An Assessment of Off-Season Vegetables Production in District Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Research Article

An Assessment of Off-Season Vegetables Production in District Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Ejaz Ul Haq, Urooba Pervaiz*, Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and Ayesha Khan

Department of Agricultural Extension Education and Communication, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | Agricultural production has been increased due to adoption of modern agriculture techniques and practices. This study analyzed off-season vegetables production in District Peshawar with the objectives to highlight the problems faced by farmers in cultivation of off-season vegetables, evaluate the yield and income of off-season vegetables and the role of extension workers in creating awareness among farming community regarding off-season vegetables. Data were collected from 60 sample respondents from three circles (Mattani, Peshawar and Tarnab) through pre-tested and well-structured interview schedule during February- March, 2020. The results showed that 48.3% farmers were motivated by extension staff towards tunnel technology, only 6.7% farmers got training regarding tunnel farming, 70% respondents reported that extension worker visited their field once a year. The study concluded that though extension worker visited farmers’ field but the frequency was very low and very limited trainings were given to the farmers regarding tunnel farming in the study area. Results of paired sample t- test showed that cost of tomato and bitter-gourd in tunnel is higher as compared to cultivation of these vegetables in field, while the yield and net-income obtained in tunnel was also high. The study also concludes that tomato cultivated in tunnel is more profitable as compared to bitter-gourd. Major constraints faced by farmers in tunnel cultivation were high cost of installation and inputs, unavailability of certified seed, fertilizers and pesticides, lack of technical knowledge, lack of cold storage, high cost of transportation, pest and disease attack, defective marketing and lack of credit facility. The study recommends that farmers should be encouraged and facilitated to adopt tunnel farming technology as it is the best method to grow off-season vegetables and for yields, both the field staff of extension department and farmers must be provided training for development of tunnels and package of production timely. Government should facilitate to establish agriculture insurance and provide subsidy to farmers (in energy, fertilizer, seed etc).

Received | November 10, 2020; Accepted | July 19, 2022; Published | October 09, 2022

*Correspondence | Urooba Pervaiz, Department of Agricultural Extension Education and Communication, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; Email: drurooba@aup.edu.pk

Citation | Haq, E.U., U. Pervaiz, M.Z. Khan and A. Khan. 2022. An assessment of off-season vegetables production in district Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 38(4): 1443-1451.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2022/38.4.1443.1451

Keywords | Tunnel farming, Extension worker, Tomato, Bitter gourd, Technical knowledge

Copyright: 2022 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Pakistan is an agricultural country, where majority of the people directly or indirectly depends on agriculture, unfortunately agricultural productivity remains behind the potential level in Pakistan (Aziz et al., 2013). Agricultural production must be increased by adopting modern technologies in order to feed rapid growing population (Al-Sharafat, 2012).

Research, extension, and farmers are believed as the three main components of agricultural development. Farming community and the researchers were linked through extension personal (Ahmad, 2005). But in Pakistan unfortunately, this co-ordination does not exist up to the mark (Sanaullah et al., 2020). Agricultural extension has dual responsibility, on one hand it disseminate suitable agricultural techniques and ideas among the target farming community and make them able to fully utilize these techniques which will help them in improving/increasing their farm productivity, and on the other hand it bring back farmers’ problem to the research station for solution (Sadaf et al., 2005). Moreover, agriculture extension offers suitable farming methods and concepts for farming community to introduce them into their farming techniques (Pervaiz et al., 2020). Therefore, the extension staff not only helps farmers to enhance their farm production and plan a harvest schedule, but also encourage them to use enhanced cultivation tools and implement contemporary farming practices according to their socio-economic status (Al-Sharafat, 2012).

Vegetables are the main constituents of our diet (Mishra and Kumar, 2012). The demand of dietary vegetables rises with increase in population rate, but unfortunately, due to traditional methods of farming; the farmers are not able to produce up to the mark (Kang et al., 2013). In order to overcome hunger and food insecurity it is the dire need of the day to adopt modern agricultural techniques and the best idea is to grow vegetables in off-season (Tahir and Altaf, 2013).

