan; Email: riaz.ahmed@uot.edu.pk

Citation | Ullah, R., R. Ahmed, M. Tahir., A.M. Nasir. and M. Muhammad. Optimizing agricultural growth: targeted farm credit allocation strategies for sustainable crop yields in Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 40(4): 1344-1353.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2024/40.4.1344.1353

Keywords | Farm credit, Crop yield, Agricultural productivity, Food security, Sustainable finance

Copyright: 2024 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Hunger remains a formidable global challenge; as of July 2024, 309 million people in 72 countries face daily food insecurity with a staggering 42.3 million on the brink of starvation (World Food Programme, 2024). Developing nations have potential to generate sufficient food supplies to cater their burgeoning populations while alleviating poverty (Schultz, 1980). For this purpose, sustainable investment in the agricultural sector is one of the most effective strategies that can combat poverty and ensure food security in rural regions (Bulman et al., 2021). An essential component of this strategy is the provision of agricultural/farm credit to farmers. These credits play a pivotal role in enhancing the capabilities of small and medium-scale farm owners and consequently reduce poverty in rural areas (Webb and Kennedy, 2014). Developing nations can strengthen their overall economic growth and meet the increasing demand for food through resilient and enduring agricultural systems by prioritizing sustainable agricultural production practices in their economies (Rockström et al., 2017).

The agricultural sector constitutes a significant driver of economic growth in many developing countries that contribute about a quarter of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Tiffin and Irz, 2006; Sertoglu et al., 2017). In particular, Pakistan hugely depends on its agriculture sector; with over two-thirds of the population is dependent on this sector for their livelihood. More specifically, the sector contributes about 19 percent of the country’s GDP and employs over 38 percent of the nation’s workforce (Government of Pakistan, 2021). However, the share of the agricultural sector in the country’s GDP has steadily declined; plummeting from about 50 percent in the 1950s (Raza and Siddiqui, 2014) to a mere 19.4 percent in 2020 (Government of Pakistan, 2021). The factors contributing to this decline include decline antiquated farming practices, a lack of credit access, and the absence of critical inputs like seeds and fertilizers (Government of Pakistan, 2000).

Despite its heavy reliance on agriculture in terms of employment, exports, and rural population, Pakistan continues to grapple with low agricultural productivity compared to many other developing economies globally (The Institute of Bankers Pakistan, 2022). The overarching purpose of this study is to investigate the heterogeneous association of farm credit with the productivity of various type crops in an agro-based developing economy—focusing Pakistan as a case study.

In order to invest in sustainable agricultural production with maximum efficiency and minimal resource input, agriculture credit to farmers emerges as one of compelling solution. Which empowers farmers to embrace modern agricultural technologies, procure contemporary equipment and essential inputs and, in turn, achieve better returns within the agricultural sector (Zulfiqar et al., 2021; Chandio and Jiang, 2018; Raza et al., 2023). The critical impediments to agricultural sector growth and development highlighted in literature include but not limited to the adoption of appropriate agricultural technology, research and development, capacity building of farmers, bureaucratic hurdles in credit processing, high interest rates and the fragmentation of land holdings among farmers (Johnston and Mellor, 1961; Chandio and Jiang, 2018; Saqib et al., 2018; Agbodji and Johnson, 2019; Raza et al., 2023).

The existing literature explored the relationship between agricultural credit and agricultural productivity broadly within the context of emerging economies that are heavily reliant on the agriculture sector. For examples, Chisasa and Makina (2013) have established positive correlations between agricultural credit, capital formation, and agricultural productivity while Bekun et al. (2018) and Udoka et al. (2016) have unveiled significant and positive associations between agricultural credit and agricultural growth in Nigeria. Prior research in Pakistan by Bashir et al. (2007; 2009) has identified a positive and significant association of bank credit with sugarcane and wheat production, respectively, in the Faisalabad district. Similarly, Chandio et al. (2015) have examined the relationship between maize productivity and agricultural credit in Pakistan. Additionally, Zulfiqar et al. (2021) have scrutinized credit access determinants in the southern part of Punjab province, while Saqib et al. (2018) have probed factors influencing farmers’ livelihoods and access to bank credit in flood-prone areas of Pakistan.

