Mitigating Household Food Wastage: Does Awareness of Monetary Damage Matter?

Research Article

Mitigating Household Food Wastage: Does Awareness of Monetary Damage Matter?

Abid Jan* and Asad Ullah

Department of Rural Sociology, the University of Agriculture, Peshawar (KP), Pakistan.

Abstract | The current study aimed to analyze the association of household food wastage with awareness of monetary damage due to food wastage. The data was collected from 379 randomly selected respondents (18 years and onward age group) in eight union councils of four towns of District Peshawar. Chi–square and Kendall’s Tau-b tests were used to ascertaining the association between variables (awareness of monetary damage due to food waste, and food wastage at the household level). The study revealed that food wastage had a highly significant and negative association with having alternatives to expensive food items (P=0.000 and tau-b=-0.256), expansive food is less wasted compared to less expensive (P=0.000 and tau-b=-0.276), economic loss due to food waste compelling to prioritize food waste reduction strategy (0.000 and tau-b=-0.268), encouraging households to perceive their food waste habits through the lens of financial loss (P= 0.000 and tau-b=-0.292), the decision to prepare a single meal with the intention of utilizing leftovers and economizing expenses (P=0.000 and tab-b=-0.222), and planning of monthly food budget based on food preferences and prevailing market prices (P=0.000 and tau-b=-0.320). Furthermore, socioeconomic status explains the association between awareness of monetary damage and food wastage. People from high socioeconomic status, under the influence of awareness of monetary damage due to food wastage, were more likely to reduce food wastage than those from middle and low socioeconomic status groups. Effective awareness drive to control food wastage using appropriate communication channels, training and facilitation of families in planning meals, optimal food storage, regular kitchen inventory, and checking and creative cooking practices involving leftovers were some of the study recommendations.

Received | March 14, 2024; Accepted | August 01, 2024; Published | October 04, 2024

*Correspondence | Abid Jan, Department of Rural Sociology, the University of Agriculture, Peshawar (KP), Pakistan; Email: abidsociologist@gmail.com

Citation | Jan, A. and A. Ullah. 2024. Mitigating household food wastage: does awareness of monetary damage matter? Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 40(4): 1153-1163.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2024/40.4.1153.1163

Keywords | Food wastage, Monetary loss, Socioeconomic status, Awareness, Household, Peshawar

Copyright: 2024 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Enough food is produced at global level that is surplus from the needs of all human beings. Still, due to unsustainable practices and excessive consumption a major chunk of people remain hungry. Food loss and food waste are two important reasons of human hunger at global level (FAO, 2011). Generally, the terms food waste, food loss, and food wastage are used interchangeably; however, the terms are different on technical grounds. Food wastage occurs when edible food remains unconsumed or is discarded while it is still suitable for consumption (Buzby et al., 2014). Thus, food waste is a decrease in both the quality and quantity of food resulting from decisions and actions taken by consumers, food service providers, and retailers. On the other hand, food loss pertains to the production and harvesting of edible plant and animal components intended for human consumption but not actually consumed (FAO, 2011; Yildirim et al., 2016).

It is estimated that approximately 1.3 billion tons of food intended for human consumption are wasted or lost each year across the food supply chain, posing a significant threat to food security, both economically and environmentally (Ganglbauer et al., 2013). The estimated financial value of food waste and loss amounts to $936 bn USD, an amount sufficient to prevent 1/8th hungriest population of the world and to satisfy the global challenge demand for food which is expected to reach 150 % to 170 % of the current demand by 2050. The socio-environmental losses created due to such wastage and losses add to human miseries (FAO, 2011). According to UN (WFP), the live hunger map estimated that worldwide 957 million people have not enough food to eat on regular basis as the requirement of human body on daily basis and that included 93 deprived countries in all and it is also shocking that one billion people are living in extreme poverty condition out of eight billion people on the earth. So, one billion, as astonishing fact, are living in extreme poverty due to which people are deprived from basic essentials of life like education, shelter and safe drinking water etc. While more than a billion people live on less than $1.25 per day which is insufficient to pay for one gallon of milk at market price (UNEP, 2021).

In Pakistan, it is a startling fact that almost 36 million tons of food is wasted every year, equivalent to every resident of Karachi, Lahore, and Hyderabad throwing out their whole lunches and dinners every day. The food wastage includes loss of food at different stages of food production and supply chain process i.e., post-harvest handling, agriculture processing, distribution and consumption etc. throughout the year. Diverse weather conditions of Pakistan add to the food wastage. On the other side global hunger index rank Pakistan on 94th position. The average Pakistani household spends 50.8 percent of its monthly income on food and about 61 million people are food insecure and struggling to survive from hunger (FAO, 2011).