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa there are many varieties of vegetables (tomato, chilies, bitter gourd, bottle gourd, cucumber sweet pepper and pepper) that are cultivated in few parts each year (Ishaq et al., 2003). In general, it is not possible to grow winter vegetables in summer season. Summer vegetables are suitable for planting in a plastic tunnel or in a greenhouse in cold climates. The difference between the cultivation of plastic tunnels and the green house is clear. Greenhouse is equipped with electricity and automatic ventilation and heating system. The humidity, light, rain, wind and the proportion of different essential gases can be controlled successfully within the greenhouse, whereas high tunnels has passive ventilation for air exchange. It must be taken into account that the plastic should be covered so that there is no cold air in the tunnel; the temperature obtained during the day can work at night (Janke et al., 2017). In addition, inside the tunnel, synthetic conditions are created, which help the vegetable to grow (Iqbal et al., 2014). In Pakistan expensive vegetables were available from Sindh Province before tunnel farming (Muhammad et al., 2014). While, in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa tunnel farming is started for the vegetables sold for this luxurious dough and cultivation is increasing (Imran et al., 2015). Moreover, 93% of landowners are small farmers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, so if we make them an exhausted seasonal farming exchange, then our province will grow in the vegetable cultivation (Ishaq et al., 2003).

Off-season cultivation of vegetables is very helpful to uplifting farmers’ financial conditions. The return of the off-season vegetables is higher than the traditionally grown normal season vegetables. On one hand maximum yield will be obtain from tunnel technology under control temperature, and humidity help in maintaining land fertility, better water conservation and protection from rodents and animals (Foord, 2004). On the other hand, vegetables grown in tunnels are highly susceptible to pests and disease attack, and proper care should be taken to overcome this problem (Kabir et al., 1996; Prajapati, 2007). Therefore, an attempt had made to analyze off-season vegetables production in District Peshawar with the objectives to highlight the problems faced by farmers in cultivation of off-season vegetables, evaluate the yield and income of off-season vegetables and the role of extension workers in creating awareness among farming community regarding off-season vegetables.

Materials and Methods

The universe of the study was District Peshawar. The total reported area of the district is 126,661 hectares and total cultivated area is 78,854 hectares. District Peshawar is divided into five Circles i.e., Academy Circle, Mattani Circle, Naguman Circle, Tarnab Circle and Peshawar Circle. Three out of five circles i.e. Peshawar, Tarnab and Mattani were selected purposely based on tunnel technology adoption for off-season vegetables cultivation. A list of all the farmers in the selected circles was prepared with the help of Agriculture Officer and all those respondents who were cultivating off-season vegetables or adopted tunnel technology as well as growing the same vegetables in season were interviewed. Total 60 respondents were interviewed for this study, 15 respondents were interviewed from Mattani Circle, 20 respondents from Peshawar Circle and 25 respondents were interviewed from Tarnab Circle. It is important to note that the respondents who cultivated the same vegetable both in tunnel and season were selected. All these 60 respondents were cultivating tomato and bitter gourd. Primary data were collected from sample respondent through face to face interview. The data were presented in percentages. Paired sample t-test was applied to find out the mean difference of cost, yield and income of vegetables in field and tunnel.

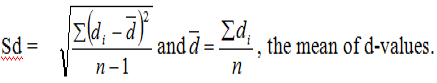

Paired sample T-test

To envisage the difference between the mean income before and after training, a pair t-test was applied to check the significant difference at 5% level of probability. The pair t-test for convenience is given as:

Where; d= difference between two sample observations (before and after the membership); n= number of pairs; Sd= standard deviation.

Results and Discussion

Area under off-season vegetables

Vegetables are a regular dietary necessity reliable and good source of vitamins, carbohydrates and minerals (Imran et al., 2015). Off-season vegetables farming is the only option that farmers can increase their income and produce/able to supply quality vegetables in the market in scarce condition in a situation where lack of vegetables processing industry and storage facilities are common in a country (Iqbal et al., 2014).

