Off-Farm Employment among Small Farm Holders of Different Tenurial Status in Peshawar Valley of Khyber Pakhtunkwa

Research Article

Off-Farm Employment among Small Farm Holders of Different Tenurial Status in Peshawar Valley of Khyber Pakhtunkwa

Haidar Ali, Malik Muhammad Shafi* and Himayatullah Khan

Institute of Development Studies, Faculty of Rural Social Sciences, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | The present study investigated the off-farm employment among small farm holders of different tenurial status in Peshawar Valley of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A sample of 201 farm households (Owners, Owner-cum-tenants and tenants) was selected using random sampling technique and data were collected through a pre-tested interview schedule. This study is focused on two selected districts of Peshawar and Charsadda. Four villages were studied two each from the sampled districts. Analysis showed that owners (59.31 percent off-farm employment) were performing more off-farm jobs than the tenants (50.74 percent off-farm employment) and owner-cum-tenants (41.77 percent off-farm employment). The dominancy of owners in the off-farm employment was associated to the farm holding size (up to 1 acre), they operated. Similarly the small farm households (Owners, Owner-cum-tenants and tenants) of developed villages (i.e. Dawood Zai and Rajjar) perform more off-farm employment than the small farm households (Owners, Owner-cum-tenants and tenants) of underdeveloped villages (i.e. Garhi Baghbanan and Mufti Abad). This could be associated to the developed means of transport and communications, better education facilities, market facilities as well as availability of off-farm jobs locally. The study recommends that with the decrease in the size of holdings unemployment in the agriculture sector is likely to increase. There is a need to create off-farm employment opportunities. Agro based industries seems to potential area to generate employment opportunities. Simultaneously there is need for initiating skill development programs.

Received | August 16, 2016; Accepted | September 09, 2016; Published | October 26, 2016

Correspondence | Malik Muhammad Shafi, Institute of Development Studies, Faculty of Rural Social Sciences, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkwa, Pakistan; Email: drmms@aup.edu.pk

Citation | Ali, H., Shafi, M.M., and H. Khan. 2016. Off-Farm employment among small farm holders of different tenurial status in Peshawar valley of Khyber Pakhtunkwa. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 32(4): 334-342.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2016.32.4.334.342

Keywords | Tenurial Status, Small Farm Households, Developed and Underdeveloped Villages, Dummy Variable Multiple Regression Model, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Off-farm Occupational Pattern

Introduction

In the rural areas of South Africa, land is the most important asset in primarily agrarian, but is lacking in both size and ownership. There are preventive social and administrative set up, i.e. land tenure that should be developed. Most owners, owner-cum-tenants and tenants have received inadequate or inappropriate research and extension support. They also have limited access to land and capital which have resulting in frequently low standards of living. This is because of the inefficient and unproductive use of land in the absence of appropriate extension services and research. In developing countries, agriculture is largely carried out under increasing pressure of scarce land resources managed under insecure customary land ownership and communal grazing land. These insecure tenure systems i.e. communal land tenure systems constrain the ability of small farmers to produce more from the existing land (Babatunda, 2010).

Owner, owner-cum-tenants and tenants having small land holding are under continuous pressure to increase production from their limited land resource. Thus, the sub-marginal and marginal-size farms cannot remain subsistence oriented. The income from off-farm and non-farm employment assists the owner, owner-cum-tenants and tenants of small-land holding to become or remain hunger-free. Thus, to combat rural poverty and to secure adequate livelihood for owner, owner-cum-tenants and tenants having small land holding off-farm rural employment is essential (Ali et al., 2014).