Awareness of monetary damage due to food wastage is an important reason to avoid food waste. It refers to an individual’s understanding and recognition of the economic costs associated with wasting food. Food wastage has multiple consequences which have direct and indirect bearings on household monetary value in addition to effects on food supply chain. When people become aware of the financial implications of throwing away food, it can significantly influence their food waste behavior (Graham-Rowe et al., 2014; Quested et al., 2013). In addition, such economic motivation crated due to awareness of monitory damage due to food waste prompt behavioral changes in shopping and meal planning. Such consumers purchase items with long shelf life, properly refrigerate the products and consume it before it spoils (Quested et al., 2013). Such awareness of monitory losses in consumers not only reduce overbuying of food items but can also make individuals to appreciate the resources that go into food production, including water, energy, and land. This appreciation strengthens sense of collective environmental responsibility to minimize food waste. Thus, highlighting financial benefits of food conservation and tracking of food wastage is recommended as important starting point for food wastage control related awareness programs (Parizeau et al., 2015).

Food wastage has multiple consequences which directly and indirectly impacts the household monetary value along with food supply chain organizations. Those consumers who have knowledge of economic costs of food wastage are generally willing to change their behavior to prevent food wastage as saving money is the driving factor to motivate the individuals to avoid food waste. When individuals recognize the economic implications of wasting food, they are more motivated to adopt practices that minimize food wastage, leading to cost savings for households and societies (Graham-Rowe et al., 2014; Quested et al., 2013). Furthermore, as the income level of the consumer increases food wastage also become high. High income and low food cost compared to others expenses leads to over purchase of food and its subsequent mismanagement and wastage (Pearson et al., 2013). According to FAO the incautious behavior of consumers produces more food wastage because they have enough resources (Gustavsson et al., 2011).

This research study is designed to assess the association of food wastage at household level with awareness of monitory damage due to food loss. Furthermore, it is assessed that how socioeconomic status influence as a control variable affect the above association.

Materials and Methods

The current research study was conducted in district Peshawar of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The district Peshawar is administratively divided into four town (Town-I, Town-II, Town-III, Town-IV) and 357 Neighborhood/village councils, out of which 227 councils are rural and 130 are urban.

Under the multistage stratified random sampling technique all the four towns (Town-1, Tow-II, Town-III, Town-IV), of the district Peshawar were included in the sampling process. At the next stage one urban and rural council (town/village councils) were randomly selected from each town. In this way eight town/village councils namely, Gulbahar, Akhoon Abad (Town-1), Hassan Gari and Shahi Bala (Town-II), University town and Regi, (Town-III), Hazar Khwani and Badabera Maryumzai, (Town-IV) were randomly selected (Table 1). The total household population of eight selected towns/ village council stands at 38080 households. For calculation of sample size, the procedure recommended by Chaudhry and Kamal (2009) was adopted, thus the required sample size for the population of 38080 household was worked as 379. The required sample is proportionally allocated to each neighborhood/village council by using proportional allocation procedure recommended by (Bowley, 1926).

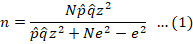

The formula for sample size determination is given below:

N= Total number of households =38080, P=population proportion = 0.50, q=opposite proportion q= (1-p) = 0.50, z = confidence level = 1.96, e = margin of error = 0.045

Bowley (1926) presented formula for proportional allocation of sample size is as under.

Where; nh = sample size required for each irrigation outlets, N= total population of farmers at each irrigation outlets. N= total population of the farmer, n = required sample size (Table 1).

Respondents characteristics, selection and interview

Household is the sampling unit for the current study. A household is defined as “an individual or group of individuals living in a house and sharing meals”. In Pakistani setup a household may comprise of a single or multiple families that share a common kitchen and meals. From the population frame (number of households in all selected neighborhood or village councils) the required sample of household was selected through lottery method of simple random sampling. Furthermore, a representative of selected household who is well versant with the study variables under investigation and willing to respond to the questions in an amicable way was interviewed for data collection on their home. Thus, the study respondents were the persons from randomly selected households who are older than 18 years of age and know the daily food preparation, storage, and wastage inside their homes.

The conceptual framework comprise on two independent variable (awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and socioeconomic status of the respondents) and one dependent variable food wastage (Table 2).

Measurement of variables

Awareness of monitory damage due to food waste variable was measured on (8 items), where positive response on five or more items was considered as high awareness of monitory damage due to food waste (coded as 1) and positive response on less than five items was considered as low awareness of monitory damage due to food waste (coded as 0).

The modified socioeconomic status scale by Oakes and Rossi (2003) was used for measurement of family socioeconomic status of the respondents. The composite score, based on quantitative approach, is grouped into three categories. Thus, a respondent whose composite score on the socioeconomic scale range from three to seven was ranked into low socioeconomic status family group and coded as 0. In Table 2, the respondents score range between eight to eleven on the scale was ranked into middle socioeconomic status group (coded as 1) and those who’s scored within the range of 12 to 15 on the scale were ranked in high socioeconomic status family group and coded as 2.

