Food Analysis of Indian Gerbil (Tatera indica, Hardwicke, 1807) in Pothwar, Pakistan

Food Analysis of Indian Gerbil (Tatera indica, Hardwicke, 1807) in Pothwar, Pakistan

Amber Khalid1*, Amjad Rashid Kayani1, Muhammad Sajid Nadeem1, Muhammad Mushtaq1, Mirza Azhar Beg1 and Surrya Khanam2

1Department of Zoology, Pir Mehr Ali Shah, Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

2Department of Zoology, Women University Swabi.

ABSTRACT

Indian gerbil (Tatera indica) belongs to family Muridae, is considered an important agricultural pest and causes damage to the crops in Pakistan including Pothwar. Information about the diet of the rodents is prerequisite for the better management of pest species. Previous studies conducted on the diet of Indian gerbil were only based on field observations. This study provides information on the diet analysis of Indian gerbil through stomach contents. Samples were collected from different localities of Pothwar during different seasons. Stomachs were separated during autopsy. Slides from stomach contents were prepared and were compared with reference slides. Relative frequency of every food item observed in the stomach was calculated as percentages. The results showed that Indian gerbil predominately consumed plant matter in its diet (74.5%) along with animal matter (25.5%). Among plant matter, Triticum aestivum (wheat) was the major consumed item followed by Brassica campestris (mustard) and Arachis hypogaea (peanut). Sorghum bicolor (millet) and Vigna radiata (mong bean) was also consumed in small proportions. Pearson chi-square was used to calculate the significance difference among every food item and among seasons. Significant difference (p<0.05) was observed among consumption of different food items and among different seasons. Non- significant difference (p>0.05) was calculated between consumption of different food items in male and female rats. It is concluded that Indian gerbil damaged the cash crops of Pothwar. Therefore, preventive measures should be taken as part of integrated pest control program.

Article Information

Received 06 November 2021

Revised 20 February 2022

Accepted 15 March 2022

Available online 18 May 2022

(early access)

Published 14 March 2023

Authors’ Contribution

MAB designed the study. AK collected samples, performed analysis and wrote the manuscript. ARK supervised the study. MSN and MM reviewed the manuscript. SK helped in making slides.

Key words

Food analysis, Stomach, Indian gerbil, Tatera indica, Pest management, Pothwar, Pakistan

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/20211106131150

* Corresponding author: amberkhalid96@gmail.com

0030-9923/2023/0003-1193 $ 9.00/0

Copyright 2023 by the authors. Licensee Zoological Society of Pakistan.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Diets are significantly important to ascertain evolution, approaches of life history and ecological niche of the animals. Thus, the information on the food of animals is fundamentally important for many ecological studies (Kronfeld and Dayan, 1998). It is also necessary for the conservation of the species, concerns on the introduction of game animals and for nature conservation (Cole et al., 1995), and developing biological controls (Beg et al., 1994; Jimenez et al., 1994; Tobin et al., 1994). Availability of the food deliberates the population density of species (Ylonen et al., 2003) and reproductive capabilities of any individual (Htwe and Singleton, 2014). As far as the pest species are concerned, precise information of the diet is very important to develop effective targeted approaches. (Lathiya et al., 2008).

In Pakistan, rodents exert a serious limitation on agricultural production by causing extensive losses to cash crops as wheat, rice and sugarcane (Greaves et al., 1975; Greaves and Khan, 1975; Beg and Khan, 1977; Beg et al., 1978, 1979, 1988; Fulk et al., 1980; Fulk and Akhtar, 1981; Shafi and Khan, 1983; Ubaidullah et al., 1989). Indoors, house rat and house mouse depredate on stored grains and other food stuffs in rural and urban homes, grocery shops, wholesale markets and godowns (Ali, 1990; Khan, 1990; Mushtaq-ul-Hassan, 1993). Beg (1986) reported that murid rodents are profoundly important because of their impact on crops from sowing to harvest.

In Pothwar area rodents cause significant damage to the wheat and groundnut crops. Many species of small rodents like Bandicota bengalensis (lesser bandicoot rat), Nesokia indica (short tailed bandicoot rat), Tatera indica (Indian gerbil), Millardia meltada (soft furred field rat) and Mus musculus (house mouse) damage the crops in the Pothwar (Brooks et al., 1988; Hussain et al., 2003).