Existing literature predominantly have explored the relationship between agricultural finance and production at either macro (i.e. the country level) or micro (i.e. the crop level) levels. However, due to substantial regional variation within a country, these findings at these two extremes fail to provide adequate insights to the policymakers for formulating sustainable financing policies at the national level. Consequently, the purpose of this study is to bridge this gap in the literature by investigating the correlation between farm credit and crop production at the mezzo (i.e. the district level) level in Pakistan. To facilitate a comprehensive analysis of this relationship, the study uses sixteen main crops categorized into four groups (food crops, cash crops, pulses, and oilseeds) and three categories of farm credit (small, medium, and large-scale farm credit) across almost all districts of Pakistan. The central research question guiding this study is as follows: What is the impact of farm credit on crop production in Pakistan? The study’s primary objective is to assess credit rationing’s implications on sustainable agricultural financing by identifying and exploring credit rationing among small, medium, and large-scale farm holders in the production of various crops in Pakistan.

Materials and Methods

Data sources

This study utilizes secondary data collected from various reputable sources, including publications and official records of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), Agriculture Marketing Information Services (AIMS), Agriculture Departments of Provincial Governments, and the Ministry of National Food Security and Research. The unit of analysis in this study is a crop within a district. Data for the variables of interest, such as farm credit and crop yield, are aggregated at the district level. The data covers the period from 2010 to 2020.

Measurement of variables

The study focuses on two main variables: agricultural crop yield and farm credit. Agricultural crop yield, denoted as the unit of production of crops divided by the area in hectares, is calculated based on the methodology established by Poudel et al. (2014) and Wineman et al. (2019). The study covers sixteen major crops grouped into four crop categories: food crops (rice, wheat, maize, jowar, bajra, and barley), cash crops (cotton, sugarcane, tobacco, and guar-seed), pulses (mash, lentil, moong, and gram), and oilseeds (rapeseed/mustard seeds and sesame seeds).

Table 1. Types of farm credit.

|

Provinces |

Small-Scale Farm credit (SSFC) |

Medium-Scale Farm credit (MSFC) |

Large-Scale Farm credit (LSFC) |

|

Punjab |

0-12.5- acres |

Above 12.5-50 acres |

Above 50 acres |

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

0-12.5- acres |

Above 12.5-50 acres |

Above 50 acres |

|

Sindh |

0-16 acres |

Above 16-64 acres |

Above 64 acres |

|

Balochistan |

0-32 acres |

Above 32-64 acres |

Above 64 acres |

|

Distribution of Credit |

|||

|

Agricultural credit scheme |

70 percent |

20 percent |

10 percent |

Note: Small scale farm credit, medium scale farm credit and large-scale farm credit are alternatively called subsistence holding loans, economic holding loan, and above economic holding loan as per SBP definition. Source: SBP, 2022.

The independent variable ‘farm credit’ in this study encompasses production loans for agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilizers, farm development loans, and loans for the acquisition of farm machinery and equipment, excluding non-farm loans (State Bank of Pakistan, 2022). The farm credit data is categorized into short-term credits (up to 18 months), medium-term credits (1.5 to 5 years), and long-term credits (5 to 7 years), with specific allocations for Small-Scale Farm Credit (SSFC), Medium-Scale Farm Credit (MSFC), and Large-Scale Farm Credit (LSFC) based on landholding types across provinces (see Table 1. for further details). The crop yield and farm credit data from all 114 districts for the period between 2010 and 2020 are used to examine the relationship between farm credit and agricultural yield.

Other control variables at the district level include the Human Development Index (HDI), Population Density, and Rural Population. District-level HDI data is sourced from the Pakistan Human Development Index Report 2017 by UNDP Pakistan, while population density and rural population data are obtained from the 2017 population census conducted by

the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. To address omitted variable bias, this study includes crop-fixed effects,

