Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences

Prevalence and Ecology of Zoonotic Methicillin Resistant S. aureus and its Relation to Biofilm Formation

Sahar Abdel Aleem Abdel Aziz1, Manar Bahaa El Din Mohamed1*, Ismail A Radwan2

1Department of Hygiene, Zoonoses and Epidemiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni–Suef University, 62511Beni–Suef, Egypt; 2Department of Bacteriology, Mycology and Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni–Suef University, 62511Beni–Suef, Egypt.

Abstract | The high zoonotic importance of Staphylococcus aureus and the increasing rates of isolation of methicillin resistant traits from both clinical and subclinical cases pose a major threat to human health and animal industry. The aim of this study was to monitor methicillin–resistant isolates of S. aureus recovered from milk, human and environmental samples in a small holder dairy unit, detection of their antibiotic resistance and their relation to biofilm formation. Seventy-five milk samples besides 150 different environmental samples including (bulk milk tank swabs, water trough swabs, feeding manager swabs, milk machine swabs, and bedding) and 50 nasal and attendants’ hand swabs from animal attendants were collected using stratified random sampling technique. Samples were aseptically cultured for isolation of S. aureus that was confirmed using molecular assays. Antibiotic sensitivity pattern and biofilm formation using disc diffusion and Congo red method, respectively were detected. Resistant isolates were screened for Mec A and Ica A genes. The highest isolation percentage (64.0%) was obtained from manager followed by milk machine swabs (60.0%). All strains showed complete resistance to cefoxitin and ampicillin (100.0% each) and varying degrees of resistance to other used antibiotics. Mec A gene was detected in 5 out of 6 examined isolates meanwhile Ica A gene was detected in all the tested isolates. It can be concluded that the environment considered the link between animal and human infections through poor standards of hygiene and a possible cross relation between antibiotic resistance particularly to methicillin and biofilm formation was also observed.

Keywords | Antibiotic Resistance, Biofilm, Cow’s Environment, MRSA, S. aureus

Received | February 25, 2019; Accepted | March 30, 2019; Published | May 30, 2019

*Correspondence | Manar Bahaa El Din Mohamed, Department of Hygiene, Zoonoses and Epidemiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni–Suef University, 62511, Beni–Suef, Egypt; Email: [email protected]

Citation | Sahar A Abdel Aziz, Manar B Mohamed, Radwan IA (2019). Prevalence and ecology of zoonotic methicillin resistant s. aureus and its relation to biofilm formation. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 7(7): 609-616.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.aavs/2019/7.7.609.616

ISSN (Online) | 2307-8316; ISSN (Print) | 2309-3331

Copyright © 2019 Aziz et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is an important bacterial pathogen that causes a variety of diseases in animals and humans ranging from only skin infections to life threatening bacteraemia (Incani et al., 2013). Milk and its derivatives consider a potential source of infection to human society due to the ability of milk to act as a vehicle to such vicious disease agent (Iqbal et al., 2016).

Over the last decade’s methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolated from both humans and animals have been reported worldwide (Naimi et al., 2001; Voss et al., 2005). Misuse of antibiotics in the treatment of staphylococcal infections had led to one important complication; the emergence and maintenance of antibiotic resistant traits among pathogenic S. aureus strains (Stastkova et al., 2009). Noteworthy that multidrug resistance (MDR) among S. aureus strains has become very common which poses a high risk to both human and veterinary medicine (Khan et al., 2007).

Farm animals infected or carrying MRSA strains can easily be involved in the spread of the pathogen not only to the farm personnel but also to raw food materials intended for further processing (Stastkova et al., 2009). Therefore detection of the resistance pattern is a supportive tool to antibiotic treatment guidelines (Beema and Atindra, 2011).

S. aureus can survive on inanimate objects for prolonged time therefore the environment plays uncontroversial role in the spreading MRSA between animal and human populations (Davis et al., 2012). Milk and dairy products contaminated with antibiotic resistant bacteria including MRSA present a major threat to public health as a result of continuous circulation of resistant pathogens in the environment (Gwida and El-Gohary, 2015).