The overall food wastage at household level was measured by summing up four component of weekly food wastage i.e., amount of completely unused food that is wasted/discarded (food, vegetable, meats, packages, complete bread), partly used food that is wasted/discarded, (bread slices, half packages, cut fruit/vegetables, milk), meal leftover that are wasted/discarded (meal left on plate) and leftover spoiled and discarded after storage, (food left in fridge for later use). Moreover, Herpan et al. (2019) scale is used to measure main reasons of food wastage (14 item scale), activities to control food wastage (9 item scale) and disposal of food waste (5 item scale). Respondents having positive response on seven or more items of main reasons of food wastage scale were ranked as lack of planning regarding consumer food consumption (coded as 0) while the rest were categorized as satisfactory planning to avoid food wastage (coded as 1). Moreover, positive response on five or more items on activities to control food wastage scale, the respondents were grouped into the category proper planning the activities to avoid food wastage (coded as 1), while the rest were grouped into lack of planning of the activities to control food wastage (coded as 0). Likewise, respondents having positive response on four or more item of disposal of food wastage scale were ranked as having satisfactory knowledge of proper disposal of food wastage (coded as 1) while the rest were grouped as unsatisfactory knowledge of proper disposal of food waste (coded as 0).

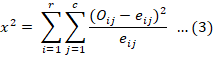

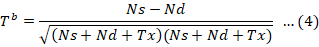

For the analysis of data, the chi-square test and Kendall’s Tau-b test were used at bi-Variate and multi-Variate level to measure the association and direction of the independent and dependent variables. At bi-Variate level the association between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and food wastage was determined, and multi-variate level socioeconomic status of the respondents was introduced as control variable to find the spuriousness of association between said variables. The mathematical form of chi-square test (Tai, 1978, Equation 3) and Kendall’s Tau-b test (Nachmias and Chava, 1992, Equation 4) are given below:

χ2 =Chi Square, Oij = Observed frequencies in ith row and jth column, eij = Expected frequencies regarding ith row and jth column, r = number of rows, c = number of columns, Df = (r-1) (c-1).

Kendal Tau-b is calculated by using the following Equation 4, (Nachmias and Chava, 1992).

Where; Tb = Kendall’s Tau-b, Ns = same order pairs, Nd = different order pairs, Tx = pairs tied on X

Results and Discussion

Awareness of monetary damage due to food waste

Awareness of the monetary damage due to food waste is crucial in understanding the economic impact of this issue. Food waste not only leads to the loss of valuable resources and labor invested in producing, processing, and transporting food, but it also has significant financial implications for households, businesses, and the economy as a whole. Money spent on purchasing food that goes to waste could have been used for other essential needs. By raising awareness about the monetary damage caused by food waste, individuals, businesses, and policymakers can work together to implement strategies that reduce food waste, promote sustainable food management, and maximize the economic benefits of the food supply chain.

Results on awareness of monetary value of the household due to food waste are given in Table 3 showing that 67.3 percent respondents endeavored to waste less because they spent a large amount of their income on food, 78.6 percent agreed that food waste was the loss of money, 71.5 percent purchased less expensive alternates for expensive food, and 68.1 percent agreed that expensive food was least wasted than less expensive food. Households often spend a significant portion of their income on food. Therefore, the households made efforts to make it essential to minimize food waste to save money, stretch their budget, and improve their overall financial well-being. Type of food wasted also varied on the basis of its economic worth. Expensive food was seldom wasted compared to low price food items. However, the households always searched for less expensive food items to lower their food cost. The results mention above validates the finding of Quested et al. (2013) who described that food expanses rank among top few household expenses. Member’s in charge of food purchase try to find best food items in low price on one side and motivate members for full utilization of food and avoid food waste to streamline family budget. Making use of all purchased ingredients and leftovers means getting the full value out of each item and stretching, the budget further. This can be especially important for families with limited financial resources (Halloran, 2014). Such families often opt for less expensive alternatives for expensive food items as a cost-saving measure (Drewnowski and Eichelsdoerfer, 2010). This approach allows for diverse and satisfying meals without breaking the budget (Ortega et al., 2000). Expensive food items are often perceived as having higher value, leading to more careful handling and consumption. People tend to be more conscious of wasting something they consider valuable (Lapinski et al., 2013).

