The Journal of Advances in Parasitology

Research Article

Patho-Surveillance and Pathology of Fascioliosis (Fasciola gigantica) in Black Bengal Goats

Kazi Mehetazul Islam*1, Md. Siddiqul Islam3, Shah Md. Abdur Rauf1, Alam Khan2, K. M. Mozaffor Hossain1, Moizur Rahman1

1Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Science, Faculty of Agriculture; 2Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi-6205; 3Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Science, Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet-3100, Bangladesh.

Abstract | The patho-surveillance with pathology of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats in Sylhet region of Bangladesh was investigated. Overall, 2000 goat livers were examined grossly to different upazilla slaughterhouses. Affected liver samples were collected randomly and histopathological study for hematoxylin and eosin staining. The overall prevalence of fascioliosis was 10.10%. Prevalence of fascioliosis was significantly higher in young goats (15.58 %) than in adult (9.59%) and female goats (13.10%) were more susceptible than male (7.10%). Highest prevalence (16.51 %) was recorded during rainy season and lowest in summer season (4.70%). Grossly, affected livers were enlarged with rounded edges and thickened capsule. In acute cases, numerous haemorrhagic spots were found on the parietal and visceral surfaces of the affected liver. In chronic form, liver was cirrhotic and reduced in size. The affected intra-hepatic bile ducts were protruded and engorged with flukes. Microscopically, migratory tracts were represented by the presence of haemorrhage, edema and infiltration of numerous eosinophils mixed with few lymphocytes. Fatty change, atrophy and necrosis of hepatocytes were recorded along with deposition of bile pigment in hepatic parenchyma and damage of portal tract area. The wall of bile ducts was thickened due to fibrosis and lining epithelia were hyperplastic. Cross sections of adult and immature flukes were found within the lumen of the thickened bile ducts and hepatic parenchyma respectively. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of fascioliasis in Black Bengal goats were adopted suitable control strategies against the disease and meat inspection at slaughterhouses.

Keywords | Fasciola gigantica, Pathology, Patho-surveillance, Goats, Sylhet, Bangladesh

Editor | Muhammad Imran Rashid, Department of Parasitology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan.

Received | December 01, 2015; Revised | January 22, 2016; Accepted | January 25, 2016; Published | April 06, 2016

*Correspondence | Kazi Mehetazul Islam, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh; E-mail: [email protected]

Citation | Islam KM, Islam MS, Rauf SMA, Khan A, Hossain KMM, Rahman M (2016). Patho-surveillance and pathology of fascioliosis (Fasciola gigantica) in black Bengal goats. J. Adv. Parasitol. 3(2): 49-55

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.14737/journal.jap/2016/3.2.49.55

ISSN | 2311-4096

Copyright © 2016 Islam et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

INTRODUCTION

The Black Bengal goats are the second most important livestock in Bangladesh which contribute in poverty alleviation and supply animal protein of high caloric value in the form of milk and meat. Parasitic disease especially F. gigantica infection in ruminants causes enormous economic losses in livestock production in terms of costs of anthelmintics, reduction in milk and meat production, loss of fertility and reduced draught power. The disease also has public health significance, causing human fascioliosis (Vassilev and Jooste, 1991; Lebbie et al., 1994). Fecal sample examination is a usual tool to diagnose and to investigate prevalence and incidence of fascioliosis which is based on identification and counting of eggs. Information regarding epidemiology of fascioliosis on the basis of liver pathology is almost nil though liver damage is a key factor of heath status, productive and reproductive performance and body immunity and mortality of the animal (Ngategize et al., 1993; Nonga et al., 2009). Depending on climatic conditions, seasonal occurrence of fascioliosis varies from country to country, even among different regions within a country. The disease usually occurs continuously if suitable temperature (above 10°C) and moisture are available. High incidence and clinical disease with high mortality are reported to occur in wet seasons (Singh & Singh, 2009; Bansel et al., 2013). Chronically infected domestic ruminants are usually responsible for the spread of the disease through contaminating the pastures with liver fluke eggs which is especially seen in areas having favorable climatic conditions and suitable snails. Many research works were carried out on different aspects of fascioliosis in buffaloes (Alam et al., 1994), cattle (Chowdhury et al., 1994), goats (Hossain et al., 1998) and sheep (Alim et al., 2000) in Bangladesh. However, there is a few or limited studies on epidemiology and pathology of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats in Bangladesh. Taken together above-mentioned points a thorough investigation on the patho-surveillance of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats of Bangladesh is required. Therefore, the present study was carried out to investigate the prevalence of F. gigantica infection in Black Bengal goats based on liver pathology and to find out the influence of age, sex and seasons on its prevalence in Sylhet region of Bangladesh.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area and Experimental Animal