Data regarding area under off-season vegetables were presented in Table 1. Majority of the respondents (80%) cultivated vegetables up to 0.5 acre under tunnel, while 20% respondents cultivated vegetables at 0.6-1 acre area in tunnels. These results are in contrast with Muhammad et al. (2014) who reported that 58.3% respondents increased their area under tunnel vegetables up to 1 acre.

Table 1: Distribution of respondents on the basis of area under off-season vegetables.

|

Circle |

Area under off-season vegetables |

||

|

Up to 0.5 acre frequency (%) |

0 .6-1 acre frequency (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

14 (23.3) |

1 (1.7) |

15 |

|

Peshawar |

13 (21.7) |

7 (11.7) |

20 |

|

Tarnab |

21 (35) |

4 (6.7) |

25 |

|

Total |

48 (80) |

12 (20) |

60 |

Source: Field survey, 2020.

Type of tunnel

Tunnel farming has been going popular day by day by producing more and quality production to farmers (NBP, 2013). Off-season vegetables can produce high yield and more production as compared to on-season (Muhammad et al., 2014). Off-season vegetables in tunnels are mostly expensive and profitable to farmers (Schrenemachers et al., 2016). Mostly there are three types of tunnel farming i.e. (1) High tunnel (2) Walk-in tunnel (3) Low tunnel.

Table 2 showed that 80% respondents cultivated vegetables in high tunnel, while 20% respondents used to cultivate vegetables in walk-in tunnel, while none of the respondents cultivated vegetables in low tunnel. Farmers only cultivate seedlings and germinate nursery in low tunnel. Our results are in line with Janke et al. (2017) who concluded that high tunnels have been used in United States for more than 50 years, and growers were encouraged to adopt high tunnels through government private cost-share programme.

Table 2: Distribution of respondents on the basis of type of tunnel.

|

Circle |

Tunnel type |

|||

|

High tunnel frequency (%) |

Walk-in tunnel frequency (%) |

Low tunnel frequency (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

9 (15) |

6 (10) |

0 (0) |

15 |

|

Peshawar |

18 (30) |

2 (3.3) |

0 (0) |

20 |

|

Tarnab |

21 (35) |

4 (6.7) |

0 (0) |

25 |

|

Total |

48 (80) |

12 (20) |

0 (0) |

60 |

Source: Field survey, 2020.

Vegetables cultivated in tunnels

Vegetables are rich sources of minerals and vitamins. Vegetables can play an essential role in human nutrition. Vegetables maintain our healthy activities and gives help in prevention of dangerous diseases (Kang et al., 2013). In the study area different vegetables were grown in tunnels such as tomato, bitter gourd, squash, and ladyfinger etc. But most of the farmers cultivated tomato and bitter gourd both in season and off-season, so data were collected from those farmers who cultivated these vegetables.

Table 3 shows that majority of the respondents i.e. 61.7% were cultivating both vegetables, such as tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) and bitter gourd (Momordica charantia), 23.3% of the respondents reported that they cultivated only tomato, while 15% respondents were taking interest to cultivate bitter gourd in tunnel.

Table 3: Distribution of respondents on the basis of vegetables cultivated in tunnel.

|

Circle |

Vegetables cultivated in tunnel |

|||

|

Tomato frequency (%) |

Bitter gourd frequency (%) |

Both 1and 2 frequency (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

1 (1.7) |

4 (6.7) |

10 (16.7) |

15 |

|

Peshawar |

5 (8.3) |

2 (3.3) |

13 (21.7) |

20 |

|

Tarnab |

8 (13.3) |

3 (5) |

14 (23.3) |

25 |

|

Total |

14 (23.3) |

9 (15) |

37 (61.7) |

60 |

Source: Field survey, 2020.

Source of motivation of tunnel farming

Farmer needs technical assistance and different suggestions regarding farming practices, such as seeds, fertilizers, pesticides and money required for various inputs (Sanaullah et al., 2020) to improve their socio-economic level (Chaudhary, 2006). Gecho and Punjabi (2011) mentioned that most of the farmers did not follow the extension recommendations especially seed rate, type of fertilizers and rate of application.