Diets of the rodents are generally characterized by different methods. One of the common adopted methods is stomach contents analysis or less common fecal analysis. Both the methods have some advantages and disadvantages. Some food items are completely digested in the stomach so fecal contents cannot reveal that material (Jeuniaux, 1961; Hansson, 1970; Neal et al., 1973; Dickman and Huang, 1988; Bergman and Krebs, 1993). Another method is stomach pumping of the rodents without sacrificing them (Kronfeld and Dayan, 1998). This study provides information through stomach contents about the diet of the Indian gerbil in Pothwar, Pakistan.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out from February, 2014 to January, 2016. After being snap trapped, samples were brought to the laboratory and were autopsied. Stomachs were cut from the esophagus and were preserved in the freezer. The stomach contents were removed and compared with the reference slides by adopting the procedure described below. In total, 42 stomachs were processed for the diet analysis. Empty or decomposed stomachs were discarded.

Preparation of reference slides

Different types of plant material were collected from the habitat of trapped individuals for the preparation of reference slides. These plant materials include rice (Oryza sativa), different stages and parts of wheat plant (Triticum aestivum) such as wheat leaves, roots, stem, spikes, and wheat grains, peanut (Arachis hypogaea), barley (Hordeum vulgare), apple (Malus domestica), maize (Zea mays), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), chana or chickpea (Cicer arietinum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), lentil or masoor (Lens culinaris), different parts of Brassica plant (Brassica campestris), dab grass (Imperata cylindrica), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) and lentil (Vigna mungo).

Plant materials were soaked overnight in water and were well ground in mortar and pestle. It was kept in bleaching solution of sodium hypochlorite for 20-25 min. Bleaching was followed by water wash, and then contents were kept in 30 % acetic acid for 20 min. After washing with distilled water, hematoxylin stain was added to the contents and kept for 15 min. The contents were kept on slide and air dried. At the end, Canada balsam was placed over it along with the cover slip to make it permanent (Jobling et al., 2001).

Photographs were taken by using a camera placed at the eyepiece of the light microscope. Insects were identified on the basis of the presence of chitin, portion of the body like legs, wings etc.

Preparation of stomach slides

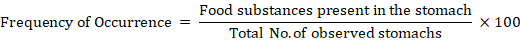

The stomach contents were poured in the petri dish and washed with the distilled water. Slides were made following the same procedure as discussed above except the process of grinding. The reason is that the stomach already digested the contents of the food. For each sample, three slides were made. Each slide was tagged with a unique id. Slides were compared with the reference slides for identification. Quantitative results were determined as a measure of the frequency of occurrence. Percentage of relative abundance was also calculated by using the formulae:

Pearson chi-square was used to find out the differences in different food items among different seasons and between two sexes. All differences with p> 0.05 were considered non-significant.

Results

The major diet of Indian gerbil comprised of plant matter (Table I). The plant matters constituted about 74.5% of the total diet and the arthropods constitute 25.5%. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of plant and animal matter (χ 2= 25, df= 1, p<0.05).

Among plant matters, wheat was the major consumed item (33.7%). Field mustard and peanut were consumed almost in equal proportion (16.9 % and 15.6 %, respectively). The consumption of millet was 7.8 %. Mong bean was also consumed in small proportion (0.5%).

Frequency of occurrence (F.O) of wheat was 53.6 % and was highest among all other food categories. F.O of field mustard was 27.2%. F.O of millet was 9.1%. F.O of peanut was 45.5 %. F.O of mong bean was 10.4%. F.O of arthropods was 60.2 %.

Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat compared to field mustard (χ 2= 5.6, df= 1, p<0.05), millet (χ2= 16.1, df= 1, p<0.05), peanut (χ2= 6.5, df= 1, p<0.05), and mong bean (χ2= 31.1, df= 1, p<0.05). Mong bean was significantly less consumed than field mustard (χ2= 14.2, df= 1, p<0.05), millet (χ2= 5.4, df= 1, p<0.05) and peanut (χ2= 13.2, df= 1, p<0.05). The order of food consumed by Indian gerbil was wheat > field mustard > peanut > millet > mong bean.