This study was conducted in Sylhet region of Bangladesh. Sylhet region is located in the North-East part of Bangladesh between 24°30’ North latitude and 91°40’ East longitudes. The division has an area of 3490.40 square kilometers. More than three quarter of the division consists of mostly tea garden, hilly, water logged and low lying areas. The average maximum and minimum temperatures are 23oC and 7oC respectively. The annual average rainfall is 3334 mm and humidity is 80%. Laboratory analysis of collected liver samples were carried out at the Department of Parasitology, Anatomy and Histology under the Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Science, Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet, Bangladesh for the period from July 2012 to June 2013. Different areas of Sylhet region were selected on the basis of irrigated agro-ecological zones such as Sylhet Sadar, Balaganj, Beanibazar, Biswanath and Jaintapur upazilla. All the studied animals were Black Bengal goats, which were purchased by the butchers from different upazilla of Sylhet region, reared in rural husbandry practices. Both male and female Black Bengal goats of two different age groups such as young (<1.5 years) and adult (≥ 1.5 years) were considered.

Examination of Liver and Collection of Samples

During the study year, a number of 2000 Black Bengal goats at slaughterhouses in five different upazilla of Sylhet region were examined to record the prevalence of the disease in a systematic survey. Post-mortem examinations of slaughtered Black Bengal goats were carried out and livers with gall bladder were closely examined at the laboratory for gross pathology and for the collection of flukes following the procedure of Ross (1967). F. gigantica was identified on the basis of morphology Soulsby (1986).

Table 1: Prevalence of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats at different sampling locations

|

Sampling location |

No. of animals examined |

No. of positive cases |

Prevalence (%) |

|

Sylhet Sadar |

400 |

33 |

8.25 |

|

Balaganj |

400 |

40 |

10.00 |

|

Beanibazar |

400 |

43 |

10.75 |

|

Biswanath |

400 |

48 |

12.00 |

|

Jaintapur |

400 |

38 |

9.50 |

|

Total |

2000 |

202 |

10.10 ± 0.63§ |

§ ± standard deviation

Laboratory Procedure

During collection of parasite, affected Black Bengal goat livers with gall bladders were subjected to thorough investigation and those showing evidence of infection were collected and processed for histopathology. Formalin fixed liver tissues were processed, embedded in paraffin wax, cut in appropriate thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as per standard methods described by Luna (1968).

Statistical Analysis

Variations on the prevalence of fascioliosis in different age groups, sex and seasons were analyzed by logistic regression using statistical software SPSS (Version 15.2) and Microsoft Excel 2007. Relationship of different variables with the infection was observed by regression analysis.

Table 2: Age-wise prevalence of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats at different sampling locations

|

Sampling location |

Young (age <1.5 years ) |

Adult (age ≥1.5 years ) |

||||

|

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

|

|

Sylhet Sadar |

34 |

04 |

11.77 |

366 |

29 |

7.92 |

|

Balaganj |

28 |

05 |

17.86 |

372 |

35 |

9.41 |

|

Beanibazar |

23 |

04 |

17.39 |

377 |

39 |

10.35 |

|

Biswanath |

49 |

09 |

18.37 |

351 |

39 |

11.11 |

|

Jaintapur |

40 |

05 |

12.50 |

360 |

33 |

9.17 |

|

Total |

174 |

27 |

§15.58 ±1.42** |

1826 |

175 |

§9.59±0.54** |

§ ± standard deviation; p value is calculated between age groups (** p<0.004)

Table 3: Sex-wise prevalence of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats at different sampling locations

|

Sampling location |

Male |

Female |

||||

|

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

|

|

Sylhet Sadar |

200 |

12 |

6.00 |

200 |

21 |

10.50 |

|

Balaganj |

200 |

13 |

6.50 |

200 |

27 |

13.50 |

|

Beanibazar |

200 |

15 |

7.50 |

200 |

28 |

14.00 |

|

Biswanath |

200 |

18 |

9.00 |

200 |

30 |

15.00 |

|

Jaintapur |

200 |

13 |

6.50 |

200 |

25 |

12.50 |

|

Total |

1000 |

71 |

§7.10±.53*** |

1000 |

131 |

§13.10±.77*** |

§ ± standard deviation; p value is calculated between male and female (*** p<0.001)