Biofilm is one feature of some bacteria that protects the microorganism from host defenses and impedes delivery of antibiotics (Gurjala et al., 2011). Virtually it was found that multiple antibiotic resistances increased in MRSA having the ability to form a biofilm causing failure of treatment, chronic and recurrent infections (Diemond–Hernández et al., 2010: Pozzi et al., 2012; Neopane et al., 2018).

The objectives of this study was to monitor the prevalence of methicillin–resistant strains of S. aureus recovered from animal, human and environmental samples in a small dairy unit, and to assess the relation between biofilm formation and their resistance pattern to different antibiotics in such strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area and Design

This study was carried out in a private dairy farm located in Beni-Suef district (coordinates: 29E04’N31E05’E), Egypt during the period from June 2017 to April 2018. The farm consisted of 135 Friesian cows of different production stages. Cows were housed in a partially sheltered yards in 9 groups (n=15) according to their production, with earthy floor, each group was provided with a common water trough and a common feeding trough. Cows were milked twice/ day in abreast parlor prepared with 12 milking units. Eventually milk from cows was collected in a bulk tank to be ready for transportation. The hygienic status that prevailed in the farm based on observation and a questionnaire was poor. Seventy-five milk samples besides 150 different environmental samples including (bulk milk tank swabs, water trough swabs, feeding manager swabs, milk machine swabs, and bedding) and 50 nasal and attendants’ hand swabs from animal attendants were collected using stratified random sampling technique. Samples were aseptically cultured for isolation of S. aureus and the identified isolates were tested for antibiotic sensitivity against seven different antibiotics (ampicillin, amoxicillin clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, cefepime, oxytetracycline, enroflxacin and kanamycin) using disc diffusion method (CLSI, 2017). Resistant bacteria were tested for biofilm formation using Cogo Red Agar method then they were screened for MRSA resistance and biofilm formation genes using molecular techniques.

Sample Collection

A total number of 75 milk samples, (approximately 10 mL) were collected from different animals that did not show any signs of clinical mastitis. Sampling collection were done randomly twice/ month throughout the study period. All milk samples were gathered according to National Mastitis Council (1990) and they were kept in ice box to be sent with minimal delay to the laboratory of Hygiene, Zoonoses and epidemiology in the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni–Suef University. One hundred and fifty environmental samples including bulk milk tank swabs, water trough swabs, feeding manager swabs, milk machine swabs, and bedding. Beside, fifty human samples including attendants’ hand swabs (n= 25) and nasal swabs (n= 25) were collected from the dairy farm workers and attendants. All attendants were men; their ages were ranged from 20–40-year-old, and apparently healthy.

Isolation and Identification of S. Aureus

One loopful from each milk sample was inoculated on Baird Parker agar plates (BRA, Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) supplemented with egg yolk tellurite and incubated at 370 C for 24–48 hrs. Typical black colonies with opaque halo were collected and streaked on tryptic soya agar plates incubated at 370 C for 24 hrs, the purified colonies were preserved on tryptic soya agar slopes at 40 C for further identification.

Whereas All the swab samples were pre–enriched on tryptic soy broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) at 370 C for 18–24 hrs then a loopful from each tube showing turbidity was cultivated on the surface of Baird Parker agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 370 C for 24–48hrs. The purified isolates were identified on the basis of Gram staining, oxidase, catalase and coagulase tests (Biolife, Milan, Italy) according to Quinn et al. (2002). Further identification of the isolates was applied by amplification of S. aureus specific Nuc gene.

Phenotypic Screening of Biofilm Formation

Biofilm formation was determined qualitatively using Congo red agar assay (CRA) (Osman et al., 2015), depending on the characteristic morphology of S. aureus biofilm formation on CRA. Colonies were cultured on CRA plates consisting of; 37 g/L of Brain Heart Infusion agar (BHI, Merck), 0.8 g/L of Congo red dye (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 50 g/L of sucrose (Merck). Isolates were inoculated on CRA plates and incubated aerobically at 370 C for 24 hrs and then plates were kept at room temperature for 48 hrs.