Similarly, 81.0 percent of respondents were compelled to prioritize food waste reduction strategy due to economic loss, 84.7 percent agreed to motivate their household to recognize them that food waste is a loss of money, moreover, 72.0 percent of respondents have planned to cook one-time meal to use leftovers and save money, and 79.7 percent planned their monthly food budget according to food choices and market prices to limit food waste and expenses. Minimizing food expenses and food wastage at the household level is not only financially beneficial but also contributes to reducing overall food waste and its environmental impact. Planning meals ahead of time, creating a shopping list based on the planned meals, and sticking to it helps prevent impulse purchases and ensures that only needful items are purchased, reducing the chances of food going to waste and enables effective use of leftovers. The finding of FAO (2013) reported that the monetary impact of food wastage is staggering as it is estimated

Table 1: Proportional allocation of required sample size to selected town.

|

District name |

Tehsil/ Town name |

Neighbor councils/ Village councils |

Total household |

Sample size |

|

Peshawar |

Town-I |

Gulbahar (NC) |

3840 |

38 |

|

Akhoonabad (VC) |

3249 |

32 |

||

|

Town-II |

Hassan Gari II (NC) |

6482 |

65 |

|

|

Shahi Bala (VC) |

3910 |

39 |

||

|

Town-III |

University Town (NC) |

8202 |

81 |

|

|

Regi (VC) |

4985 |

50 |

||

|

Town-IV |

Khazar khwani-I (NC) |

4391 |

44 |

|

|

Badabera Maryam Zai (VC) |

3021 |

30 |

||

|

Total |

38080 |

379 |

Source: Bureau of Statistics Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Table 2: Conceptual framework of the study.

|

Control variable |

Independent variable |

Dependent variable |

|

Socioeconomic status of the respondents |

Awareness of monetary damage due to food waste |

Food wastage |

Table 3: Frequency distribution and proportion of the respondents on the basis of awareness of monetary damage due to food waste.

|

Statements |

Yes |

No |

Total |

|

I spend a remarkable amount of my income on food, so I always endeavor to waste less |

289 (67.3) |

90 (23.7) |

379 (100) |

|

I look at the food waste as the loss of money |

298 (78.6) |

81 (21.4) |

379(100) |

|

Our family members purchase less expensive alternates for expensive food |

271 (71.5) |

108 (28.5) |

379(100) |

|

Expensive food is least wasted than less expensive food |

258(68.1) |

121 (31.9) |

379 (100) |

|

Economic loss due to food waste is compelling to me to prioritizes food waste reduction strategy |

307 (81.0) |

72 (19.0) |

379 (100) |

|

You motivate household to see their behavior regarding food waste as money waste |

321 (84.7) |

58 (15.3) |

379 (100) |

|

You have planned to cook one time meal to use leftovers and save money |

273 (72.0) |

106 (28.0) |

379 (100) |

|

You plan your monthly food budget according to food choices and market prices to limit your food waste and expenses |

302 (79.7) |

77 (20.3) |

379 (100) |

Frequencies are given in parenthesis.

Table 4: Association between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and food wastage.

|

Independent variable (monetary damage due to food waste and food waste |

Dependent variable |

Statistics-χ2, (P-value and tau-b) |

|

I spend a remarkable amount of my income on food, so I always endeavor to waste less |

Food wastage |

χ2=11.231(0.001) tau-b=-0.172 |

|

I look at the food waste as the loss of money |

Food wastage |

χ2= 40.498(0.000) tau-b=-0.327 |

|

Our family members purchase less expensive alternates for expensive food |

Food wastage |

χ2=24.746(0.000) tau-b= -0.256 |

|

Expansive food is least wasted than less expensive food |

Food wastage |

χ2= 28.771 (0.000) tau-b= -0.276 |

|

economic loss due to food waste is compelling to me to prioritize food waste reduction strategy |

Food wastage |

χ2= 27.174 (0.000) tau-b=- 0.268 |

|

You motivate households to see their behavior regarding food waste as money waste |

Food wastage |

χ2= 32.322 (0.000) tau-b= -0.292 |

|

You have planned to cook one time meal to use leftovers and save money |

Food wastage |

χ2= 18.635 (0.000) tau-b = -0.222 |

|

You plane your monthly food budget according to food choices and market prices to limit your food waste and expenses |

Food wastage |

χ2= 38.809 (0.000) tau-b = -0.320 |

that one-third of the world’s food production is lost or wasted annually. In economic terms, this amounts to approximately $1 trillion worth of food being lost or wasted globally each year. Beyond the direct financial losses, food wastage also has broader economic implications. For instance, reducing food wastage is not only crucial to minimizing the financial losses at different stages of the supply chain but also to achieving sustainable food systems that can support the world’s growing population while minimizing environmental impacts. Efforts to reduce food wastage involve implementing better agricultural practices, improving storage and transportation infrastructure, addressing consumer behavior through education and awareness campaigns, and collaborating among stakeholders in the food industry to find innovative solutions (FAO (2013)). Households can be motivated to minimize food wastage and save money by understanding the significant benefits and positive outcomes associated with these efforts. By being mindful of their food consumption and minimizing wastage, families can stretch their food budget and have more money available for other essential expenses or savings (Graham-Rowe et al., 2014). This behavior can lead to a ripple effect, inspiring others to adopt more sustainable practices in their own homes (Visschers et al., 2016). For instance, market research and comparing market prices of various food items help in budgeting more accurately and reduces purchase cost of food items. Similarly, cooking one time using leftovers is a cost-saving practice that can help households reduce food wastage and make the most of their food budget. Instead of letting leftovers go to waste, incorporating them into new meals can stretch the value of the initial investment in food purchases (USDA, 2021; EPA, 2022; Roe et al., 2019).