Data regarding source of motivation towards tunnel farming were presented in Table 4 show that 48.3% of the respondents were motivated to adopt tunnel farming by agriculture extension staff, 36.7% were motivated by fellow farmers, while only 15% of the respondents in the study area adopted tunnel farming themselves, due to more productive and profitable.

Table 4: Distribution of respondents on the basis of source of motivation in the study area.

|

Circles |

Source of motivation towards tunnel farming |

|||

|

Own frequency (%) |

Fellow farmers frequency (%) |

Agric. ext. staff frequency (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

0 (0) |

2 (3.3%) |

13 (21.7) |

15 |

|

Peshawar |

5 (8.3) |

14 (23.3) |

1 (1.7) |

20 |

|

Tarnab |

4 (6.7) |

6 (10) |

15 ( 25) |

25 |

|

Total |

9 (15) |

22 (36.7) |

29 (48.3) |

60 |

Source: Field survey, 2020.

Provision of training regarding tunnel farming

Training is mostly useful in every field of life. A lot of knowledge and experiences can get from training in every field of life (Sanaullah and Pervaiz, 2019). A trained person can be easily motivated towards adoption. Major components of agriculture extension department are provision of new and updated knowledge, timely information and trainings (Jat et al., 2012; Farooq et al., 2017).

Data regarding trainings of farmers regarding tunnel farming were given in Table 5. Out of the total 60 respondents majority i.e. 93.3% reported that they never get any training regarding tunnel farming, while only 6.7% of the respondents claimed that they got training from agriculture extension staff regarding tunnel farming. These results are in contrast with Pervaiz et al. (2018) who reported that 100% of the respondents got training regarding improved tomato technologies in District Mardan. This may be the fact that they interviewed all those respondents who got training from extension department during March-April 2016. While Sanaullah and Pervaiz (2019) concluded that yield of maize, tomato, wheat, okra and onion was increased after extension trainings through the adoption of improved farming practices.

Table 5: Distribution of respondents on the basis of trainings provided regarding tunnel farming.

|

Circle |

Training regarding tunnel farming |

||

|

Yes frequency (%) |

No frequency (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

2 (3.3) |

13 (21.7) |

15 |

|

Peshawar |

1 (1.7) |

19 (31.7) |

20 |

|

Tarnab |

1 (1.7) |

24 (40) |

25 |

|

Total |

4 (6.7) |

56 (93.3) |

60 |

Source: Field survey, 2020.

Extension workers visits to farmers’ field

For extension workers field visits are very important in order to transfer practical and timely information about different farming problems for farmers (Sanaullah et al., 2020). Farmers discussed various field problems with extension workers through a proper channel. Extension workers are change agent and it is the responsibility of extension workers to visits field in order to introduce and share new invention with farmers and solve the problems of farming community (Pervaiz et al., 2018). It is obvious that frequent extension-farmers contact significantly affect farmers’ exposure about modern agricultural information (Abrhaley, 2007).

Table 6 indicate results about frequency of extension workers’ visits to farmers’ field, 70% of the respondents stated that extension workers visits our fields once in a year, while 30% of them argued that extension workers visits our farm on monthly basis. The farmers were not satisfied from such type of visits that’s were carried out once in a year, because farmers want timely and updated information about different levels of farming practices. Our results are in contrast with Pervaiz et al. (2018) who reported that 53% of respondents claimed monthly visits of extension staff.

Table 6: Distribution of respondents on the basis of frequency of extension workers visits to farmers’ field.

|

Circle |

Frequency of extension workers visits to field |

||

|

Monthly frequency (%) |

Yearly frequency (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

4 (6.7) |

11 (18.3) |

15 |

|

Peshawar |

5 (8.3) |

15 ( 25) |

20 |

|

Tarnab |

9 (15) |

16 (26.7) |

25 |

|

Total |

18 (30) |

42 (70) |

60 |

Source: Field survey, 2020.

It is clear from the results that in the study area extension-farmers contact existed because all the respondents had some contact with the extension staff, but the frequency of farmer-extension contact is very low, which needs to be increased.