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

|

Variables |

Obs. |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min. |

Max. |

|

Agricultural yield (in KGs/Hectares) |

17,080 |

3,067 |

10,760 |

0 |

113,674 |

|

Farm credit (in PKR) |

17,080 |

3,084 |

8,982 |

0 |

155,455 |

|

Small Scale Farm credit (in PKR) |

17,080 |

1,335 |

2,132 |

0 |

17,390 |

|

Medium Scale Farm credit (in PKR) |

17,080 |

574 |

871 |

0 |

5,031 |

|

Large Scale Farm credit (in PKR) |

17,080 |

1,176 |

7,578 |

0 |

138,062 |

|

HDI |

114 |

0.56 |

0.19 |

0.17 |

0.88 |

|

Population Density (number of people/areas in square kilometer) |

114 |

547 |

805 |

4 |

6279 |

|

Rural Population (in percentage) |

114 |

76.42 |

15.78 |

0 |

100 |

Note: The unit of analysis is each individual crop i within district d during year t. The dataset comprises 16 different crops, spanning 114 districts of Pakistan, and covers an 11-year period from 2010 to 2020. To control for district-level variation, the latest Human Development Index (HDI) from 2015, population density, and rural population data from 2017 are utilized. Crop-type (4 crop types) -, province (4 provinces) -, and year (11 years)-fixed effects are employed to account for other district level and temporal variation over the study period. Source: Authors ‘own calculation based on data on various sources given in data section.

province fixed effects, and year-fixed effects to control for variations at the crop, provincial, and temporal levels. These effects account for factors such as yield disparities among districts, climate and geographic conditions, market dynamics, governmental policies, and temporal fluctuations.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics, presented in Table 2, provide an overview of the variables under consideration. On average, a district produces approximately 3000 kilograms of agricultural crops per hectare of cultivated land. The State Bank of Pakistan disburses farm credit, with an annual average of Rs. 3,084 to farmers in a district, distributed among small, medium, and large-scale farming. Districts exhibit varying HDI scores, ranging from 0.17 to 0.88, with an average HDI of 0.56. Additionally, our sample data reveals an average population density of 547 individuals per square kilometer, with 76 percent residing in rural areas.

Estimation model

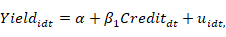

The study explores the relationship between agricultural crop yield and farm credit, incorporating various influencing factors. The empirical model is defined as follows:

where Yieldidt represents the ith crop yield (productivity) in district d and year t which is the crop production in units divided by the covered area of land in hectare. Creditdt is the farm credit in d district for year t, provided to farmers by commercial banks and financial institutions through target sets by the SBP. We include farm credit as an explanatory variable in the production function, following the argument made by (Carter, 1989). According to Carter, agricultural credit influences agriculture productivity in three ways. First, it promotes efficient resource allocation by removing barriers to purchasing inputs and using them efficiently. As a result, farmers use a more profitable combination of inputs. Second, when farm credit is used to acquire new technology, such as high-yielding seeds and expensive inputs, it not only brings farmers closer to maximum productivity but also improves overall efficiency, leading to increased productivity. Finally, farm credit can also promote the use of fixed resources such as land and family labor due to its effects on household consumption and productivity. This, in turn, increases management efficiency and profitability. In short, Carter’s argument suggests that farm credit has a significant impact on managerial efficiency, resource allocation, and overall profitability in agriculture.

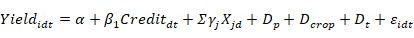

The expanded model includes additional control variables and fixed effects to better capture the complexities of the relationship. It’s now given by:

The j control variables Xjd such as HDI, population density, and rural population percentage are included to account for district-level variations that could impact crop yield. The coefficients γj indicate how these variables affect crop yield independently. Provincial fixed effects (Dp) and crop fixed effects (Dcrop) control for differences across provinces and crop types that might affect crop yield. These fixed effects capture unobserved factors specific to each province and crop. The time dummy variable (Dt) captures time-specific effects that could influence crop yield but are constant across all districts. The error term (Eidt) represents unobserved factors and random disturbances that affect crop yield but are not accounted for by the included variables.

The model employs logarithmic transformations for both crop yield and farm credit, facilitating the interpretation of percentage changes in crop yield concerning percentage changes in farm credit. Parameters are estimated by using the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) technique taking the unbalanced panel data (i.e., individual crop i within district d during year t) with crop-type, province and year fixed effects in STATA 12.

Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the results and discuss the implications of our study on the relationship between farm credits and agricultural yield at a district level in an economy primarily dependent on agriculture. To account for district-level variations, we incorporated control variables such as the Human Development Index (HDI), population density, and the percentage of rural population alongside fixed effects for crop-types, provinces, and years. To mitigate the problem of multicollinearity among the independent variables

Table 3. Regression Analysis: Relationship between farm credit and agricultural yield.

|

Outcome Variable: Agricultural (or Crop) Yield |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

Type of Farm Credit |

||||

|

Total Farm credit |

Small Scale Farm credit |

Medium Scale Farm credit |

Large Scale Farm credit |

|

|

Panel A: Agricultural Yield |

||||

|

Farm Credit (in log) |

0.291a |

0.297a |

0.309a |

0.209a |

|

(0.017) |

(0.017) |

(0.016) |

(0.015) |

|

|

HDI |

-1.750a |

-1.596a |

-0.696a |

-0.767a |

|

(0.252) |

(0.252) |

(0.253) |

(0.258) |

|

|

Population Density |

-0.001a |

-0.001a |

-0001a |

-0.001a |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

|

Rural Population |

-0.011c |

-0.009c |

-0.009c |

-0.011c |

|

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

|

|

Observations |

17,080 |

17,080 |

17,080 |

17,080 |

|

R2 |

0.329 |

0.329 |

0.332 |

0.325 |

|

Year Fixed Effects |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Crop-Type Fixed Effects |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Province Fixed Effects |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Panel B: Food Crops’ Yield |

||||

|

Farm Credit (in log) |

0.250a |

0.258a |

0.261a |

0.188a |

|

(0.026) |

(0.027) |

(0.024) |

(0.022) |

|

|

Observations |

7,044 |

7,044 |

7,044 |

7,044 |

|

Panel C: Cash Crops’ Yield |

||||

|

Farm Credit (in log) |

0.604a |

0.598a |

0.749a |

0.416a |

|

(0.045) |

(0.046) |

(0.042) |

(0.042) |

|

|

Observations |

3,802 |

3,802 |

3,802 |

3,802 |

|

Panel D: Pulses’ Yield |

||||

|

Farm Credit (in log) |

0.132a |

0.144a |

0.025 |

0.083a |

|

(0.033) |

(0.033) |

(0.030) |

(0.029) |

|

|

Observations |

4,050 |

4,050 |

4,050 |

4,050 |

|

Panel E: Seed Oil Yield |

||||

|

Farm Credit (in log) |

0.304a |

0.313a |

0.361a |

0.220a |

|

(0.042) |

(0.042) |

(0.039) |

(0.037) |

|

|

Observations |

2,184 |

2,184 |

2,184 |

2,184 |

Note: a, b and c denote the level of significance at the less than 1%, 5%, and 10% respectively. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. The unit of analysis is each individual crop i within district d during year t. The dataset comprises 16 different crops, spanning 114 districts of Pakistan, and covers an 11-year period from 2010 to 2020. Additional control variables incorporated crop-type (4 crop types)-, province (4 provinces)-, and year (11 years)- fixed effects to adjust for district-specific characteristics and temporal fluctuations during the study duration (2010-2020). For regressions in Panels B to E, all control variables, except the crop-type fixed effects, are employed. Source: authors ‘own calculation based on data on various sources given in data section.

of interest in a single regression model, we conducted separate regression analyses. In each analysis, we designated one of the following as the independent variable of interest: ‘total farm credit,’ ‘small scale farm credit,’ ‘medium scale farm credit,’ and ‘large scale farm credit.’ The findings, detailed in Table 3, unveil several significant patterns.

Correlation between farm credit and agricultural yield

Our study first examines the connection between farm credit and agricultural yield using a log-log regression model. The results indicate a positive and statistically significant correlation between farm credit and agricultural yield. Specifically, a 1 percent increase in farm credits from commercial banks within a district is associated with an average increase of 0.29 percent in agricultural yield for that district (see Column 1, Panel A). This finding is consistent with previous research conducted by (Bashir et al., 2009; Udoka et al. 2016; Chandio et al., 2017; Bekun et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2021; Yadav and Rao, 2024), which also reported a similar positive and significant relationship between agricultural credit and agricultural yield.

The allocation of farm credit in Pakistan adheres to a predetermined policy set by the State Bank of Pakistan, distributed among various farming scales based on their landholding sizes (see Table 1). Our analysis further reveals that an escalation in farm credit is directly correlated with increased agricultural yields at the district level across all categories of farm credit, whether small-scale, medium-scale, or large-scale. This relationship is particularly pronounced for small and medium-scale farm credits, where the magnitude of the correlation surpasses that of large-scale farm credit (refer to Columns 2-4, Panel A). This implies that credit from commercial banks significantly contributes to crop production for smaller and medium-sized farms, thereby improving their livelihoods.