Seasonal variations in the diet of the Indian gerbil

Table I shows the seasonal fluctuations in the diet of Indian gerbil. Significant seasonal difference was observed in the consumption of all the food categories (p<0.05). In all the seasons, plant matter was consumed in different proportions. Among plant matters, wheat was consumed in all seasons.

Table I. Seasonal variations in the diet of the Indian gerbil.

|

Food items |

Spring (n=7) |

Summer (n=13) |

Autumn (n=1) |

Winter (n=21) |

All seasons (n=42) |

|||||

|

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

|

|

Arthropods/Insects |

28.6 |

7.9* |

69.2 |

46.7 |

- |

- |

24.5 |

22.8* |

60.2 |

25.5* |

|

Triticum aestivum (wheat) |

14.3 |

31.9a |

30.8 |

26.7a |

15.7 |

5.8a |

31.8 |

42.7a |

53.6 |

33.7a |

|

Brassica campestris (field mustard) |

57.1 |

53.1b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

13.6 |

18.0b |

27.2 |

16.9b |

|

Sorghum bicolor (millet) |

- |

-- |

- |

- |

43.2 |

85.3b |

4.5 |

8.0c |

9.1 |

7.8bc |

|

Arachis hypogaea (peanut) |

14.3 |

7.1c |

46.2 |

25.2a |

32.3 |

8.9c |

27.3 |

7.6cd |

45.5 |

15.6cd |

|

Vigna radiate (mong bean) |

- |

- |

6.2 |

1.4b |

- |

- |

4.5 |

0.9e |

10.4 |

0.5e |

|

Total plant matter |

85.7 |

92.1 |

83.2 |

53.3 |

91.2 |

100 |

81.7 |

77.2 |

145.8 |

74.5 |

F.O, frequency of occurrence; R.A, relative abundance of food.; n, No. of stomachs processed. * significantly different in arthropods/insects and plant matter, Values labeled with same alphabets are non-significantly (p>0.05) different in a column.

In spring season, the diet of Indian gerbil comprised of 92.1% of plant matter and 7.9% of arthropods. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of plant and animal matter (χ2= 70.5, df= 1, p<0.05). Among plant matter, field mustard was the major food item consumed by the gerbils (53.1 %).

Proportion of wheat was 31.9%. Millet and mong bean was not observed in any of the stomach sample of spring season. However, peanut was consumed in lower proportion (7.1%). F.O of field mustard was highest (57.1%). F.O of peanut was 14.3%. F.O of arthropods was 28.6%. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat compared to field mustard (χ2= 5.18, df= 1, p<0.05) peanut (χ2= 16.0, df= 1, p<0.05) and field mustard compared to peanut (χ2= 35.2, df= 1, p<0.05). The order of food consumption by Indian gerbil in spring season was field mustard > wheat > peanut.

In summers, the diet of Indian gerbil comprised of 53.3% of plant matter and 46.7% of animal matter or arthropods. Non-significant difference was observed in the consumption of plant and animal matter (χ2= 0.36, df= 1, p>0.05). Among plant matter, wheat was consumed in almost equal proportion of peanut (26.7 and 25.2% respectively). Relative abundance (R.A) of arthropods (46.7%) was the highest in the summer season; mong bean was also consumed in small proportions (1.4 %).

Field mustard and millet were not observed in any of the stomach contents. F.O of arthropods was the highest (69.2%) among all the food categories. F.O of wheat was 30.8%. F.O of peanut was 46.2%. F.O of mong bean was 6.2%. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat and mong bean (χ2= 24.1, df= 1, p<0.05), peanut and mong bean (χ2= 22.1, df= 1, p<0.05). Thus, the order of food consumption by Indian gerbil in summer season was wheat > peanut > mong bean.

In autumn season, millet was the chief staple food of Indian gerbil (85.3%). Wheat and peanut was also observed in small proportions (5.8% and 8.9%, respectively). In autumn, all other food categories were not observed in any of the stomachs. F.O of millet was 43.2%. F.O of wheat and peanut was 15.7 and 32.3, respectively. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat and millet (χ2= 65.5, df= 1, p<0.05) and millet and peanut (χ2= 61.4, df= 1, p<0.05). The order of food consumption by Indian gerbil in autumn season was millet > peanut > wheat.