Cost of production of tomato and bitter gourd in tunnel and field

Total cost is the actual expenses, which are used to obtain certain level of good results during cultivation of tomato in field (Jat et al., 2012). The expenditures were varying from farmer to farmers regarding their field. Cost depends on various situation of farm size, different inputs supply such as fertilizers, pesticides, seeds and cost of labors etc. at tunnel farm level.

To find out mean significant difference of cost of tomato in field and cost of tomato in tunnel, paired sample t-test was applied and the findings were presented in Table 7. This cost includes cost of installation of tunnel, land preparation, labour, seeds, fertilizers, pesticides etc. The results showed that there was a highly significant (p<0.01) difference between cost of tomato in field and cost of tomato in tunnel. On average, mean difference was recorded (38,183.3), which means that cost of tomato in tunnel is more than the cost of tomato in field. Our results are in line with Janke et al. (2017) who concluded that the cost of growing tomato in tunnel is eight times higher as compared to open field.

The results in Table 7 also showed that there was a highly significant (p<0.01) difference between cost of bitter gourd in field and cost of bitter gourd in tunnel. On average, mean difference was recorded (39,150.0), which means that cost of bitter gourd in tunnel is more than the cost of bitter gourd in field. Our results were in line with that of Khan and Khan (2020) who analyzed tunnel farming in enhancing productivity of off-season vegetables and concluded that yield obtained from tunnel was significantly higher than seasonal vegetables, but the cost of inputs and structure installation was also higher in tunnel farming as compared to seasonal vegetables.

Yield of tomato and bitter gourd in tunnel and field

To find out mean significant difference of yield of tomato in field and tunnel, paired sample t-test was applied and the findings were presented in Table 8. The results showed that there was a highly significant difference between yield of tomato in field and yield of tomato in tunnel. On average, mean difference was recorded (7356.667), which means that yield of tomato in tunnel is more than the yield of tomato in field. Our results were in line with that of Khan and Khan (2020) who analyzed tunnel farming in enhancing productivity of off-season vegetables and concluded that yield obtained from tunnel was significantly higher than seasonal vegetables. Table also indicated that highly significant difference between yield of bitter gourd in field and yield in tunnel was found. On average, mean difference was recorded (3820.833), which means that yield of bitter gourd in tunnel is more than the yield of bitter gourd in field.

Table 7: Paired sample t-test comparison of cost of tomato and bitter gourd in field and tunnel.

|

Variable |

Cost Rs/kanal in Tunnel |

Cost Rs/kanal in Field |

Mean difference |

t value |

p value |

||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||||

|

Tomato |

61033.3 |

2024.98 |

22850.0 |

1603.22 |

38183.3 |

143.40 |

0.000*** |

|

Bitter-gourd |

61916.67 |

2027.04 |

22766.67 |

1499.90 |

39150.0 |

144.00 |

0.000*** |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2020; *** 99% confidence interval.

Table 8: Paired sample t-test comparison of yield (Kg/acre) of tomato in field and tunnel.

|

Variable |

Yield Kg/acre in tunnel |

Yield Kg/acre in field |

Mean difference |

t value |

p value |

||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||||

|

Tomato |

15863.3 |

1280.48 |

8506.6 |

758.64 |

7356.66 |

40.583 |

0.000*** |

|

Bitter-gourd |

5018.33 |

976.285 |

1197.50 |

46.418 |

3820.833 |

31.331 |

0.000*** |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2020; *** 99% confidence interval.

Table 9: Paired sample t-test comparison of net-income of tomato in field and tunnel.

|

Variable |

Net-income (Rs) in tunnel |

Net-income(Rs) in field |

Mean difference |

t-value |

p-value |

||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||||

|

Tomato |

581333.3 |

113741.7 |

213833.3 |

23186.17 |

367500.0 |

28.301 |

0.000*** |

|

Bitter-gourd |

327583.3 |

26078.29 |

60466.67 |

2789.002 |

267116.6 |

80.853 |

0.000*** |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2020; *** 99% confidence interval.