Table 1: Sequences of target genes, amplicon sizes and cycling conditions specific for S. aureus

| Target gene | Primer sequences | Amplified segment (bp) |

Primary denaturation |

Amplification (35 cycles) |

Final extension |

References | ||

| Secondary denaturation | Annealing | Extension | ||||||

| Nuc |

ATATGTATGGC AATCGTTTCAAT |

395 |

94˚C 5 min. |

94˚C 30 sec. |

55˚C 45 sec. |

72˚C 45 sec. |

72˚C 10 min. |

|

GTAAATGCAC TTGCTTCAGGAC |

||||||||

| Mec A | GTA GAA ATG ACT GAA CGT CCG ATA A |

310 |

94˚C 5 min. |

94˚C 30 sec. |

50˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 7 min. |

|

CCA ATT CC A CAT TGT TTC GGT CTA A |

||||||||

| Ica A | CCT AAC TAA CGA AAG GTA G | 1315 |

94˚C 5 min. |

94˚C 30 sec. |

49˚C 45 sec. |

72˚C 1.2 min. |

72˚C 12 min. |

|

The results of biofilm formation were interpreted according to colonial morphology using a four–color reference scales varying from red to black. Black colonies were considered to be biofilm–producers, while almost–black colonies were considered weak biofilm producers. Red and purple colonies were considered non–biofilm producers (Lira et al., 2016).

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

The antimicrobial sensitivity test was done by disk diffusion method according to CLSI (2017) using seven antibiotics (ampicillin 10 μg, amoxicillin clavulanic acid 25 μg, cefoxitin 30 μg, cefepime 25 μg, oxytetracycline 30 μg, enrofloxacin 10 μg and kanamycin 3 μg) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK).

Molecular Analysis of Mrsa and Biofilm Genes

Six resistant strains of S. aureus to cefoxitin were randomly selected and submitted for detection of Mec A gene that is implicated in methicillin resistance and Ica A genes required for synthesis of PIA for biofilm formation (Boye et al., 2007) by molecular analysis, which was applied in biotechnology center in the animal health research institute according to Sambrook and Russel (1989). The primer sequencing and cycling conditions for the target genes were mentioned in Table 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mastitis and in particular subclinical one caused by S. aureus is a primary and the most lethal agent affecting our cattle. Increasing concern about the presence of such contagious zoonotic pathogen that cause several pathological conditions to humans and spread between cows during the milking time through contaminated environment and attendants hands (Artursson et al., 2016). Such circumstance resembles a circle where pathogens, susceptible animals, human, and the environment play a specific role in magnification of the problem.

Table 2: Prevalence of S. aureus isolated from different examined samples throughout the study period

|

S. aureus prevalence

Samples/ Swabs |

Examined samples (No.) |

Positive samples (No.) (%) |

| Cows: | ||

| Milk sample | 75 | 18 24.0 |

|

Humans: |

||

| Nasal swab | 25 | 10 40.0 |

| Attendant's hand | 25 | 7 28.0 |

| Cows' environment: | ||

| Water sample | 25 | 0 0.0 |

| Water trough | 25 | 0 0.0 |

|

Feeding manager |

25 | 16 64.0 |

| Bedding | 25 | 0 0.0 |

| Milk tank | 25 | 0 0.0 |

| Milk machine | 25 | 15 60.0 |

| Total | 275 |

66 24.0 |

S. aureus was isolated from 66 (24.0%) of 275 samples based on cultural and biochemical properties as shown in Table 2, moreover the highest bacterial isolation rate was obtained from feeding manager (environmental sample) followed by swabs from milk machine, nasal swabs, attendants’ hand swab (human samples) and milk sample (animal samples) (64.0, 60.0, 40.0, 28.0 and 24.0%, respectively), while no isolation was obtained from bedding, milk tank swabs, water sample or water trough swabs (0.0%). In the