Off-farm sector is attained very little attention in Pakistan, because mainly the emphasis of rural development and poverty mitigation programs/policies is based on the development of agriculture sector. So, to evaluate and assess the rural off-farm economy a comprehensive research is required. In this respect, the present research is an effort with the goal to identify the off-farm employment among small farm holders of different tenurial status in Peshawar valley of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Materials and Methods

Peshawar Valley constitutes the study area for this research. The reason for the selection of Peshawar valley is that most of the agricultural activities are carried out in this zone. It is also worth mentioning that Peshawar valley is considered as food basket for the entire province. So the study was conducted in Peshawar Valley. Many owners, owner-cum-tenant and tenants are engaged in off-farm employments like wage labour, skilled employment and trade employment. As the Valley constitutes five districts i.e. Peshawar, Charsadda, Mardan, Nowshehra and Swabi out of which two districts i.e. Peshawar and Charsadda were selected for the present study. Because most of the farm families have small land holdings and their average size of holding is around 2.03 acre (GoP, 2014). For present study household were taken as a unit of analysis and data were collected at household level from the head of the small farm household.

Data were collected from the selected sample of small farm households using random sampling technique from the study area. Selection of villages were made on the basis of socio-economic features of these villages using purposive sampling technique. The main features required were to select villages with agricultural background but where development of infrastructure and other socio economic factors have resulted in the diversified the livelihood. Also we need to consider the backwardness and development factors [also known as external factors e.g. road infrastructure, health facilities etc.] of the villages, so that we can compare the impact of different internal factors like household size, farm size, ownership status, etc. of different villages. On this criterion, Dawood Zia, and Rajjar comparatively developed villages and Garhi Baghbanan, and Mufti Abad comparatively underdeveloped villages were selected. Dawood Zia and Rajjar having almost all type of infrastructural facilities including; transport, communication, education, health, and allied markets for various commodities. In contrast to that, Garhi Baghbanan and Mufti Abad are underdeveloped villages lacking all the major facilities mentioned above. The dominant source of livelihood is agriculture in these villages.

Sample size (20 %) was fixed due to human and financial constraints. Sample was properly divided in the above-mentioned villages through proportional allocation method. A total of 201 sample small farm households (owner, owner-cum-tenants and tenants) were taken from the total small farm household of (owner, owner-cum-tenants and tenants) 1006 and randomly selected from the above mentioned villages. As the data were collected from the farming household head, list of small farming households were obtained from the patwari of the concerned patwar circle of revenue department.

Model Selection and Specification

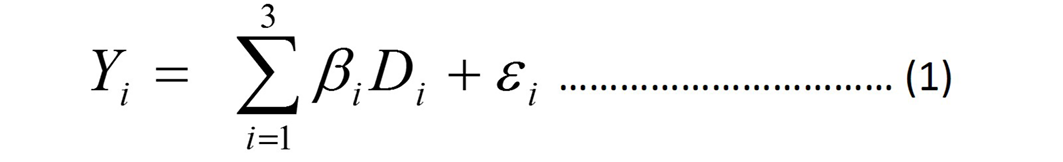

The dependent variable in regression analysis is frequently influenced not only by variable which are quantitative in nature but also qualitative. Usually such variables show the absence or presence of phenomena. For the computation of such phenomena artificial variables are constructed that takes on value of 0 or 1 showing the absence or presence of phenomena. Dummy variable can be incorporated as quantitative variables in regression models. Which are called Analysis of Variances (ANOVA) models. Khan (2007) also used a similar model for the estimation of underemployment. So, in the present study for comparison of off-farm employment among the small farm households of different tenurial status a dummy variable multiple regression model was used in which the dummy repressor (variable or agent) taking the values of 0 if the observation does not belong to a particular group and 1 if it belongs to that group. Model was used with care to avoid the dummy trap. For this purpose (m-1) dummy variables were used with an intercept or (m) without an intercept.

Comparing Off-Farm Employment among the Small Farm Households of Different Tenurial Status by Using Dummy Variable Approach

For comparing the off-farm employment on the basis of their tenurial status among the small farm households dummy variable multiple regression model was used. On the basis of their tenurial status the small farm households were divided into three categories i.e. owners, owner-cum-tenants, and tenants. Following Mecharla (2002), Khan (2007) and Ali et al. (2014), the following multiple regression model was used to analyze the effect of tenancy on off-farm employment.