Net-income obtained from tomato and bitter gourd in field/season and tunnel

The whole process had been carried out for economic gain. Net-income means purely saved profits. Proper methods and procedure can be adopted for producing high yield and income in tunnel technology. Majority of the farmers adopted this technology gradually for better income.

To find out mean significant difference of net-income of tomato in field and net-income of tomato in tunnel, paired sample t-test was applied and the findings were presented in Table 9. The results showed that there was a highly significant difference between net-income of tomato in field and net-income of tomato in tunnel. On average, mean difference was recorded 367,500.0 Rs/acre, which means that net-income of tomato in tunnel is more than the net-income of tomato in field. The results also showed that there was a highly significant difference between net-income of bitter gourd in field and net-income of bitter gourd in tunnel. On average, mean difference was recorded 267,116.6 Rs/acre, which means that net-income of bitter gourd in tunnel is more than the net-income of bitter gourd in field.

We conclude that the net income of tomato and bitter gourd in tunnel is higher as compared to the net income of these vegetables in field. We also conclude that tomato growing in tunnel is more profitable than that of bitter gourd.

Problems faced by respondents in tunnel farming

Farmers are well experienced and practically observed all the field operations (Jat et al., 2012: Sanaullah et al., 2020). Farmers have a lot of knowledge about farming practices. They know different techniques to increase their production and aware to overcome different complex problems (Siddiqui and Mirani, 2012).

Data regarding the problems faced by farmers in cultivation of off-season vegetables in the study area were presented in Table 10, indicated that majority (95.1%) of the respondents reported high cost of installation and inputs as a major problem in cultivation of off-season vegetables and suggested that government should provide and construct a tunnel and their materials i.e. Iron rods, wires, woods and PVC pipes etc. Disease problem was reported by 95.1% of the respondents. While 91.7% emphasized that lack of technical knowledge, certified seeds, fertilizers and pesticides as a main problem, 76.6% of the respondents reported defective marketing as a problem. Lack of credit facility was reported by 41.7%, while 40% respondents reported lack of cold storage as one of the problem regarding off-season vegetables cultivation in the study area.

Table 10: Distribution of respondents on the basis of problems regarding tunnel farming.

|

Circles |

problems faced by respondents |

|||||||

|

Lack of technical knowledge f (%) |

Disease problem f (%) |

Defective marketing of produce f (%) |

Lack of certified seeds fertilizers and pesticides f (%) |

High cost of installation and inputs f (%) |

Lack of credit f (%) |

Lack of cold storage f (%) |

Total |

|

|

Mattani |

14 (23.3) |

13 (21.7) |

15(25) |

14 (23.3) |

13 (21.7) |

6 (10) |

6 (10) |

88 |

|

Peshawar |

18 (30) |

19 (31.7) |

13(2.17) |

18 (30) |

19 (31.7) |

9 (15) |

9 (15) |

116 |

|

Tarnab |

23 (38.3) |

25 (41.7) |

18(30) |

23 (38.3) |

25 (41.7) |

10 (16.7) |

9(15) |

146 |

|

Total |

55 (91.7) |

57 (95.1) |

46(76.6) |

55 (91.7) |

57 (95.1) |

25 (41.7) |

24(40) |

350 |

Source: Field survey, 2020; Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The study concluded that though extension worker visited farmers’ field but the frequency was very low and very limited trainings were given to the farmers regarding tunnel farming in the study area, this shows negligence of extension department. Furthermore, it was concluded that cost of tomato and bitter gourd in tunnel is higher as compared to cultivation of these vegetables in field, while the yield and net-income obtained in tunnel was high. The study concluded that tomato cultivated in tunnel is more profitable as compared to bitter gourd. The study also concluded that major constraints faced by farmers in tunnel cultivation were high cost of installation and inputs, unavailability of certified seed, fertilizers and pesticides, lack of technical knowledge, lack of cold storage, high cost of transportation, disease attack, defective marketing and lack of credit facility.