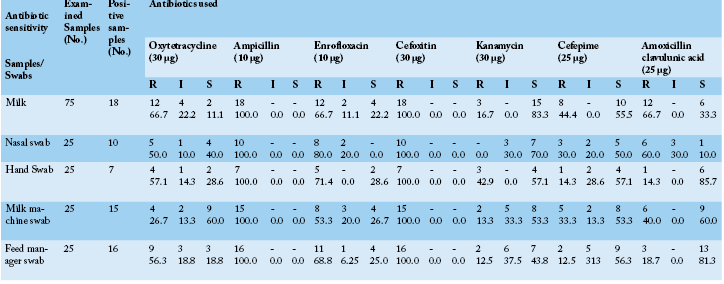

Table 3: S. aureus sensitivity isolated from cows, attendants and their environment against seven antibiotics using disc diffusion method in- vitro

*S: Sensitive, I: Intermediate, R: Resistant

Table 4: Prevalence and categorization of biofilm forming isolates of S. aureus using CRA obtain from cows, humans and their environment

|

Biofilm formation

Samples / Swabs |

Samples | Biofilm Category | ||||

|

Examined

|

Positive |

Negative No. % |

Weak No. % |

Moderate No. % |

Strong No. % |

|

|

Animal samples Milk |

75 |

18 |

4 22.2 |

9 50.0 |

5 27.8 |

0 0.0 |

|

Human samples (hand & nasal swabs) |

50 |

17 |

4 23.5 |

8 47.1 |

2 11.8 |

3 17.6 |

|

Environmental Samples (milk machine, manager) |

50 |

31 |

16 51.6 |

8 25.8 |

5 16.1 |

2 6.5 |

| Total | 175 | 66 | 24 36.4 | 25 37.9 | 12 18.2 |

5 7.6 |

Table 5: Correlation between antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation in S. aureus isolates

|

Biofilm formation

Antibiotic |

No. of resistant isolates | |||||

|

Biofilm former No. % |

Non–biofilm former No. % |

|||||

| Amoxicillin clavulanic acid | 28 | 10 | 35.7 | 18 | 64.3 | |

| Cefepime | 19 | 5 | 26.3 | 14 | 73.7 | |

| Kanamycin | 10 | 3 | 30.0 | 7 | 70.0 | |

|

Cefoxitin |

66 | 42 | 63.6 | 24 | 36.4 | |

| Enrofloxacin | 44 | 20 | 45.5 | 24 | 54.5 | |

| Ampicillin | 66 | 42 | 63.6 | 24 | 36.4 | |

| Oxytetracycline | 34 | 15 | 44.1 | 19 |

55.8 |

|

present study frequent distribution of S. aureus isolated from different samples revealed that most of the isolates were obtained from the animals’ environment in particular milk machine and feeding manager swabs that spot light on the importance of regular cleaning and disinfection inside the farm and this could be attributed to the general standards of hygiene in the farm under study was poor and not sufficient enough to eliminate the risk of infection from the environment that could be the reservoir for both animals and humans in contact. Zakary et al. (2011) concluded that high incidence of S. aureus is indicative of poor hygienic measures during production and handling. Attendants’ hands are considered as a source of contamination with S. aureus in dairy farms (Roberson et al., 1998; Zadoks et al., 2002; Olivindo et al., 2009; Matyi et al., 2013). The results obtained in this study were nearly similar to those reported by Hamid et al. (2017) and Unnerstad et al. (2009).