In winters, the diet of Indian gerbil comprised of 77.2% of plant matter and 22.8% of arthropods. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of plant and animal matter (χ2= 29.1, df= 1, p<0.05). Among plant matter, wheat (42.7 %) was the mostly consumed item by Indian gerbil. Field mustard was the second major item (18.0%) found in the stomach of Indian gerbil in winter. Millet and peanut were also consumed in smaller proportions (8.0% and 7.6%, respectively). Mong bean was consumed in a very small amount (0.9 %). F.O of wheat was 31.8%. F.O of peanut was 27.3%. F.O of arthropods was 24.5%. F.O of field mustard, millet and mong bean was 13.6 %, 4.5% and 4.5% respectively.

Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat compared to field mustard (χ2= 17.2, df= 1, p<0.05), millet (χ 2= 33.1, df= 1, p<0.05), peanut (χ2= 33.1, df= 1, p<0.05) and mong bean (χ2= 50.1, df= 1, p<0.05). Field mustard was significantly more consumed than millet (χ2= 3.8, df= 1, p<0.05), peanut (χ2= 3.8, df= 1, p<0.05) and mong bean (χ2= 15.2, df= 1, p<0.05). Mong bean was less consumed than millet (χ2= 5.4, df= 1, p<0.05) and peanut (χ2= 5.4, df= 1, p<0.05). Non-significant difference was observed in the consumption of millet and peanut (p>0.05). The order of food consumption by Indian gerbil in winter season was wheat > field mustard > millet> peanut > mong bean.

Table II. Frequency of occurrence and relative abundance of different food items present in the stomach contents of male and female Indian gerbil.

|

Food items |

Male (n=25) |

Female (n= 19) |

||

|

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

F.O (%) |

R.A (%) |

|

|

Triticum aestivum (wheat) |

48.0 |

30.5 |

37.5 |

26.0 |

|

Brassica campestris (field mustard) |

24.0 |

20.1 |

31.0 |

18.0 |

|

Sorghum bicolor (millet) |

12.0 |

14.1 |

18.7 |

20.0 |

|

Arachis hypogaea (peanut) |

20.0 |

7.9 |

37.5 |

11.9 |

|

Vigna radiata (mong bean) |

10.4 |

0.5 |

-- |

-- |

|

Arthropods |

40.0 |

26.9 |

50.0 |

24.1 |

F.O, frequency of occurrence; R.A, relative abundance of food.; n, No. of stomachs processed.

Comparison of the diet of male and female Indian gerbil

Table II shows the comparison in the food consumption of male and female Indian gerbil In male samples, plant matter accounted for 73.1% and arthropods accounted for 26.9%. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of plant and animal matter (χ2= 21.16, df= 1, p<0.05). Wheat was the major food item consumed by male Indian gerbil. Other food items consumed were field mustard (20.1%), millet (14.1 %), peanut (7.9%), and mong bean (0.5%). Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat compared to millet (χ2= 6.42, df= 1, p<0.05), peanut (χ2= 13.56, df= 1, p<0.05) and mong bean (χ2= 28.12, df= 1, p<0.05). Field mustard consumption was significantly different than peanut (χ2= 5.14, df= 1, p<0.05) and mong bean (χ2= 17.1, df= 1, p<0.05).

The consumption of mong bean was significantly less than the consumption of millet (χ2= 11.26, df= 1, p<0.05) and peanut (χ2= 5.44, df= 1, p<0.05). The order of abundance of food consumed by male Indian gerbil was wheat> field mustard millet > peanut > mong bean

Female Indian gerbil consumed 75.9% of plant matter and 24.1% of arthropods. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of plant and animal matter (χ2= 27.04, df= 1, p<0.05) by female Indian gerbil. Among plant matter, wheat (26.0%) was the chief diet found. Arthropods (24.1%) were the second most consumed. Field mustard and millet were almost equally consumed (18.0% and 20.0%, respectively). Peanut was consumed in small amount (11.9%). Mong bean was not observed in any of the female samples. Significant difference was observed in the consumption of wheat and peanut. The order of food items consumed by female Indian gerbil was wheat > millet > field mustard > peanut. Non-significant difference was observed in the consumption of different food categories between male and female samples (p>0.05).