Association between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and food wastage

The awareness of monetary damage due to food waste is a significant factor that can influence individuals’ behaviors and attitudes towards food wastage. When individuals become conscious of the financial costs associated with throwing away food, they are more likely to adopt practices that reduce food waste. This awareness can have both direct and indirect effects on their food consumption and disposal habits. Understanding the monetary implications of food waste can directly impact individuals’ purchasing decisions and consumption patterns. When people realize that wasting food equates to wasting money, they are more inclined to buy only what they need, use leftovers effectively, and ensure proper storage to extend the shelf life of perishables. The indirect effects of awareness of financial losses due to food waste include development of a stronger sense of responsibility and accountability for minimizing waste. The association between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and food wastage are presented in Table 4 and discuss as follow.

The results in Table 4 show a significant (P=0.001) and negative (tau-b=-0.172) association between allocating a substantial portion of income to food expenses and striving to minimize food waste. Moreover, highly significant (P= 0.000) and negative (tau-b= -0.327) association was found between viewing food waste as a direct financial loss with food wastage. These results highlight the importance of economic factors in influencing individuals’ behaviors towards food consumption and waste. When people perceive food waste as a financial loss, they are more likely to take steps to minimize it. Thus economic incentives and consequences play a crucial role in shaping human behavior. Individuals who consider food waste as a direct financial loss may become more mindful of their food purchasing habits, portion control, and meal planning, all of which contribute to reduced food wastage. The concept of financial awareness and its impact on reducing food waste is supported by the broader literature on behavioral economics and psychology. Perceiving food waste as a financial loss can lead to more responsible behavior (Pahl et al., 2019). People who equate food waste with financial loss are more likely to engage in behaviors that minimize waste (Thøgersen, 2015). In today’s economic and environmental climate, people recognize that a substantial proportion of their income is dedicated to food; therefore, they are more motivated to maximize the economic and environmental value of their purchases by minimizing waste (Vlaeminck and Rousseau, 2018; Griskevicius et al., 2012; Stancu et al., 2016). High food expenses, due to budget constraints, limit individuals to adopt behaviors aimed at reducing food waste to stay within their budget (Wang and Sun, 2019; Zepeda and Li, 2017). Moreover, the practice of family members opting for more affordable alternatives to expensive food items was highly significant (P=0.000) and negatively associated (tau-b=-0.256) with food wastage. Similarly, a highly significant association (P=0.000) and negative association (tau-b=-0.276) was found between expansive food is less wasted compared to less expensive food and food wastage. In addition, economic loss due to food waste compelling to prioritize food waste reduction strategy was found highly significant (0.000) and negative (tau-b=-0.268) association with food wastage. Similarly, encouraging households to perceive their food waste habits through the lens of financial loss emerges as highly significant (0.000) and negative (tau-b=0.292) in association with food wastage. These results highlight the intricate interplay between economic considerations, value perceptions, and wasteful behaviors within households. When family members opt for less expensive options as substitutes for pricier food items, there is an increased likelihood of higher food wastage. The perception that those cheaper alternatives are often considered being of lower value, which lead to reduced sense of responsibility and care in their consumption. Consequently, individuals are more inclined to discard these items, contributing to food wastage. Less expensive food items might be seen as more disposable, leading to higher levels of wastage. In budget constraints, individuals and households may prioritize cost savings when selecting food products. This behavior is often driven by the desire to maximize the value obtained from the available resources. However, this cost-conscious approach inadvertently lead to a mindset where less expensive food items are perceived as having lower value or importance, affluent and readily available that potentially contributing to a higher likelihood of wastage (Rutten, 2018). Prioritizing affordability may lead to bulk buying to take advantage of discounts (Verain et al., 2015). While these behaviors can save money, they can also result in excess food that is more likely to go to waste (Evans and Abrahamse, 2015; Carfora et al., 2019). Lower-cost food items sometimes require more skill to transform into appealing meals. Families without strong food management skills may struggle to utilize these items effectively, leading to waste (Parizeau et al., 2015; Verneau et al., 2016). On the other hand, when families experience economic losses due to food waste, it serves as a tangible reminder of the financial impact of wasting food (Quested et al., 2013). This burden motivates them to take concrete steps to reduce waste. Economic loss prompts a change in behavior, encouraging individuals to adopt practices such as meal planning, proper storage, and portion control (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2015). Moreover, the decision to prepare a single meal with the intention of utilizing leftovers and economizing expenses exhibited a highly significant (P=0.000) and negative (tab-b=-0.222) association with food wastage. Similarly, plaining of monthly food budget based on food preferences and prevailing market prices, with the aim of both decreasing food waste and managing expenses, showed a highly significance (P=0.000) and a negative association (tau-b=-0.320) with food wastage. Proactive meal planning and cost-consciousness significantly contribute in reducing food waste. As the frequency of planning and cooking a one-time meal to use leftovers and cut down on costs increases, there is a corresponding increase in the reduction of food wastage. Stancu et al. (2016) found that individuals who engage in meal planning tend to waste less food, as they have a clearer idea of what ingredients they need and can better manage their portions. Moreover, planning a single meal with the intention of using leftovers contributes to a reduction in food wastage. Parizeau et al. (2015) added that households that make conscious efforts to use leftovers tend to discard less food. Such behaviors are associated with cost-saving motives, as individuals recognize the economic benefits of utilizing food effectively. This planning process often involves selecting ingredients that can be used in multiple dishes (Rutten et al., 2019). A thoughtful and strategic approach to food management by considering personal tastes and economic factors helps in saving expenses and play an active role in minimizing food wastage, aligning with sustainable consumption practices (Quested et al., 2013; Graham-Rowe et al., 2014). Planning meals and shopping with consideration for personal preferences and household needs can lead to a decrease in food wastage. Budget planning based on food preferences and market prices encourages individuals to efficient financial allocation and controlling food wastage (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2015). Awareness of monitory damage due to food waste is reflected in consciousness to see food waste as economic loss, purchase of inexpensive food, prioritizing waste reduction strategies and use of usable leftover. Thus recognition of economic losses due to food wastage are compelling to amend and adopt the behavioral traits that are less wasteful.