Functional Form of the Above Model;

Yi = β1D1+ β1D1+ β1D1+ Ɛi …........................(2)

Whereas;

β1 to β3 = dummy coefficients

Yi = Level of off-farm employment of household i

D1i = 1 if household i is owner, 0 otherwise,

D2i = 1 if household i is owner-cum tenant, 0 otherwise,

D3i = 1 if household i is tenant, 0 otherwise,

Ɛi = Error term

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by using SPSS (Statistical Product for Social Science) 20 version and Gretl 1.9.8.

Results and Discussion

Distribution of farm size of sample small farm households is explained in Table 1. In developed (developed means of transport and communications, better education facilities, market facilities as well as availability of off-farm jobs locally) village of district Peshawar, highest (46.15%) had farm size up to 1 acres land. From the remaining, 25% had a farm size from 1.1 acre to 2 acre land, 19.23 % had a farm size from 2.1 acre to 3 acre land, 5.77 % had farm size from 3.1 acre to 4 acre land and 3.85 % had farm size above 4 acre.

Table 1: Distribution of Sample Small Farm Households According to Farm Size

| Farm Size | Percentage Distribution of Farm Size in | |||||||||

| Peshawar | Charsadda | Overall | ||||||||

| Dawood Zai | Mula Zia | Rajjar | Mufti Abad | |||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Up to 1 | 24 | 46.15 | 18 | 39.13 | 22 | 37.29 | 14 | 31.82 | 78 | 38.81 |

| 1.1-2 | 13 | 25.00 | 10 | 21.74 | 17 | 28.81 | 10 | 22.73 | 50 | 24.88 |

| 2.1-3 | 10 | 19.23 | 8 | 17.39 | 11 | 18.64 | 9 | 20.45 | 38 | 18.91 |

| 3.1-4 | 3 | 5.77 | 6 | 13.04 | 5 | 8.47 | 6 | 13.64 | 20 | 9.95 |

| Above 4 | 2 | 3.85 | 4 | 8.70 | 4 | 6.78 | 5 | 11.36 | 15 | 7.46 |

| All Farms | 52 | 100 | 46 | 100 | 59 | 100 | 44 | 100 | 201 | 100 |

Source: Field Survey, 2014

Table 2: Distribution of Sample Small Farm Households on the Basis of Ownership Status

| Tenancy Status | Percentage Distribution of Sample Small Farm Households in | |||||||||

| Peshawar | Charsadda | Overall | ||||||||

| Dawood Zai | Mula Zia | Rajjar | Mufti Abad | |||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Owners | 32 | 61.54 | 25 | 54.35 | 31 | 52.54 | 21 | 47.73 | 109 | 54.23 |

| Owners-cum-tenants | 7 | 13.46 | 10 | 21.74 | 9 | 15.25 | 11 | 25.00 | 37 | 18.41 |

| Tenants | 13 | 25 | 11 | 23.91 | 19 | 32.20 | 12 | 27.27 | 55 | 27.36 |

| All | 52 | 100 | 46 | 100 | 59 | 100 | 44 | 100 | 201 | 100 |

Source: Field Survey, 2014

Similarly in underdeveloped village of district Peshawar, majority (39.13%) was found to have a farm size up to 1 acre land. From the remaining, 21.74% was noted to have a farm size from 1.1 acre to 2 acre land, 17.39% was recorded to have a farm size from 2.1 acre to 3 acre land, 13.04% was observed to have a farm size from 3.1 acre to 4 acre land, and 8.70% was found to have a farm size above 4 acres land. Likewise, in developed village Rajjar of district Charsadda, greater part (37.29%) were operating farm size up to 1 acre. From the remaining, 28.81% had a farm size from 1.1 acre to 2 acre land, 18.64% was noted to have a farm size from 2.1 acre to 3 acre land, 8.47% had a farm size from 3.1 acre to 4 acre land, and 6.78% had a farm size above 4 acres land. Similarly, in underdeveloped village of district Charsadda, highest (31.82%) were operating farm size up to 1 acre land. From the remaining, 22.73% was observed to have a farm size from 1.1 acre to 2 acre land, 20.45% was recorded to have a farm size from 2.1 acre to 3 acre land, 13.09% had a farm size from 3.1 acre to 4 acre land, and 11.36% was found to have a farm size above 4 acres land. The small size holdings among large number of sample farm households is due to increase in population which leads to fragmentation of lands. These figures confirm the assumption that the research area was the residence of a small farm. Findings of this study are consistent with the findings of the Khan (2007), Tahir (2008) and Ali et al. (2014) who explicitly stated that majority of small farm households were working on small farms up to one acre land in their study area.