Supporting prior studies (Hussain and Thapa, 2012; Chandio et al., 2017; Saqib et al., 2018) that emphasized the accessibility of farm credit for small farm holders with land between 2.5 to 5.00 acres, our study underscores the importance of promoting access to credit for small farmers. To address agricultural needs of small farmers, accessibility of farm credit to small farm holders is required to be increased (Ozdemir, 2024). This encouragement can lead to increased agricultural productivity and potentially improve their living standards. Historically, the size of a farmer’s landholding has been a significant obstacle in their ability to obtain formal credit from financial institutions (Shete and Garcia, 2011; Anang and Dagunga, 2023; Chaiya et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the State Bank of Pakistan steps in and sets a goal for commercial banks to provide 70% of farm credit to small landholders (see Table 1). This acknowledges their crucial contribution to subsistence farming and their potential for generating surplus production. Increasing small credit access could reduce reliance on costlier informal loans, benefiting struggling farmers.

Correlation between farm credit and yield of food crops

Given the critical role of food security in a world with a rapidly growing population, our research delves into the relationship between farm credit and the yield of food crops (see Panel B, Table 3). The findings suggest that an increase in total farm credit at the district level corresponds to higher food crop yields (see column 1, Panel B). Notably, this impact is more pronounced for both small scale and medium-scale farm credit compared to large-scale credit (see columns 2-4, Panel B). In practical terms, a 10 percent increase in each type of farm credit in a district leads to a respective 2.58 percent, 2.61 percent and 1.88 percent rise in food crop yields for small, medium and large-scale farmland, holding other factors constant. These results align with prior research (Asghar and Salman, 2018) highlighting the role of agricultural credit in ensuring food security.

Based on these findings, our study supports the current policy of the State Bank of Pakistan, which allocates farm credit to farmers based on their land ownership. Notably, directing around 90 percent of farm credit towards small and medium farmland proves more beneficial for farmers reliant on food crops for their livelihoods. This approach contributes to improving living standards in rural areas and can aid policymakers in designing poverty alleviation initiatives for these communities. Enhancing rural prosperity can also mitigate urban migration pressures, easing demands on urban infrastructure and investments, while simultaneously promoting the well-being and development of rural and suburban populations.

Correlation between farm credit and yield of cash crops

In our investigation, we have delved further into the dynamics of farm credit and its correlation with cash crop yields, revealing distinct patterns based on farm size (see Panel C, Table 3). Our analysis revealed a significant correlation between farm credit—whether allocated to small, medium, or large-scale farms—and the yields of cash crops, demonstrating a notably stronger effect for small and medium-scale farm credit relative to that observed for large-scale farm credit. Notably, the influence of farm credit exhibited significant variations across different farmland sizes, with the most substantial impact detected in medium-sized farmlands. Specifically, augmenting farm credit by 10 percent within a district resulted in a 5.98 percent surge in cash crop yield for small farmlands, a substantial 7.49 percent escalation for medium farmlands, and a 4.16 percent rise for large farmlands (see Columns 2-4, Panel C). These outcomes align harmoniously with prior research, including studies by Asaleye et al. (2020) and Bashir et al. (2007), which highlighted analogous positive effects of agricultural credit on cotton and sugarcane production, respectively. It is imperative to underscore the pivotal role of cash crops in national development, contributing significantly to food availability, economic growth, employment opportunities, and balance of payments.

Correlation between farm credit and yield of pulses

Our study further investigates the relationship between farm credit and pulses yield (see Panel D, Table 3). The findings indicate a positive link between small and large-scale farm credit and pulses production, but a no significant correlation with medium-scale credit at the district level (see Columns 2-4, Panel D). Increasing farm credit by 10 percent for small and large farms boosts pulses yield by around 1.14 and 0.83 percent. This suggests that providing small-scale farm credit could benefit poor farmers, aiding pulse cultivation, reducing poverty, and addressing dietary needs. Pulses, important sources of protein, play an important role in global nutrition and poverty alleviation providing benefits for poverty reduction, nutrition, and biodiversity maintenance (Majumdar, 2011; Ullah et al., 2020).