Association between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and food wastage controlling socio-economic status of the respondents)

Results in Table 5, show that the association of awareness of monetary damage due to food waste on food wastage in the context of the low socio-economic status of the respondents was significant (P=0.000) and negative (tau-b=-0.437). Moreover, the association of awareness of monetary damage due to food waste on food wastage in the context of the middle socioeconomic status of the respondents was highly significant (P=0.000) and negative (tau-b=-0.490). Furthermore, the association of awareness of monetary damage due to food waste on food wastage in the context of high socioeconomic status of the respondents was highly significant (P=0.000) and negative (tau-b=-0.546) association. The value of the level of significance and Tau-b for entire table showed highly significant and negative association (P=0.000 and tau-b=-0.508) between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste on food wastage. Thus, socioeconomic status explained association between awareness of monitory damage and food wastage. People from high socioeconomic status, under the influence of awareness of monitory damage due to food wastage, were more likely to reduce food wastage than those from middle and low socioeconomic status groups. These findings suggest that raising awareness about the economic consequences of food waste are particularly impactful in high socioeconomic status group, as well as in middle and low socioeconomic statuses. The result emphasizes the importance of educating individuals about the financial impact of food waste across different economic backgrounds, as it appears is an effective strategy for reducing wasteful food behaviors. High socioeconomic status people, due to their higher income and education status have better access to information and higher understanding of economic losses due to food wastage. Therefore, such awareness reduces their likelihood of food wastage due to better awareness. In low SES households, on the other hand, there is a heightened awareness due to exposure to food saving programs and face financial constraints due to limited resources, resulting in controlling food wastage (Carolan, 2018). People in these households are more likely to feel the economic impact of food wastage directly.

Table 5: Association between awareness of monetary damage due to food waste and food wastage controlling socio-economic status of the respondents).