Table 2 reports the ownership status among small farm households. During the survey, it was found out that owners were highest (54.36%) in overall three districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Furthermore, in developed and underdeveloped villages of district Peshawar owners were found in majority (61.54%, 54.35%). In the same way in developed and underdeveloped villages of district Charsadda, highest 52.54% and 47.73% were owners. The dominancy of owners in developed villages may be due to easy accessibility of local markets, improved transport services, more income from farm productivity and higher educational level of the people in general. While in underdeveloped villages the owners are small in numbers may be due to less availability of local markets, low level of income from farm productivity, low level of education and insufficient transport services in those areas. All these factors could be responsible for such findings. Whereas, these results are reliable with the findings (Owners were more in developed villages because of more income from farm productivity, presence of local markets and transport services as compared to underdeveloped villages) concluded by Matshe and Trevor (2004), Babatunda (2010) and Mecharla (2002).

Farm size’s distribution through owners, owner-cum-tenants and tenants are presented below. According to Table 3, highest 64.22% owners were operating farm size up to 1 acre land followed by from 1.1 acre to 2 acres land (24.77 percent), from 2.1 acre to 3 acres land (6.42 percent), from 3.1 acre to 4 acres land (2.75 percent) and above 4 acres land (1.83 percent).

Table 3: Distribution of Farm Size of Sample Small Farm Households on the Basis of Tenurial status

| Farm Size (Acres) |

Percentage Distribution of Sampled Respondents in |

|||||||

| Owners | Owners cum tenants | Tenants | Overall | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

|

Upto 1 |

70 | 64.22 | 3 | 8.11 | 5 | 9.09 | 78 | 38.81 |

| 1.1-2 | 27 | 24.77 | 11 | 29.73 | 12 | 21.82 | 50 | 24.88 |

| 2.1-3 | 7 | 6.42 | 13 | 35.14 | 18 | 32.73 | 38 | 18.91 |

| 3.1-4 | 3 | 2.75 | 6 | 16.22 | 11 | 20.00 | 20 | 9.95 |

| Above 4 | 2 | 1.83 | 4 | 10.81 | 9 | 16.36 | 15 | 7.46 |

| All Farms | 109 | 100 | 37 | 100 | 55 | 100 | 201 | 100 |

Source: Field Survey, 2014

Similarly, majority (35.14%) owner-cum-tenants had landholding from 2.1 acre to 3 acres land followed by from 1.1 acre to 2 acres land (29.73%), from 3.1 acre to 4 acres land (16.22%), above 4 acres (10.81%) and up to 1 acre (8.11%). Likewise, greater part (32.73%) were operating farm size from 2.1 acre to 3 acres land followed by from 1.1 acre to 2 acres land (21.82%), from 3.1 acres to 4 acres (20 percent) above 4 acres (16.36 percent), up to 1 acre (9.09 percent) and from 1.1 acre to 2 acres land (7.79 percent).These results illustrate that greater part of owner were operating small farms up to 1 acre in contrast to owner-cum-tenants and tenants, which were operating reasonably large farms. These findings are consistent with the findings derived by Mecharla (2002), Zahid (2006) and Man and Sadiya (2009). Who reported that owners had small landholding size as compared to owner-cum-tenants and tenants.