Where specified, the data were analysed for statistical significance using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Overall Prevalence

In the present study, a total of 2000 slaughtered Black Bengal goats were examined of which 202 were found positive for F. gigantica and the overall prevalence was recorded as 10.10%. The highest prevalence was found at Biswanath upazilla (12.00%) followed by Beanibazar (10.75%), Balaganj (10.00%), Jaintapur (9.50%) and Sylhet Sadar (8.25%) (Table 1). The highest prevalence of fascioliosis was 12.00% in Biswanath and the lowest was 8.25% in Sylhet Sadar upazilla. The overall prevalence and prevalence of five different upazilla was correlated with the findings of Selim et al. (1997), Olupinyo & Ajanusi, (2005), Islam & Taimur, (2008), Mohsen et al. (2008), Mellau et al. (2010), Henok & Mekonnen, (2011), Abdulhakim & Addis (2012), Kadir et al. (2012) and Jean-Richard et al. (2014) who reported the prevalence as 8.7%, 8%, 14.28%, 13.7%, 18.5%, 8.8%, 13.9%, 14% and 12%, respectively on the basis of liver examination. The geo-climatic conditions together with the water logged & low lying areas in Sylhet region of Bangladesh and most of the animals graze on the low land where are highly favorable for the development and multiplication of Fasciola species and their intermediate hosts (snails).

Influence of Age, Sex and Seasons on the Prevalence of Fascioliosis (Fasciola gigantica) in Black Bengal Goats

The prevalence was significantly higher in young Black Bengal goats aged <1.5 years (15.58%) than in adults aged ≥1.5 years (9.59%) (Table 2). Young goats were 1.63 times more susceptible to F. gigantica infection than adults. Similar observations were reported by Tasawar et al. (2007) and Keyyu et al. (2003). Higher prevalence in young goats might be due to less immune protection as immunity plays a great role in the establishment of parasites in the host body. When animals cross one year of age the major part of their parasitic infection is eliminated by so called self cure phenomenon and/or high acquired immunity which increases with age. Winkler, (1982) reported that host may recover from parasitic infection with increasing age and hence become resistant. Similar observations were reported by Tasawar et al. (2007) and Keyyu et al. (2003).

The overall prevalence of fascioliosis was higher in female (13.10%) than in male (7.10%) (Table 3). Females were 1.85 times more susceptible to F. gigantica infection than males. Moreover, the prevalence of fascioliosis was higher in females Black Bengal goats than males in each upazilla of Sylhet region, Bangladesh (Table 3). These findings are in agreement with Fatima et al. (2008) who reported higher prevalence in female goats. Physiological peculiarities of female animals which usually constitute stress factors like calving and lactation reduced their immunity to infections.

Table 4: Season-wise prevalence of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats at different sampling locations

|

Sampling location |

Rainy |

Winter |

Summer |

||||||

|

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

No. examined |

No. positive |

Prevalence (%) |

|

|

Sylhet Sadar |

140 |

19 |

13.57 |

147 |

10 |

6.80 |

113 |

04 |

3.54 |

|

Balaganj |

149 |

24 |

16.11 |

148 |

11 |

7.43 |

103 |

05 |

4.85 |

|

Beanibazar |

149 |

27 |

18.12 |

142 |

10 |

7.04 |

109 |

06 |

5.50 |

|

Biswanath |

138 |

29 |

21.01 |

144 |

12 |

8.33 |

118 |

07 |

5.93 |

|

Jaintapur |

189 |

26 |

13.76 |

129 |

09 |

6.98 |

82 |

03 |

3.66 |

|

Total |

765 |

125 |

§16.51±1.40***a |

710 |

52 |

§7.32±0.27 ***b |

525 |

25 |

§4.70±0.48 ***b |

§ ± standard deviation; In a column among seasons with same alphabet do not differ significantly as per DMRT; Data were calculated at 99.99% level of significance and a p value <0.001 was considered significant

Figure 1: Gross pathology of Black Bengal goat liver in acute (A & B) and chronic (C & D) fascioliosis

(A-B) Swollen and enlarged liver characterized by rounded edges (arrow), congestion and fibrin deposition (arrow) on visceral surface; A) distended gallbladder (arrow), swollen and congested hepatic lymph node (arrow), adult fluke attached on parietal surface; B) (C-D) Atrophy of liver in chronic fascioliosis, irregular and granular (arrow) visceral surface; C) congested bile duct (arrow), fibrosed parietal surface; D) adult fluke in bile duct (arrow)

Females are usually weak and malnourished and consequently are more susceptible to infections besides some other reasons Blood (2000).