|

Family type of the respondents |

Independent variable |

Dependent variable |

Statistics χ2, (P-value and tau-b) |

Statistics χ2, (P-value) and tau-b for entire table |

|

Low socioeconomic status |

Awareness of monetary damage due to food waste |

Food wastage |

χ2=11.650 (0.001) tau-b=-0.437 |

χ2=97.696(0.000) tau-b=-0.508 |

|

Middle socioeconomic status |

Awareness of monetary damage due to food waste |

Food wastage |

χ2=35.950 (0.000) tau-b=-0.490 |

|

|

High socioeconomic status |

Awareness of monetary damage due to food waste |

Food wastage |

χ2=50.058 (0.000) tau-b=-0.546 |

This awareness motivates them more to be mindful of their food consumption and reduces waste (Buzby and Hyman, 2012). Lower socioeconomic backgrounds have a scarcity mindset, where they are acutely aware of resource limitations. These mindsets are more careful planning and utilization of food resources to avoid waste (Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013). Similar economic status communities share information and strategies for making the most of their resources. These social aspects contribute to a strong awareness of food waste issues and the importance of minimizing wastage (Dachner and Tarasuk, 2002). Middle socioeconomic households have a reasonable level of financial stability, but they are still sensitive to economic concerns. They are aware that reducing food waste lead to cost savings, making them more inclined to minimize wastage. They are typically more engaged in consumer culture and have a higher standard of living. This lifestyle leads to a greater consciousness of the financial value of food, thereby motivating them to reduce waste (Teixeira et al., 2012). This social influence drives them to be more aware and proactive in minimizing waste. They have better access to information through education and media, which increase their awareness of food waste issues and solutions. Awareness alone is not enough to reduce food waste; it often requires corresponding behaviors. They have the resources and knowledge to implement strategies like meal planning and proper storage to reduce food waste (Carolan, 2018). High socioeconomic status groups have better awareness opportunities. This may lead to greater concern about food wastage costs compared to lower socioeconomic groups. Hence, in this scenario, they are more likely to waste less food with considerations to the monetary consequences. However, unawareness of monitory damage of food waste may lead high socioeconomic status groups to engage in a more consumer-oriented lifestyle, which include buying and discarding items more frequently, including food. Paradoxically, they are less aware of the environmental and financial impacts of their behaviors, including food waste and less motivated to reduce waste due to their relative affluence (Stuart, 2019).

Conclusions and Recommendations

Awareness of monitory loss due to food wastage at household level is of highest importance to make people understand the economic impact of discarded food, evoking behavioral responses like amending over shopping and excess meal preparation habits etc. Moreover, visualizing food losses in financial terms is catalyzed by the respondents low financial standings and high literacy level, and is compelling to revisit the behavioral aspects of food losses. Therefore, awareness of monetary damage due to food wastage has important policy implications in developing positive attitude among members at household level to control food wastage. Moreover, recognizing the role of socioeconomic status, further emphasizes the need for tailored interventions that consider the diverse contexts within which food-related decisions are made. Through a holistic and informed approach, society can move towards a future where food is valued, and wastage is minimized for the benefit of individuals and the planet.

The study made the following recommendations:

- Encourage families to plan their meals in advance, taking into consideration the ingredients on hand and their expiration dates. This helps in minimizing over-purchasing and ensures that all purchased items are used efficiently.

- Advocate for mindful shopping habits, including making shopping lists, buying in smaller quantities, and avoiding impulsive purchases. This reduces the likelihood of food items expiring before consumption.

- Educate individuals about optimal food storage practices, emphasizing the importance of refrigeration, proper use of pantry space, and appropriate packaging. Proper storage extends the shelf life of perishable items.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the households for providing the data. The authors are also thankful to the University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan, for providing a good platform for this research study.

Novelty Statement

This research study was conducted to determine the household behavior and awareness regarding food wastage at household level in district Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan. No such research was conducted before in the study area.

Author’s Contribution

Abid Jan: Conceived idea, designed research, collected data, analyzed data and prepared draft.

Asad Ullah: Supervised research, designed research, analyzed data and edited draft.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Aschemann-Witzel, J., I.E. de Hooge, P. Amani, T. Bech-Larsen and M. Oostindjer. 2015. Consumer food waste behavior research group. Consumer-related food waste: Causes.

Bowley, A.L., 1926. Measurements of precision attained in sampling. Bull. Int. Stat. Inst. Amsterdam, 22

Buzby, J.C. and J. Hyman. 2012. Total and per capita value of food loss in the United States. Food Policy, 37(5): 561-570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.06.002

Buzby, J.C., H.F. Wells and J. Hyman. 2014. The estimated amount, value, and calories of postharvest food losses at the retail and consumer levels in the United States. Econ. Inf. Bull. (EIB-121) pp. 58. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2501659

Carfora, V., D. Caso and P. Sparks. 2019. The role of food service and food retailing in the food waste challenge: A review. Food Res. Int., 125: 108567.

Carolan, M.S., 2018. Food, morals and meaning: The pleasure and anxiety of eating. Routledge.

Chaudhry, P. and R. Kamal. 2009. Protecting intellectual property rights: The special case of developing countries. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights, 14(5): 450-459.

Chaudhry, S.M., 2009. Introduction to statistical theory, 8th edition, Publisher: Lahore, Pakistan: Ilmi Kitab Khana.

Dachner, N. and V. Tarasuk. 2002. Homeless squeegee kids: Food insecurity and daily survival. Soc. Sci. Med., 54(7): 1039-1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00079-X

Drewnowski, A. and P. Eichelsdoerfer. 2010. Can low-income americans afford a healthy diet? Nutr. Today, 44(6): 246–249. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0b013e3181c29f79

EPA, 2022. Methane emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse

Evans, D. and W. Abrahamse. 2015. Valuing low carbon consumption: The constraining effect of psychological distance. Glob. Environ. Change, 34: 13-21.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2013. Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources. http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf

FAO, 2011. Global food losses and food waste: Extent, causes and prevention. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf.

Ganglbauer, E., G. Fitzpatrick and R. Comber. 2013. Negotiating food waste: Using a practice lens to inform design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. pp. 2959-2968.