Table 4: Area Operated by Different Tenurial Classes of Small Farm Households in Acre

| Tenancy Status | Area Operated by Different Tenurial Classes in | |||||||||

| Peshawar | Charsadda |

Overall |

||||||||

| Dawood Zai | Mula Zia | Rajjar | Mufti Abad | |||||||

| Area | % | Area | % | Area | % | Area | % | Area | % | |

| Owners | 49.13 | 37.56 | 54.52 | 54.29 | 59.63 | 35.64 | 51.11 | 51.70 | 214.39 | 43.10 |

| Owners-cum-tenants | 30.43 | 23.26 | 12.19 | 12.14 | 34.31 | 20.50 | 19.49 | 19.71 | 96.42 | 19.38 |

| Tenants | 51.24 | 39.17 | 33.72 | 33.58 | 73.39 | 43.86 | 28.26 | 28.59 | 186.61 | 37.52 |

| All Farms | 130.80 | 100 | 100.43 | 100 | 167.33 | 100 | 98.86 | 100 | 497.42 | 100 |

Source: Field Survey, 2014

Table 5: Off-farm Occupational Status of Sample Small Farm Households

| Types | Percentage Off-farm Occupational Pattern in | |||||||||

| Peshawar | Charsadda | Overall | ||||||||

| Dawood Zai | Mula Zia | Rajjar | Mufti Abad | |||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Permanent Employees | 11 | 21.15 | 7 | 15.22 | 15 | 25.42 | 8 | 18.18 | 41 | 20.40 |

| Trade and Commerce | 18 | 34.62 | 14 | 30.43 | 20 | 33.90 | 17 | 38.64 | 69 | 34.33 |

| Daily Paid Labors | 23 | 44.23 | 25 | 54.35 | 24 | 40.68 | 19 | 43.18 | 91 | 45.27 |

| All | 52 | 100 | 46 | 100 | 59 | 100 | 44 | 100 | 201 | 100 |

Source: Field Survey, 2014

Table 4 illustrates the total area operated by different tenurial classes (owners, owner-cum-tenants and tenants) of small farm households in the study area. In developed village of district Peshawar, 52 small farm households possessed a total of 136.19 acres. Out of this, highest 54.52 acres (40.03%) was owned by owners followed by tenants 51.24 acres (37.62%) and owner-cum-tenants 30.43 acres (22.34%). Similarly, in underdeveloped village of district Peshawar, 46 small farm households having a total of 95.04 acres. In which, greater part 49.13 acres (51.70%) was related to owners followed by tenants 33.72 acres (35.48%) and owner-cum-tenants 12.19 acres (12.83 %). Likewise, in developed village of district Charsadda, 59 small farm households were holding a total of 167.33 acres. Greater part 73.39 acres (43.86%) was belonged to tenants followed by owners 59.63 acres (35.64%) and owner-cum-tenants 34.31 acres (20.50 percent).Correspondingly, in underdeveloped village of district Charsadda, 44 small farm households possessed a total of 98.86 acres. Out of this, highest 51.11 acres (51.70%) belonged to owners followed by tenants 28.26 acres (28.59%) and owner-cum-tenants 19.49 acres (19.71 percent).

Table 5 describes off-farm occupational pattern in each district and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Permanent employee (government), Trade and commerce (business activities) and daily paid jobs are commonly found in off-farm in the research area. In developed village of district Peshawar, majority (44.23%) were engaged in daily paid labours followed by (34.62%) trade and commerce and (21.15%) permanent employee. Similarly in underdeveloped village of district Peshawar, maximum (54.35%) were found to be daily paid labours. From the remaining (30.43%) were belonged to trade and commerce followed by (15.22%) permanent employee. Likewise in developed village of district Charsadda, highest (40.68%) were involved in daily paid labours followed by (33.90%) trade and commerce and (25.42%) permanent employee. In the same way in underdeveloped village of district Charsadda, uppermost (43.18%) were daily paid labour followed by (38.64%) trade and commerce and (18.18%) permanent employee. The above facts and results reveal that greater part of small farm households (owners, owner-cum-tenants and tenants) operating small farm land were performing off-farm employment to expand their income sources. Because of low educational level amongst the small farm households, daily paid labors and trade and commerce (livestock merchant, timber associated business and shopkeeper) jobs of casual nature were the main occupations