Discussion

The study on the diet of an animal is significantly important because food gives important information for ecological research such as conservation, evolution, relationship between animal and its environment. Food is vital for the maintenance of body functions and reproduction. Information obtained from stomach analysis on rodents is the main ecological parameter to study the food preference, habitat association, seasonal fluctuation and the pest status (Campos et al., 2001).

In present study, the stomach analysis showed that the major diet constitutes of plant matter in all the seasons. However, the frequency of each food item varied seasonally. Among plant matter, wheat was the major food item. Animal matter or arthropods were also consumed.

In spring season, field mustard was the major plant matter found in the stomach. This was due to the availability of particular food tem in the spring season. In summer season, the major diet of Indian gerbil consisted of animal matter i.e., insects were consumed in this season. Peanut was also found due to the availability. In autumn season, millet was found in the large proportion in the stomach contents, which indicates that it was most abundant in the season. In winter season, wheat grains were consumed in large amount. The present study thus strongly suggests that Indian gerbil is an opportunistic forager. There is considerable fluctuation in the consumption of different food items, which is in conformity with the variations in the vegetation in the eco-system reflecting the availability of different food items. This could be an indication of their success in wide distribution.

No significant difference was found in the consumption of different food categories among male and female individuals. The difference in the diet of male and female would occur when there would be shortage of particular food item in the environment that rarely happens in the stable environment (Clark, 1980).

Conclusion

In conclusion, Indian gerbil is an opportunistic forager. It eats whatever is available. However, seasonal fluctuations were observed in the diet pattern of this pest species. Moreover, this study could be helpful in the formation of bait for this species, which is prerequisite for the management of the pest species.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted under the financial assistance of Pakistan Science Foundation through Grant No. PSF/Res/P-PMAS.AAUR/Bio.446.

Ethics approval

This research study was approved by the Ethical committee of PMAS Arid Agriculture University.

Statement of conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Ali, A., 1990. Population density and reproduction in house rat (Rattus rattus) living in residential houses and grain shops at Faisalabad city. M.Sc. thesis, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Beg, M.A., 1986. Ecology of rats and mice in the agroecosystem of Punjab. Proc. Pakistan Congr. Zool., pp. 1-13.

Beg, M.A., and Khan, Y.M., 1977. Rodent damage to wheat crop in Faisalabad District. Pak. J. agric. Sci., 14: 37-44.

Beg, M.A., Khan, A.A., and Begum, F., 1979. Rodent problem in Sugarcane fields of Central Punjab. Pak. J. agric. Sci., 16: 105-110.

Beg, M.A., Khan, A.A., and Yasin, M., 1978. Some traditional damage to the wheat in Central Punjab. Pak. J. agric. Sci., 15: 105-106.

Beg, M.A., Ubaidullah, M., Anwar, M., and Khan, A.A., 1988. Wheat losses during harvesting operation. Pak. J. agric. Sci., 25: 253-254.

Beg, M.A., Khan, A., and Mushtaq-Ul-Hassan, M., 1994. Food habits of Millardia meltada (Rodentia, Muridae) in the croplands of central Punjab (Pakistan). Mammalogy, 58: 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1515/mamm.1994.58.2.235

Bergman, C.M., and Krebs, C.J., 1993. Diet overlap of collared lemmings and tundra voles at Pearce Point, Northwest Territories. Can. J. Zool., 71: 1703-1709. https://doi.org/10.1139/z93-241

Brooks, J. Ahmad, E., and Hussain. I., 1988. Damage by vertebrate pests to groundnut in Pakistan. In: Proc. 13th vertebrate pest. conference (eds. A.G. Crabb and R.E. Marsh). University of California, Davis, CA, USA, 129-133.