Concerning the results of antibiotic sensitivity profile (Table 3) of the obtained strains of S. aureus were remarkably resistant to two or more of the tested antibiotics (multi-drug resistance) moreover they all were completely resistant to ampicillin and cefoxitin (100.0%), also all samples showed a higher degree of resistance to enrofloxacin mainly the strains recovered from nasal swabs followed by hand swabs, feed manager swabs milk samples and milk machine swab (80.0, 71.4, 68.8, 66.7 and 53.3%, respectively). Variable degrees of resistance were recorded against the other tested antibiotics. On the other strains recovered from milk samples and nasal swabs exhibited high sensitivity mainly to kanamycin (83.3 and 70.0%, respectively) while hand swabs and feed manager swabs exhibited nearly similar sensitivity to cefepime (57.1 and 56.3%, respectively). Antibiotic sensitivity testing had revealed that most of recovered traits of S. aureus showed multidrug resistance in particular to cefoxitin and ampicillin (100.0%). The obvious pattern of multidrug resistance of the studied strains of S. aureus from animals, humans or environment spot light on a leading problem of possibility cross antibiotic resistance between the three sources although environmental isolates exhibited to some extent lesser degree of resistance compared to animal and human strains and this may be due to the less use of antibiotics to control them as well less use of disinfectants in this farm. Arenas et al. (2017) revealed that the livestock producers could be a source of exposure to multidrug resistant S. aureus strains as a result of abuse of antibiotic treatment of animals and unhygienic livestock practices. These results were to some extent in harmony with De Oliveira et al. (2000) and Guerin et al. (2003). On the contrary to the findings in this study Begum et al. (2007) recorded that S. aureus was 82.86% and 37.14% resistant to penicillin–G and amoxicillin.

Referring to the prevalence of biofilm forming strains of S. aureus using CRA as shown in Table 4 it was found that out of 66 strain of S. aureus 25 (37.9%) were capable of forming weak biofilm whereas 5 (7.6%) and 12 (18.2%) exhibited strong and medium biofilm formation capacity respectively. Meanwhile 24 (36.4%) did not show any biofilm formation. More specifically it was clear that the half of animal samples (milk samples) (50.0%) exhibited weak biofilm capacity, while 47.1% of human samples (nasal and hand swabs) were weak biofilm formers. Concerning the environmental samples (milk machine and feed manager swabs) the majority (51.6%) showed no biofilm formation. The result of biofilm formation pattern of the obtained isolates revealed that 37.9% of all isolates were weak biofilm formers, 18.2% were moderate biofilm forming and 7.6% were strong biofilm formers while 36.4% were non biofilm formers. Similar results were recorded by Eyoh et al. (2014) who identified biofilm production in 35.6% of S. aureus isolates. And Chibueze et al. (2017) who reported that 48.2% of the isolates have the potential to form biofilm and 5.4% were strong biofilm producers while 8.9% were moderate producers, 33.9% were weak producers and 51.8% were non biofilm producers. The implications of biofilm forming isolates of S. aureus in infection in hospitals environment and hospital personnel act as a steady reservoir that negatively impact the patient health due to biofilm formation inversely influence the antimicrobial therapy (Fatima et al., 2011).

Regarding the relation between antibiotic resistance of the recovered strains and their ability to form biofilm (Table 5) there was an obvious relation between their ability for biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance where 42 (63.6%) out of 66 resistant strain to cefoxitin and ampiciilin were able to form biofilm, followed by 20 (45.5%) of resistant strains to enrofloxacin were biofilm formers and 15 (44.1%) of those resistant to oxytetracycline were able to produce biofilm. On the other hand recovered strains that showed the least resistance to kanamycin and cefepime had the least ability to produce biofilm (30.0 and 26.3%, respectively), in other words it was clear that there is a positive relation between antibiotic resistance and the ability for biofilm formation in the same strains of S. aureus. Concerning the correlation between biofilm formation and antibiotic sensitivity pattern appositive correlation was noticed between antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation similar results obtained by Eyoh et al. (2014). Also Fitzpatrick et al. (2005) found more MDR strains in biofilm producers than in non–biofilm producers. Biofilm formation in MDR S. aureus could be attributed to presence of extracellular polymeric substance that constitute this matrix serving as a diffusional barrier for antibiotics, thus influencing either the rate of transportation of the molecule to the biofilm or the reaction of the antibiotic with the matrix material (Corrigan et al., 2007).