Table 6: Time Spent of Different Tenurial Classes (Owner, Owner-cum-tenants and Tenants) on Off-farm Employment

| Tenure Status |

Time Spent of Tenurial Classes (Owner, Owner-cum-tenants and Tenants) on Off-farm Employment |

||||

| Peshawar | Charsadda | Overall | |||

| Dawood Zai | Mula Zia | Rajjar | Mufti Abad | ||

|

Time Spent/day (Hours) |

Time Spent/day (Hours) |

Time Spent/day (Hours) |

Time Spent/day (Hours) |

Time Spent/day (Hours) |

|

| Owners | 16.50 | 11.70 | 13.94 | 10.40 | 13.14 |

| Owners-cum-tenants | 8.10 | 6.00 | 5.10 | 3.00 | 5.55 |

| Tenants | 11.84 | 8.74 | 9.16 | 7.06 | 9.20 |

| All Farms | 12.15 | 8.81 | 9.40 | 6.82 | 9.30 |

Source: Field Survey, 2014

of small farm householders in developed and underdeveloped villages. The findings of the current study are in line with the findings of Zahid (2006), Tahir (2008) and Ali and Shafi (2012).

Table 6 illustrates time spent per week by different tenurial classes (owners, owner-cum-tenants and tenants) among small farm households on off-farm employment in overall two districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Furthermore in developed village of district Peshawar, average working hours consumed per week on off-farm employment by different tenurial classes was 12.15 ranging from 8.10 to 16.50 hours. Highest (16.50) average working hours per week on off-farm employment was observed among owners followed by tenants (11.84 hours) and owner-cum-tenants (8.10 hours) in developed village of district Peshawar. Similarly in underdeveloped village of district Peshawar, average working hours spent per week on off-farm employment by different tenurial classes was 11.70 ranging from 8.74 to 11.70 hours. Highest (11.70) average working hours per week on off-farm employment was observed among owners followed by tenants (8.74 hours) and owner-cum-tenants (6.00 hours) in underdeveloped village of district Peshawar. Likewise in developed village of district Charsadda, average working hours used up per week on off-farm employment by different tenurial classes was 9.40 ranging from 9.16 to 13.94 hours. Highest (13.94) average working hours per week on off-farm employment was found among owners followed by tenants (9.16 hours) and owner-cum-tenants (5.10 hours) in developed village of district Charsadda. Similarly, in underdeveloped village of district Charsadda, average working hours spent per week on off-farm employment by different tenurial classes was 6.82 ranging from 7.06 to 10.40 hours. Highest (10.40) average working hours used up per week on off-farm employment was found among owners followed by tenants (7.06 hours) and owner-cum-tenants (3.00 hours) in underdeveloped village of district Charsadda. Working hours consumed per week on off-farm employment was more among owners than owner-cum-tenants and tenants in overall two districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. It may be owners operating less farm size in overall two districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Due to which, more family labours would be engage in off-farm employment. On other hand owner-cum-tenants and tenants may be operating more farm size in overall two districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Due to which more family labors would be engage in different farming activities. These results are in line with the findings of Man and Sadiya (2009), Velazco (2002), Khan (2007) and Vijay (2011), who reported that off-farm employment was found more among owners.

Table 7: Comparing Off-farm Employment among Small Farm Households of Different Tenurial Status by Using Dummy Variable Approach

| Variables | Coefficients | Std. Error | t-ratio | P-value |

|

D1(Owners) |

60.148 | 2.005 | 29.999 | .000* |

|

D2 (Owner cum tenants) |

30.680 | 1.809 | 16.960 | .000* |

|

D3(Tenants) |

42.523 | 1.579 | 26.930 | .000* |

*Highly Significant R-squared: 0.6331; Adjusted R-squared: 0.620; F-statistic: 154.810; P-value (F): .000