Graham-Rowe, E., D.C. Jessop and P. Sparks. 2014. Identifying motivations and barriers to 789 minimizing household food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recyc., 84: 15-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.12.005

Griskevicius, V., J.M. Tybur, A.W. Delton and T.E. Robertson. 2012. The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: A life history theory approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol., 102(1): 69-82. https://doi.org/10.1037/e634112013-061

Gustavsson, J., C. Cederberg, U. Sonesson, R. van Otterdijk and A. Meybeck. 2011. Global food losses and food waste: Extent, causes, and prevention. FAO, Rome.

Halloran, A., J. Clement and C. Kornbrust. 2014. Food donations in retailing: Measuring and managing shrink in the grocery supply chain. J. Bus. Logist., 35(3): 256–269.

Herpan, C., E. Van Herpen, H.C.M. Trijp and S.J. Sijtsema. 2019. Understanding land management practices: A focus on motivations and constraints. Land Use Policy., 81: 103-112

Lipinski, B., C. Hanson, J. Lomax, L. Kitinoja, R. Waite and T. Searchinger. 2013. Reducing food lost and waste. Available at: https://pdf.wri.org/reducing_food_loss_and_waste.pdf

Mullainathan, S. and E. Shafir. 2013. Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Macmillan.

Nachmias, D. and N. Chava. 1992. Research method in the social sciences. 3rd ed. St. Martin’ spress. Inc., New York, USA.

Oakes, J. M. and P.H. Rossi. 2003. The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Sci. Med., 56(4): 769-784.

Ortega, R.M., A.M. López-Sobaler, M.E. Quintas, P. Andrés and A.M. Requejo. 2000. Short-term effects of a hypocaloric diet with low glycemic index and low glycemic load on body adiposity, metabolic variables, ghrelin, leptin, and pregnancy rate in overweight and obese infertile women: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 72(1): 151–161.

Pahl, S., P.R. Harris, H.R. Todd and D.R. Rutter. 2019. Comparing actual food waste behaviors to self-reported behaviors as a more valid measure of food waste: Exploring the potential for ecological momentary assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recyc., 141: 79-87.

Parizeau, K., M. von Massow and R. Martin. 2015. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Mangae., 35(2015): 207-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.019

Pearson, D., M. Minehan and R. Wakefield-Rann. 2013. Food waste in Australian households: Why does it occur? J. Food Prod. Market., 19(3): 235-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2013.724365

Quested, T.E., E. Marsh, D. Stunell and A.D. Parry. 2013. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recyc., 79: 43-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.04.011

Roe, B., B. Shankar, A. Evans and C. Fotopoulos. 2019. An exploration of household food waste across time scales. Ecol. Food Nutr., 58(3): 243–266.

Rutten, R., P.T.M. Ingenbleek and H.C.M. Trijp. 2019. The development and validation of a tool to measure consumers’ readiness to reduce food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl., 149: 371-384.

Rutten, M., 2018. The economic impacts of (reducing) food waste and losses: A graphical exposition. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253240278_WORKING_PAPER_ScSocial_Sciences.

Stancu, V., P. Haugaard, L. Lähteenmäki and K.G. Grunert. 2016. Determinants of consumer food waste behavior: Two routes to food waste. J. Cleaner Prod., 134: 140-146.114-129. https://doi.org/10.1037/t47710-000

Stuart, T. 2019. Waste: Uncovering the global food scandal. Penguin Books

Tai, H. 1978. Land reform and politics: A comparative analysis. University of California Press

Teixeira, R., A. Pires, A. Fernandes and P. Vicente. 2012. Portuguese consumer attitudes towards bread consumption. Br. Food J., 114(1): 114-127.

Thøgersen, J., 2015. From awareness to action: The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in promoting sustainable consumption. J. Soc. Issues, 71(2): 391-407.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2021. Food waste index report 2021. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2021. Food storage and preservation. Retrieved from https:// www.usda. gov/media/ blog/2017 /04/21/food-storage-and-preservation-how-keep-best-taste-and-nutrients

Verain, M.C., H. Dagevos and G. Antonides. 2015. Sustainable food consumption: Product choice or curtailment? Appetite, 91: 375-384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.055

Visschers, V.H.M., N. Wickli and M. Siegrist. 2016. Sorting out food waste behavior: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol., 45: 66-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.007

Vlaeminck, P. and S. Rousseau. 2018. Food waste reduction in the context of business models and value creation. J. Cleaner Prod., 185: 296-312.

Wang, D. and D.W. Sun. 2019. Food waste in China: An overview. J. Cleaner Prod., 224: 655-673.

Yildirim, H., R. Capone, A. Karanlik, F. Bottalico, P. Debs and H. El-Bilali. 2016. Food wastage in Turkey: An exploratory survey on household food waste. J. Nutr., 4: 483–489.

Zepeda, L. and J. Li. 2017. Characteristics of food away from home and food at home purchases. Food Policy, 66: 31-39.

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?