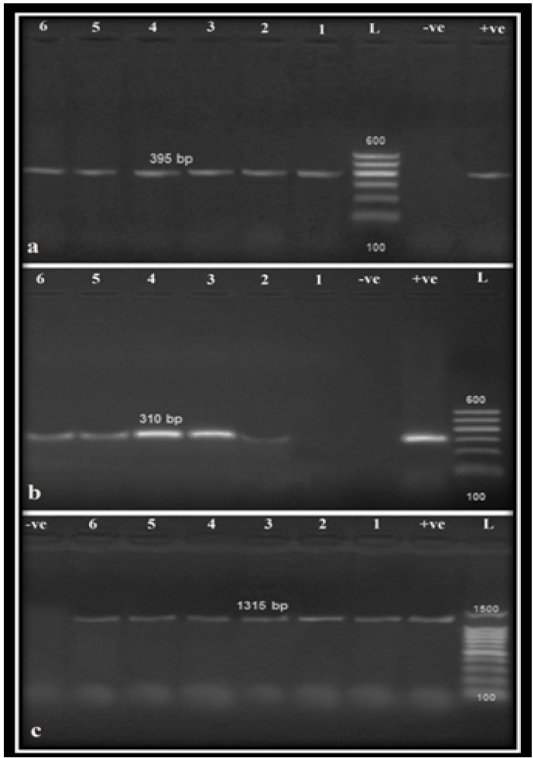

Results of polymerase chain reaction for detection of Nuc gene, MRSA gene (Mec A) and biofilm formation gene (Ica A) (Figure 1) in the six randomly selected strains (2 environmental, 2 animal and 2 human samples) revealed that Mec A was only detected in one environmental sample and all other animal and human samples, while Ica A was detected in all of the selected strains. Referring to genotypic detection of MRSA gene (Mec A) and biofilm formation gene (Ica A) in S. aureus strains isolated in this study, there was a correlation between the high prevalence of Mec gene, Ica gene, and biofilm formation that indicated the important role of biofilm in the pathogenesis of S. aureus. In addition, biofilm formation resulted in marked antimicrobial resistance due to the reduction of antimicrobial penetration, slower bacterial metabolic state as well as easier exchange of resistance genes among cells which complicates the therapeutic approaches against S. aureus associated infections (Arciola et al., 2001; Yazdani et al., 2006; Cosgrove and Fowler, 2008; Khameneh et al., 2016; Naicker et al. 2016).

Figure 1: Agarose gel amplification for PCR products specific for S. aureus isolates on Nuc (a), Mec A (b) and Ica A (c) genes amplified 395 bp, 310 bp and 1315 bp, respectively. Lane (L): 100 bp Ladder ‘’Marker’’, Lanes (1–6): examined samples, Lane Pos: Positive control, Lane Neg: Negative control.

CONCLUSION

In the light of the study results it can be concluded that the environment considers the link between animal and human infections with MRSA through poor standard of hygiene also animal attendants played a significant role in the circulation of the pathogen in the environment in small dairy units that considered representative to a major sector of dairy industry in Egypt with similar circumstance and facilities. Furthermore, a cross relation between antibiotic resistance, in particular, methicillin and biofilm formation was detected this was reflected by the presence of Mec and Ica A genes in the same selected isolates. Further studies should be employed to control the dissemination of such MDR, biofilm producers’ isolates of S. aureus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Professor Mohamed A. El Bably professor of Animal, Poultry and Environmental hygiene, Beni-Suef University for his valuable assistance in writing this paper and Dr. Ahmed Orabi, Department of Microbiology and Immunology Cairo University for technical help. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTeREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Authors 1 and 2: shearing the conception and design of the study acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and all the scientific writing, while author 3 drafting the manuscript and grammar revision also writing revision.

REFERENCES