Table 7 shows the results of dummy variable multiple regression model of tenurial status. The model is overall significant because the F-statistic is highly significant. Individual result of each variable is very much significant as indicated by the value of t-ratio and can be accepted at 95%confidence level. Regression results show that the slop coefficients of D1, D2 and D3 are statistically significant as p-values of the respective coefficient are quite low. Therefore, the comparison of tenurial status is made on the basis of their slop coefficients. The average level of off-farm employment of those who are owners is 60.14 % followed by 42.52 % tenants and 30.68 % owner-cum-tenants. There is significant difference among off-farm employment level of tenurial status as indicated by their coefficients. Owners perform more off-farm employment than owner-cum-tenants and tenants as indicated by the large value of slop coefficient D1. Typically, it is believed that owners perform less off-farm because of their high farm income and tenants perform more off-farm, as they have to pay half of their farm income as rent. After having in depth enquiry of the data it was found that the majority of the owners were operating small farms up to 1 acre in overall three districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Due to which more family labors would be engage in off-farm employment. On the other hand, owner-cum-tenants and tenants may be operating more farm size in overall three districts and their respective developed and underdeveloped villages. Due to which more family labors would be required to engage in different farming activities. These results are in line with the findings of Velazco (2002), Man and Sadiya (2009), Babatunda and Olagunju (2010) and Vijay (2011), reported that off-farm employment was found more among owners.

Conclusions

Agriculture is the major source of employment in Peshawar Valley. Most of the people engaged in agriculture profession. Due to small size of holdings, off-farm employment was a common phenomenon in the agriculture sector. On average, owners perform more off-farm work followed by owners-cum-tenants and tenants. In the off-farm employment the dominancy of owners were related to the farm size holding, they operated. It was also observed that the owners of Dawood Zai and Rajjar comparatively developed villages perform more off-farm jobs than back ward villages (Mula Zai and Mufti Abad). It may be due to the availability of more off-farm jobs (daily wages, govt. jobs, part time employment and small business activities) and easy accessibility to local markets in developed villages as compared to underdeveloped villages. Most of the small farm households (owners, owner-cum-tenants and tenants) sell their labors services for wage and salary because business is out of their reach due to lack of capital and skill.

Recommendations

On the basis of the research study, following recommendations are suggested.

- 1. Level of off-farm employment is negatively related with the farm size (Ali et al., 2014). Farm size is likely to decrease overtimes due to the law of inheritance. There is a need to generate off-farm employment opportunities (tailoring, retailers, wholesalers, transport operators, and private entrepreneurs etc.) through public and private partnership.

- 2. Government should make policies to stop marginalization so that the division of agriculture land should be up to a certain limit from which the farm households could be able to earn their livelihoods.

- 3. The capacity of agriculture as well as livestock sectors while absorbing agriculture labors is limited. It is primordial for policy makers to look towards processing activities and value added products in the field of agriculture. It will create job opportunities in the rural areas.

- 4. We have manpower along with talent. There is a need to open skill development centres in the rural areas to impart training and skills to the professions such as bee keeping, welding, electrification works and handicraft activities etc.

Authors’ Contribution

Haidar Ali has done work in collection of data, writing of results and discussion. Dr. Malik Muhammad Shafi has helped in checking the manuscript, and Dr. Himayatullah helped in econometric analysis.

References

Ali, H., M. M. Shafi. 2012. Determinants of off-farm employment among small farm holders in Peshawar Valley of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. S. J. Agric. 27(1): 15-20.

Babatunda, R.O. 2010. Determinants of participation in off-farm employment among small-holder farming households in Kwara State, Nigeria. J. Ext. Rural Dev. 6(2): 1-14.

Babatunda, R.O., and F.I. Olagunju (2010). Off-farm and on farm employment decisions among small farm households in Nigeria. J. Agric. Eco. 30 (3): l75-l86.

Bezemer, D.J., and J. Davis. 2003. The rural non-farm economy in Romania. J. Agric. Econ. 53(3):378-392.