The seasonal influence of F. gigantica infection is shown in Table 4. The highest prevalence of F. gigantica was recorded during rainy season (16.51%) followed by winter (7.32%) and summer (4.70%). The highest and lowest prevalence of fascioliosis in Black Bengal goats were 21.01% and 13.57% in rainy season; 8.33% and 6.80% in winter; 5.93% and 3.54% in summer at Biswanath and Sylhet Sadar upazilla respectively. Similarly significant differences were observed in each upazilla. Our findings are in agreement with the findings of Jithendran and Bhat, (1999), Tamloorkar et al. (2002). Climatic conditions, particularly rainfall, were frequently associated with differences in the prevalence of fascioliosis because this was suitable for intermediate hosts like snails to reproduce and to survive longer under moist conditions (Ahmed et al., 2007). Moreover, Bangladesh has a rainy season for four months, which facilitates parasitic survival in such an environment.

Pathological Changes in Black Bengal Goat Liver Affected with Fascioliosis (Fasciola Gigantica)

Visible mucous membranes of Fasciola gigantica infected Black Bengal goats were pale to a large extent and ‘bottle jaw’ syndrome was occasionally found. Gross pathological changes are shown in Figure 1. Gross pathological changes of affected livers in acute fascioliosis were characterized by slightly swollen and enlarged livers with round edges and thickened capsule with numerous hemorrhagic spots on the parietal and visceral surfaces (Figure 1A, 1B). Affected livers were soft in consistency. Adult liver flukes were attached with the hepatic parenchyma. Hepatic lymphnodes were hemorrhagic, congested and swollen (Figure 1A). In chronic form, affected livers were cirrhotic and reduced in size with irregular and granular surfaces (Figure 1C, 1D). The colour of the livers became pale; the capsule was thick, opaque, rough and was closely adhered with parenchyma. The parietal surface of the liver was covered with whitish colour fibrous connective tissue and the parenchyma was somewhat tough to cut due to the presence of fibrous connective tissue and healing of migratory tracts caused by the immature flukes. The affected intra-hepatic bile ducts were protruded and were engorged with pre-adults and adult flukes. In majority cases, the gall bladder was highly distended with bile. The bile ducts were tough to cut due to proliferation of fibrous connective tissue. Adult and immature F. gigantica worms were found within the bile duct and portal vein of the Black Bengal goat liver. The affected bile ducts were moderately distended and contained both pre-adult and few adult flukes mixed with dirty bile and tissue debris. Our gross pathological findings in Black Bengal goat livers are similar to the observations of Masuduzzaman et al. (1999), Ahmedullah et al. (2007), Rahman et al. (2007), Okaiyeto et al. (2012), Affroze et al. (2013) in cattle, Alim et al. (2008) in buffalo, Adama et al. (2011) in sheep and Masuduzzaman et al. (1999) in deer.