Campos, C., Ojeda, R., Monge, S., and Dacar, M., 2001 Utilization of food resources by small and medium-sized mammals in the Monte Desert biome, Argentina. Aust. Ecol., 26: 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-9993.2001.01098.x

Clark, D.A., 1980. Age and sex-dependent foraging strategies of a small mammalian omnivore. J. Anim. Ecol., 49: 549-563. https://doi.org/10.2307/4263

Cole, F.R., Loope, L., Medeiros, A.C., Raikes, J.A., and Wood, C.S., 1995. Conservation implications of introduced game birds in high-elevation Hawaiian shrubland. Conserv. Biol., 9: 306-313. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.9020306.x

Dickman, C., and Huang, C., 1988. The reliability of fecal analysis as a method for determining the diet of insectivorous mammals. J. Mammal., 69: 108-113. https://doi.org/10.2307/1381753

Fulk, G., and Akhtar, M., 1981. An investigation of rodent damage and yield reduction in rice. Int. J. Pest Manage., 27: 116-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670878109414176

Fulk, G., Smiet, A., and Khokhar, A., 1980. Movements of Bandicota bengalensis (Gray 1873) and Tatera indica (Hardwicke, 1807) as revealed by radio telemetry. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc., 76: 457-462.

Greaves, J.H., and Khan, A.A., 1975. A survey of the rodent attack on standing rice in the Punjab in 1974. FAO working paper Pak/71/554. pp. 4.

Greaves, J.H., Fulk, G.W., and Khan, A.A., 1975. Preliminary investigation of the rice-rat problem in lower Sindh. In: All India Rodents Seminar, Ahmedabad (India) (eds. K. Krishnamutry, G.C. Chaturvedi and Prakash). September. Sidhpur: Rodent Control Project. pp. 1-5.

Hansson, L., 1970. Methods of morphological diet micro-analysis in rodents. Oiko, 21: 255-266. https://doi.org/10.2307/3543682

Htwe, N.M., and Singleton, G.R., 2014. Is quantity or quality of food influencing the reproduction of rice-field rats in the Philippines? Wildl. Res., 41: 56-63. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR13108

Hussain, I., Cheema, A., and Khan, A., 2003. Small rodents in the crop ecosystem of Pothwar Plateau, Pakistan. Wildl. Res., 30: 269-274. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR01025

Jeuniaux, C., 1961. Chitinase: An addition to the list of hydrolases in the digestive tract of vertebrates. Nature, 192: 135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/192135a0

Jimenez, R., Hodar, J., and Camacho, I., 1994. Diet of the woodpigeon (Columba palumbus) in the south of Spain during late summer. Folia Zool., 43: 163-170.

Jobling, M., Coves, D., Damsgard, B., Kristiansen, H.R., Koskela, J., Petursdottir, T.E., Kadri, S., and Gudmundsson, O., 2001. Techniques for measuring feed intake. In: Food intake in fish (eds. D. Houlihan, T. Boujard and M. Jobling). Blackwell Science Ltd. pp. 51-52.

Khan, A.A., 1990. Population density and reproduction of house rats living in some sweets and grocery shops in Faisalabad city. M.Sc. thesis, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Kronfeld, N., and Dayan, T., 1998. A new method of determining diets of rodents. J. Mammal., 79: 1198-1202. https://doi.org/10.2307/1383011

Lathiya, S., Ahmed, S., Pervez, A., and Rizvi, S., 2008. Food habits of rodents in grain godowns of Karachi, Pakistan. J. Stored Prod. Res., 44: 41-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2007.06.001

Mushtaq-ul-Hassan, M., 1993. Population dynamics, food habits, and economic importance of house rat (Rattus rattus) in villages and farm houses of central Punjab, Pakistan. PhD thesis, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Neal, B., Pulkinen, D., and Owen, B., 1973. A comparison of faecal and stomach contents analysis in the meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus). Can. J. Zool., 51: 715-721. https://doi.org/10.1139/z73-105

Shafi, M.M., and Khan, A.A., 1983. Rat damage to sugarcane crop and its control. Prog. Farm., 3: 18-22.

Tobin, M., Koehler, A., and Sugihara, R., 1994. Seasonal patterns of fecundity and diet of roof rats in a Hawaiian macadamia orchard. Wildl. Res., 21: 519-525. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR9940519

Ubaidullah, M., Baig, M., Khan, A., and Shahwar, D., 1989. Density of rats and mice burrows and losses in harvested wheat fields. Pak. J. agric. Sci., 26: 107-117.

Ylonen, H., Jacob, J., Runcie, M.J. and Singleton, G.R., 2003. Is reproduction of the Australian house mouse (Mus domesticus) constrained by food? A large sclae field experiment. Popul. Ecol., 135: 372-377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1207-6

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?