Bojnee, S., and L. Dries. 2005. Causes of changes in agricultural employment in Slovenia evidence from micro-data. J. Agric. Econ. 56(4):399-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2005.00020.x

Ellis, F. 2000. Determinants of rural livelihood diversification in developing countries. J. Agric. Econ. 51(2):289-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2000.tb01229.x

Ministry of Finance. 2014. Economic Survey of Pakistan 2013-14. Finance and Economic Affairs Division, Ministry of Finance, Govt. of Pakistan, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Haggablade, S., H. Peter and T. Reardon. 2002. Strategies for stimulating poverty-alleviating growth in the rural non-farm economy in developing countries. Issue 92. Enviro. & Prod. Technical. Dev. World Bank. Rural Dev. Department Discussion Paper.

Hardaker, J.B., and M.F. Robzen. 2002. Making agricultural diversification work for the poor; the challenge for the Asia-Pacific region. UN-FAO CUREMIS workshop 30-31 May, 2002. University of Bangkok, Bangkok, Thailand.

Hazell, P., S. Haggablade and T. Reardon. 2002. The rural non-farm economy pathways, way out of poverty or pathway in Michigan State University, USA.

Lanjouw, P., and A. Sharif. 2002. Rural non-farm employment in India, access income and poverty impact. Working paper No. 81, United Nations Development Program, National Council of Applied Economics Research, India.

Lewis, W.A. 1954. Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies. 22 (4):139-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.1954.tb00021.x

Janowski, M., and A. Bleahu. 2001. Factors affecting household level involvement in rural off-farm economic activities in two communities in Dolj and Brasov Judete, Romania, Paper presented at the workshop “Rural off-farm employment and development in transition economies”, University of Greenwich, London.

Kimhi, A., and R. Eliel. 2004. Time allocation between farm and off-farm activities in Israeli farm households. American J. Agric. Econ. 86(3):716-721. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0002-9092.2004.00613.x

Kuhnen, F. 1989. Rural household survival strategies in the third world. Institute for Rural Entwicklung, Universitat Gottingen, and Busgenweg 2, 3400 Gottingen, German Federal Republic. 23(5):33-41.

Matshe, M., and Y. Trevor. 2004. Off-farm labor allocation decisions in small- scale rural households in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Agric. Eco. 30(3):l75-l86.

Mecharla, P.R. 2002. The determinants of rural off-farm employment in two villages of Andhra Pradesh, India.Working Paper No. 12, Poverty Research Unit at Sussex University of Sussex Falmer, Brighton, United Kingdom.

Monica, J. 2003. Rural off-farm livelihood activities in Romania, Georgia and Armenia: synthesis of findings from fieldwork carried out at village level 2001—2002.

Man, N., and S.I. Sadiya. 2009. Off-farm employment participation among paddy farmers in the Muda Agricultural Development Authority and Kemasin Semerak Granary areas of Malaysia. J. Agric. Econ. 16(2):34-42.

Siphambe, H.K. 2003. Understanding unemployment in Botswana. South African J. Econ. 71(3):200-230.

Tahir, M. 2008. Factors determining off-farm employment amongst small farmers. Sarhad J. Agric. 28(1):13-20.

Thakur, S.C.P., A.K. Chaudhary and R.K.P. Singh 1993. Employment and labour productivity in developed and under-developed agricultural regions in Bihar. J. Manpower. 29(2):25-36.

Velazco, J. 2002. Non-farm rural activities (NFRA) in a peasant economy: The case of the North Peruvian Sierra. Paper presented at the 2nd EUDN Workshop on Development Research for doctoral students, Bonn.

Vijay, M., and R.K. Gupta. 2011. Non-farm opportunities for smallholder agriculture. Conference on new directions for smallholder agriculture 24-25 January 2011, Rome, IFAD HQ.

Vijay, M., and R.K. Gupta. 2014. Off-farm opportunities for small farm householder agriculture. Conference on new directions for smallholder agriculture 24-25 January 2014, Rome, IFAD HQ.

Zahid, M.A. 2006. Determinants of off-farm-income in the mixed cropping zone of Punjab, Pakistan, M. Sc. (Hons) Thesis, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan. Pp. 46-74.