Correlation between farm credit and yield of edible oilseeds

Finally, our study investigates the connection between farm credit and the yield of edible oilseeds (see Panel E, Table 3). The findings reveal a noteworthy positive relationship between farm credit accessible to farmers in a district and the yield of oilseeds in that same district (see Column 1, Panel E, Table 3). This connection holds true for all three types of farm credit. Notably, the impact of small and medium-scale credit on oilseed yield is both statistically and economically significant. A 10 percent average increase in small and medium-scale farm credit from commercial banks to farmers in a district correlates with a respective 3.13 and 3.61 percent rise in oilseed yield, assuming other factors remain constant (see Columns 2 and 3, panel E). The positive correlation observed in large-scale farms is comparatively weaker in magnitude when contrasted with the credit extended to small and medium-scale farms (see Column 4, panel E).

Oilseeds play a crucial role in agricultural production, being used for edible oil and various daily purposes. Pakistan spends a substantial amount of foreign exchange annually on importing oilseed crushing and edible oils. In the period from July to March 2022, the country imported oilseeds worth Rs. 662.657 billion, equivalent to US$ 3.681 billion (Government of Pakistan, 2022). Consequently, boosting domestic oilseed cultivation through increased farm credit is vital for reducing foreign exchange outflow and addressing the current foreign exchange crisis in the country.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This study has shed light on the critical role of farm credit in enhancing agricultural yield in Pakistan—a country heavily dependent on its agricultural sector. The significance of these findings lies in the use of district-level data which provides a granular understanding of the impact of different types of farm credit on specific crop categories. This depth of analysis can inform policy makers and financial institutions in devising more effective credit distribution strategies and promoting agricultural development. The findings of this study should be considered with a caveat: these results reflect district-level variations rather than individual farm-level impacts. Also, the relationships observed are conditional correlations rather than purely causal.

Recommendations

Our findings show a strong and positive correlation between small and medium farm credit and crop yields across food crops, cash crops, pulses, and oilseeds. Therefore, a substantial portion of farm credit should prioritize small and medium farm owners.

The existing agriculture credit policy of the State Bank of Pakistan—allocating about 90 percent of credit to small and medium farms—is seemingly aligned well with the findings of this study. Therefore, we suggest that the current allocation strategy should be maintained due to its significant benefits to farmers who are reliant on food crops for their livelihoods. However, a rigorous and continuous monitoring and evaluation mechanism is essential for ensuring to allocate and utilize the fund effectively.

Based on findings of this study—that there exists a strong correlation between medium-sized farm credit and cash crop yield—therefore we recommend that policies should prioritize medium-sized farms for enhancing cash crop production. Given the economic importance of oilseed crop production and its role in reducing foreign exchange outflow for the country’s economy, we recommend to prioritize farm credit allocation to small and medium-scale farms for oilseed cultivation. This strategy can not only boost domestic oilseed production, but also decrease reliance on its imports, and eventually help to stabilize the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Pakistan can achieve sustainable growth in the agricultural sector, increase farmers’ livelihoods, and reap broader economic benefits when agricultural credit policies are tailored to farm owners according to their use in crop production. Thus, this study contributes as a valuable resource for policy makers and financial institutions committed to the long-term sustainable development of the agricultural sector in Pakistan.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to several individuals who provided invaluable support throughout various stages of our data collection. Special thanks to Maaz Ullah (Crop Reporting Service Officer, Government of Balochistan), Dr. Abdul Qayyum and Muddasir Jamil (Agriculture Department, Government of Punjab), Muhammad Kaleem (Crop Reporting Service Officer, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), Aftab Memon and Sarfaraz Bhutto (Crop Reporting Service Officers, Government of Sindh), Dr. Muhammad Ali Talpur (Ministry of National Food Security and Research, Islamabad), and Muhammad Anwaar Alam Khokhar (Agricultural Credit and Micro-finance Department, State Bank of Pakistan).

Author’s Contributions

Rehmat Ullah: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing.

Riaz Ahmed: Conceptualization, formal analysis, software, supervision, writing - original draft.

Muhammad Tahir: Methodology, supervision, writing - review and editing.

Abdul Majid Nasir and Mushtaq Muhammad: Writing - original draft, writing - review and editing.