The study recommends that government may help off-season vegetables growers to construct the tunnel on share-based programme. Farmers should be encouraged and facilitated to adopt tunnel farming technology as it is the best method to grow off season vegetables and better yield. Training must be provided to both the field staff of Agriculture Extension and farmers for the development of tunnels and its package of production.

Novelty Statement

Off-season cultivation of vegetables is very helpful to uplift farmers’ financial conditions. The return of the off-season vegetables is higher than the traditionally grown normal season vegetables. On one hand, maximum yield will be obtain from tunnel technology under control temperature and humidity. On the other hand, vegetables grown in tunnels are highly susceptible to pests and disease attack.

Author’s Contribution

Ejaz Ul Haq: Collected the field data, and performed the analysis.

Urooba Pervaiz: Developed the main idea, wrote the manuscript and performed the analysis, and was the corresponding author.

Muhammad Zafarullah Khan: Helped in editing the manuscript.

Ayesha Khan: Helped in editing of manuscript and perform language correction.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Abrhaley, G., 2007. Farmers’ perception and adoption of integrated striga management technology in Tahtay Adiabo Woreda, Tigray, Ethopia. M.Sc. thesis submitted to School of Graduate studies, Haramaya University Ethopia. pp.54.

Ahmad, M., 2005. Evaluation of the working of extension field staff for the development of farming community. Pak J. Agric. Sci., 29(2): 40-47.

Ahouangninou, C., T. Martin and P. Edorh. 2012. Characterization of health and environmental risks of pesticide use in market-gardning in the rural city of Tori-Bossito in Benin, West Africa. J. Environ. Prot., 3: 241-248. https://doi.org/10.4236/jep.2012.33030

Al-Sharafat, A. 2012. Effectiveness of agricultural extension activities. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci., 7(2): 194-200. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajabssp.2012.194.200

Asfar, N. and M. Idrees. 2019. Farmers’ perception of agricultural extension services in dissementing climate change knowledge. Sarhad J. Agric., 35(3): 942-947.

Aziz, I., T. Mahmood and R. Islam. 2013. Effect of long term no-till and conventional tillage practices on soil quality. Soil Tillage Res., 131: 28-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2013.03.002

Chaudhary, K.M., 2006. An analysis of alternative extension approaches to technology dissemination and its utilization for sustainable agricultural development in Punjab, Pakistan. Ph. D thesis, Department of Agricultural Extension, University of Agriculture Faisalabad. pp. 55-56.

Farooq, S., S. Muhammad, K.M. Chaudhary and I. Ashraf. 2017. Role of print media in the dissemination of agricultural information among farmers. Pak. J. Agric. Sci., 44(2): 378-380.

Foord, K., 2004. High tunnel marketing and economics. Regents of the Univ. of Minnesota. 21 November 2010. http://www.extension.umn.edu/distribution/horticulture/components/M1218-12.

Gecho, Y. and N.K. Punjabi. 2011. Determinants of adoption of improved maize technology in Domat Gale, Wolaita, Ethopia. Rajasthan J. Ext. Educ., 19: 1-9.

Imran, M.U., F. Maula, M. Vacirca, S. Farfaglia and M.N. Khan. 2015. Introduction and promotion of off-season vegetables production under natural environment in hilly area of Upper Swat-Pakistan. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 5(11): 42-46.

Iqbal, M., 2009. A study into the working relationship among various components of training and visit programmes in D.G. Khan District. Unpublished M. Sc (Hons) thesis, Univ. of Agric. Faisalabad, Pakistan. pp. 16.

Iqbal, M., F.H. Sahi, T. Hussain, N.K. Aadal, M.T. Azeem and M. Tariq. 2014. Evaluation of comparative water use efficiency of furrow and drip irrigation system for off-season vegetables under plastic tunnel. Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci., 7: 185-190.

Ishaq, M.S., G. Sadiq and S.H. Saddozai. 2003. An estimation of cost and profit functions for off-season cucumber produce in District Nowshera-Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 19(1): 155-161.