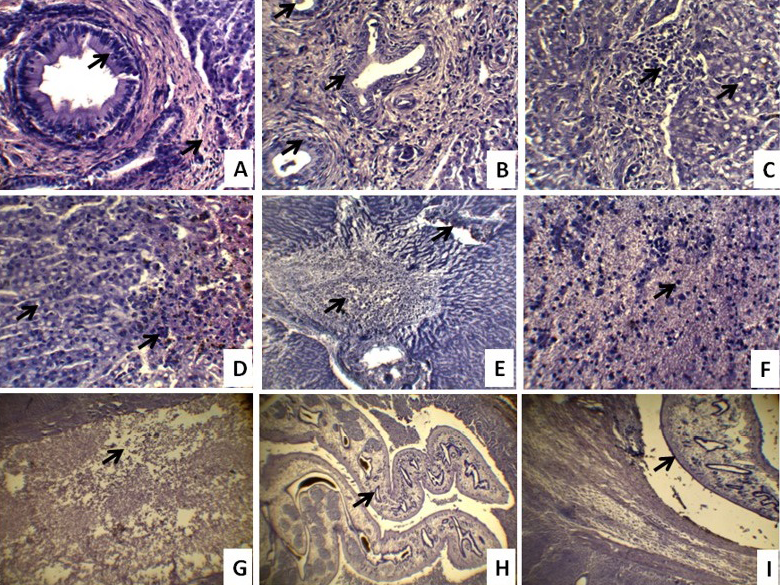

Histopathological changes in affected Black Bengal goat livers are depicted in Figure 2. The wall of bile ducts was thickened due to fibrous tissue proliferation and the lining epithelium showed hyperplastic changes (Figure 2A, 2B). In advanced stages, these hyperplastic changes in some of the larger bile ducts appeared as gland like structure and the dilated ducts produced pressure atrophy, necrosis, and fatty changes of surrounding hepatocytes. There were fatty changes and atrophy of hepatocytes and infiltration of inflammatory cells in hepatic parenchyma (Figure 2C). There was hemorrhage and deposition of bile pigment in the tissue spaces of hepatic parenchyma (Figure 2D). There were coagulation necrosis, loss of hepatocytes and destruction of hepatic portal area (Figure 2E). Coagulation necrosis was characterized by pyknotic nuclei of hepatocytes and more acidophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2F). Eosinophilic infiltration with few lymphocytes was more common in the migratory tract within the hepatic parenchyma (Figure 2G). The cross sections of adult and immature F. gigantica were found in the lumen of the thickened bile ducts and hepatic parenchyma (Figure 2H, 2I). No calcification observed in the wall of the bile ducts in chronic fascioliosis of Black Bengal goat. Similar observations were made by Masuduzzaman et al. (2005) and Okaiyeto et al. (2012). In chronic fascioliosis, fibrosis of portal area and thickening of the bile duct without calcification were observed. These observations are in agreement with chronic fascioliosis of

A) Bile duct hyperplasia & fibrosis (arrow), thickening of bile duct, loss of hepatocytes and atrophy of the hepatic parenchyma; B) Excess bile duct proliferation and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the hepatic parenchyma; C) Fatty change and atrophy of hepatocytes and infiltration of inflammatory cells in hepatic parenchyma; D) Fatty change, hemorrhage and deposition of bile pigment in the tissue spaces of hepatic parenchyma; E) Coagulation necrosis, loss of hepatocytes, infiltration of inflammatory cells, destruction of portal area and atrophy of the hepatic parenchyma; F) Pyknotic nuclei and more acidophilic cytoplasm of hepatocytes indicating coagulation necrosis; G) Migratory tract within the hepatic parenchyma; H) Cross section of adult F. gigantica within the gallbladder, excessive proliferation of glands and thickening of the wall of bile duct; I) The cross section of adult and immature Fasciola worm within the hepatic parenchyma, bile duct due to loss of hepatocytes. The histopathological pictures are representative of sections derived from five goats in each case (H&E 10x, 40x)

sheep and pig where no calcification in the wall of bile ducts was recorded (Masuduzzaman et al., 2005; Chiezey et al., 2013). However, calcification was seen in cattle liver (Badr and Eman, 2009; Okaiyeto et al., 2012) which might be due to species variation or stage of infection.

CONCLUSION

The geo-climatic conditions along with the water logged and low lying areas in Sylhet region of Bangladesh are highly favorable for the development and multiplication of F. giagntica and their intermediate hosts (snails). In this study, we showed the patho-surveillance, gross and histopathological changes in F. gigantica affected Black Bengal goat livers which provides valuable in insight towards better understanding of epidemiology and pathogenesis of the disease in Black Bengal goats to adopt suitable control strategies against the disease. Our study results may also have significant values in terms of meat inspection at slaughterhouses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study is a part of my PhD. I am very much thankful to the department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi-6205, for logistic support and the authority of Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet for granting me study leave to complete the study. Authors greatly acknowledge the technical assistance provided by the laboratory technicians of both the laboratories of Sylhet Agricultural University and University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Author contribution

Kazi Mehetazul Islam has examined the liver from slaughterhouse cattle and written the whole article. Shah Md. Abdur Rauf, Md. Siddiqul Islam and Moizur Rahman for his kind, scholastic guidance and valuable advice throughout the research activities and preparation of the manuscript. Khandoker Mohammad Mozzafor Hossain and Alam Khan helped in laboratory examination of the collected samples.

REFERENCES