Novelty Statement

The novel contribution of this study lies in its comprehensive analysis on the dynamic association of farm credit with crop yield at the district level in Pakistan. The results highlighting a strong positive correlation between small-scale farm credits and crop yield emphasize the need for adequate credit allocation to promote sustainable agricultural financing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest

References

Agbodji, A.E. and A.A. Johnson. 2019. Agricultural credit and its impact on the productivity of certain cereals in Togo. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade., 57(12): 3320-3336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1602038

Ahmed, R. and U. Mustafa. 2016. Impact of CPEC projects on agriculture sector of Pakistan: Infrastructure and agricultural output linkages. Pak. Dev. Rev., 511-527. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44986502

Anang, B.T. and G. Dagunga. 2023. Farm household access to agricultural credit in Sagnarigu Municipal of Northern Ghana: Application of Cragg’s Double Hurdle Model. J. Asian Afr. Stud., https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096231154234

Asaleye, A.J., P.O. Alege, A.I. Lawal, O. Popoola. and A.A. Ogundipe. 2020. Cash crops financing, agricultural performance and sustainability: Evidence from Nigeria. African J. Econ. Manag. Stud., 11(3): 481-503. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-03-2019-0110

Asghar, N. and A. Salman. 2018. Impact of agriculture credit on food production and food security in Pakistan. Pakistan J. Commer. Soc. Sci., 12(3): 851-864. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/193450

Bashir, M.K., Z.A. Gill and S. Hassan. 2009. Impact of credit disbursed by commercial banks on the productivity of wheat in Faisalabad district. China Agric. Econ. Rev., 1(3): 275-282. https://doi.org/10.1108/17561370910958855

Bashir, M.K., Z.A. Gill, S. Hassan, S.A. Adil and K. Bakhsh. 2007. Impact of credit disbursed by commercial banks on the productivity of sugarcane in Faisalabad district. Pak. J. Agric. Sci., 44(2): 361-363. https://www.pakjas.com.pk/papers/341.pdf

Bekun, F.V., A. Hassan and O.A. Osundina. 2018. The role of agricultural credit in agricultural sustainability: Dynamic causality. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol., 14(4): 400-417. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2018.098026

Bulman, A., K.Y. Cordes, L. Mehranvar, E. Merrill and Y. Fiedler. 2021. Guide on incentives for responsible investment in agriculture and food systems. Rome, FAO and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb3933en

Carter, M.R., 1989. The impact of credit on peasant productivity and differentiation in Nicaragua. J. Dev. Econ., 31(1): 13-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(89)90029-1

Chandio, A.A. and Y. Jiang. 2018. Determinants of credit constraints: Evidence from Sindh, Pakistan. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade., 54(15): 3401-3410. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1481743

Chandio, A.A., Y. Jiang, F. Wei, A. Rehman and D. Liu. 2017. Famers’ access to credit: Does collateral matter or cash flow matter? —Evidence from Sindh, Pakistan. Cogent Econ. Finance., 5(1): 1369383. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2017.1369383

Chandio, A.A., J. Yuansheng and M.A. Koondher. 2015. Raising maize productivity through agricultural credit: A case study of commercial banks in Pakistan. Eur. J. Bus. Manag., 7(32): 159-165. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/view/27034/27717

Chisasa, J. and D. Makina. 2013. Bank credit and agricultural output in South Africa: A Cobb-Douglas empirical analysis. Int. J. Bus. Economics Res., 12(4): 387-398. https://doi.org/10.19030/iber.v12i4.7738

Chaiya, C., S. Sikandar, P. Pinthong, S.E. Saqib and N. Ali. 2023. The impact of formal agricultural credit on farm productivity and its utilization in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability, 15(2): 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021217Government of Pakistan. 2000. Pakistan Economic Survey-1999-2000: Agriculture. Ministry of Finance-Islamabad, Pakistan.

Government of Pakistan. 2021. Pakistan Economic Survey-2020-2021: Agriculture. Ministry of Finance-Islamabad, Pakistan.

Government of Pakistan. 2022. Pakistan Economic Survey-2021-2022: Agriculture. Ministry of Finance-Islamabad, Pakistan.

Hussain, A. and G.B. Thapa. 2012. Smallholders’ access to agricultural credit in Pakistan. Food Secur., 4(1): 73-85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-012-0167-2

Johnston, B.F. and J.W. Mellor. 1961. The role of agriculture in economic development. Am. Econ. Rev., 51(4): 566-593. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1812786

Majumdar, D.K. 2011. Pulse crop production: Principles and technologies. PHI Learning Private Limited, New Delhi, India.