Janke, R.R., M.E. Altamimi and M. Khan. 2017. The use of high tunnels to produce fruits and vegetable crop in North America. Agric. Sci., 8: 692-715. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2017.87052

Jat, R.J., S. Sing, H. Lal and L.R. Choudhary. 2012. Constraints faced by tomato growers in use of improved tomato production technology. J. Ext. Educ., 20: 159-163.

Kabir, K.H., M.E. Baksh, F.M.A. Rouf, M.A. Karim and A. Ahmed. 1996. Insecticide usage pattern on vegetables at farmers’ level of Jessore in Bangladesh. Bangl. J. Agric. Res., 20(2): 241-254.

Kang, Y., Y.C. Chang, H.S. Choi and M. Gu. 2013. Current and future status of protected cultivation techniques in Asia. Acta Hortic., 987: 33-40. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.987.3

Khan, B.M. and J. Khan. 2020. An economic analysis of tunnel farming in enhancing productivity of off-season vegetables in District Peshawar. Sarhad J. Agric. 36(1): 153-160. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.1.153.160

Mishra, R. and D. A. Kumar. 2012. Price behavior of major vegetables in hilly region of Nepal: An econometric analysis. SAARC J. Agric. 10(2):107-120.

Muhammad, S.A., A. Saghir, I. Ashraf, K.A. Awan and M.J. Alvi. 2014. An impact assessment of tunnel Technology transfer project in Punjab, Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J., 33(1): 33-37.

NBP, 2013. Off-season vegetable farming in tunnels. National Bank of Pakistan Report. pp. 1-15.

Pervaiz, U., A. Salam, D. Jan, A. Khan and M. Iqbal. 2018. Adoption constraints of improved technologies regarding tomato cultivation in District Mardan, KP. Sarhad J. Agric., 32(2): 428-434. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2018/34.2.428.434

Pervaiz, U., M. Iqbal and D. Jan. 2020. Analyzing the effectiveness of agricultural extension activities in District Muzaffarabad-AJK-Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 36(1): 101-109. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.1.101.109

Prajapati, B., 2007. Study on the off season vegetables farming and its impact on socio-economic development: A case study of Rasuwa District. 2010 by Micro-Enterprise Development Program (MEDEP). pp. 1-10.

Sadaf, S., S. Muhammad and T.E. Lodhi. 2005. Need for agricultural extension services for rural women in Tehsil Faisalabad. Pak. J. Agric. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 248-251.

Safdar, Z., 2005. Role of extension agent in the diffusion of onion and tomato crop. A case study of four selected villages of UC Sakhkot Malakand Agency. MSc. (Hons) thesis, Department of Agri. Ext. Edu. and Comm. The University of Agriculture Peshawar. pp. 15.

Sanaullah, 2018. An analysis of the adoption of improved farming practices of maize in Bajaur Agency. MSc. (Hons) thesis, Department of Agri. Ext. Edu. and Comm. The University of Agriculture Peshawar. pp. 28.

Sanaullah and U. Pervaiz. 2019. An effectiveness of extension trainings on boosting agriculture in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 35(3): 890-895. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2019/35.3.890.895

Sanaullah, U. Pervaiz, S. Ali, M. Fayaz and A. Khan. 2020. The Impact of improved farming practices on maize yield in Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 36(1): 348-358. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.1.348.358

Siddiqui, A.A. and Z. Mirani. 2012. Farmers’ Perception of agricultural extension regarding diffusion of agricultural technology. Pak. J. Agric. Eng. Vet. Sci., 20(2): 83-96.

Schreinmachers, P., M. Wu, M.N. Uddin, S. Ahmad and P. Hanson. 2016. Farmer training in off-season vegetables: Effects on income and pesticide use in Bangladesh. Food Policy, 61: 132-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.03.002

Tahir, A. and Z. Altaf. 2013. Determinants of income from vegetables problem production: A comparative study of normal and off-season vegetables in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Pak. J. Agric., 26(1): 24-31.

Ullah, R. and K. Nawab. 2019. Pesticidesuse in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province- Pakistan. Present Scenario. Int. J. Biol. Sci., 14(2): 197-208. https://doi.org/10.12692/ijb/14.2.197-208

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?