Ozdemir, D. 2024. Reconsidering agricultural credits and agricultural production nexus from a global perspective. Food Energy Secur., 13(1): e504. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.504

Peng, Y., R. Latief and Y. Zhou. 2021. The relationship between agricultural credit, regional agricultural growth, and economic development: The role of rural commercial banks in Jiangsu, China. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade., 57(7): 1878-1889. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2020.1829408

Poudel, M.P., S. Chen and W. Huang. 2014. Climate influence on rice, maize and wheat yields and yield variability in Nepal. J. Agric. Sci. Techno., B 4: 38-48. https://www.davidpublisher.com/Public/uploads/Contribute/552f79d47b890.pdf

Raza, A., G. Tong, F. Sikandar, V. Erokhin and Z. Tong. 2023. Financial literacy and credit accessibility of rice farmers in Pakistan: Analysis for Central Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa regions. Sustainability, 15(4): 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042963

Raza, J. and W. Siddiqui. 2014. Determinants of agricultural output in Pakistan: A Johansen Co-integration Approach. Acad. Res. Int., 5(4): 30-46. http://www.savap.org.pk/journals/ARInt./Vol.5(4)/2014(5.4-04).pdf

Rockström, J., J. Williams, G. Daily, A. Noble, N. Matthews, L. Gordon, H. Wetterstrand, F. DeClerck, M. Shah and P. Steduto. 2017. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio., 46: 4-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0793-6

Saqib, E.S., J.K.M. Kuwornu, S. Panezia and U. Ali. 2018. Factors determining subsistence farmers’ access to agricultural credit in flood-prone areas of Pakistan. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci., 39(2): 262-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.06.001

State Bank of Pakistan. 2022. Indicative credit limits and eligible items for agriculture financing 2022-23. State Bank of Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan. https://www.sbp.org.pk/acd/2022/C1-Annex.pdf (accessed 25 June, 2023).

Schultz, T.W. 1980. Nobel lecture: The economics of being poor. J. Political Econ., 88(4): 639-651. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1837306

Sertoglu, K., S. Ugural and F.V. Bekun. 2017. The contribution of agricultural sector on economic growth of Nigeria. Int. J. Econ. Financial Issues., 7(1): 547-552. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/article/view/3941

Shete, M. and R.J. Garcia. 2011. Agricultural credit market participation in Finoteselam town, Ethiopia. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ., 1(1): 55-74. https://doi.org/10.1108/20440831111131514

The Institute of Bankers Pakistan. 2022. Changing patterns in production and prices. J. Institute Banker Pak., 89(2): 24-30. https://ibp.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/IBP-Journal-April-June-2022-.pdf

Tiffin, R. and X. Irz. 2006. Is agriculture the engine of growth? Agric. Econ., 35(1): 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2006.00141.x

Udoka, C.O., D. Mbat and S. B. Duke. 2016. The effect of commercial banks’ credit on agricultural production in Nigeria. J. Financ. Account., 4(1): 1-10. https://www.sciepub.com/JFA/abstract/6607

Ullah, A., T.M. Shah and M. Farooq. 2020. Pulses production in Pakistan: Status, constraints and opportunities. Int. J. Plant Prod., 14(4): 549-569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42106-020-00108-2

UNDP. 2017. National human development report 2017: Pakistan. https://hdr.undp.org/content/national-human-development-report-2017-pakistan (accessed 19 August, 2023).

Webb, P. and E. Kennedy. 2014. Impacts of agriculture on nutrition: Nature of the evidence and research gaps. Food Nutr. Bull., 35(1): 126-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651403500113

Wineman, A., C.L. Anderson, T.W. Reynolds. and P. Biscaye. 2019. Methods of crop yield measurement on multi-cropped plots: Examples from Tanzania. Food Secur. 11(6): 1257-1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00980-5

World Food Programme. 2024. Ending hunger. https://www.wfp.org/ending-hunger. (accessed 7 July, 2024).

Yadav, I.S. and M.S. Rao. 2024. Agricultural credit and productivity of crops in India: Field evidence from small and marginal farmers across social groups. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ., 14(3): 435-454. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-05-2022-0092

Zulfiqar, F., J. Shang, M. Zada, Q. Alam and T. Rauf. 2021. Identifying the determinants of access to agricultural credit in Southern Punjab of Pakistan. GeoJournal., 86(6): 2767-2776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10227-y

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?